When a young priest performs an exorcism in the cold open of “The Exorcism of God,” there’s a fine line between pleasure and pain. Sometimes feeling like a Cliff Notes version of William Friedkin’s 1973 masterpiece, “The Exorcist,” the movie draws on the audience’s foreknowledge and expectations to craft its story. In the middle of the night, Father Peter Williams (Will Beinbrink) is led to a house where a young woman, Esperanza (María Gabriela de Faría), is strapped to a bed. Drenched in sweat and dirt, the woman pulsates with chaotic sexual energy. When he throws holy water on her, she arches her back. Her physicality beckons him to sin against all judgement, against all reason.

After this pivotal scene, the movie flashes forward 18 years later, and Father Peter Williams still lives in Mexico where he continues his humanitarian work. His flock considers him saintly, perhaps even magical. The Vatican treats him as a shining star, the future of the Church. He harbors a dark shadow, and the exorcism that built his reputation haunts him. As a demonic sickness spreads through the village, claiming the lives of young children, he’s drawn back into the realm of devils and demons.

There’s no doubt from the opening of this earnest film from director/co-writer Alejandro Hidalgo that we’re operating within the realm of high stakes melodrama. The film’s gothic and inky black and white cinematography lead us away from naturalist framing as the true, terrible events of that first night are slowly peeled back, revealing an unforgivable crime. Rather solemn and humorless, Father Peter Williams goes above and beyond to undo his sin. He fears that the devil that possessed him that night might still be percolating in his subconscious mind. At night, he’s haunted by terrible visions, including a sunken and bruised Jesus, who terrorizes his nightmares.

The nightmares become more intense as Father Peter is gripped with more and more doubt. A mysterious possessed woman, Silvia (Raquel Rojas) seems to be the source of the unknown illness plaguing the town. Father Peter, reluctantly, believes she needs an exorcism. Here, he enlists an old friend, Father Michael Lewis (a delightful Joseph Marcell), as he doesn’t trust himself to perform the deed on his own.

The film picks up once Father Michael arrives as the somber tone is injected with more comedy. While many (if not most) of the actors are pretty wooden, Joseph Marcell embraces the film’s spirit with gumption. Every line read is a delight, and he pulls off the high camp of off-handed one-liners like “Mescal, the best holy water I’ve had in a while,” and more serious scenes with the same commitment. More than anyone else, he seems to capture the intended ethos of the film: part inquisition into the nature of temptation, part mawkish theatrics.

Much of the movie’s second half occurs within a prison, where the possessed woman wreaks havoc. In a complete disregard for ethics, the local doctor drugs all the prisoners to protect them from “themselves and others.” We see flagrant abuses of power and authority, particularly as Father Michael begins to insist that to perform an exorcism correctly, a priest can’t just invoke God; he has to believe he is one. The walls between monsters and saviors begin to collapse completely. The subtext of these scenes exposes the corruption of institutions like The Church that take on unearned moral authority when they’re also gripped by wrongdoing.

As Father Peter grapples with doubt and questions of moral goodness, he wonders if one terrible sin can outdo all the good he’s done in the world. Peter’s guilty of far more than just lust, as his sin and later possession pull him to commit sexual assault and an even worse, unspeakable crime. On a more fundamental level, though, the screenplay does a relatively good job at outlining the true nature of sin as understood by the Church: that human pleasures only take on the burden of sin when our passion for them outsizes our love of God. The Church cares less about reducing harm than it does upholding its power. The pain that Father Peter causes will always be secondary to the damage his downfall may cause the Church. It’s easier to do a cover-up than to demand any kind of justice.

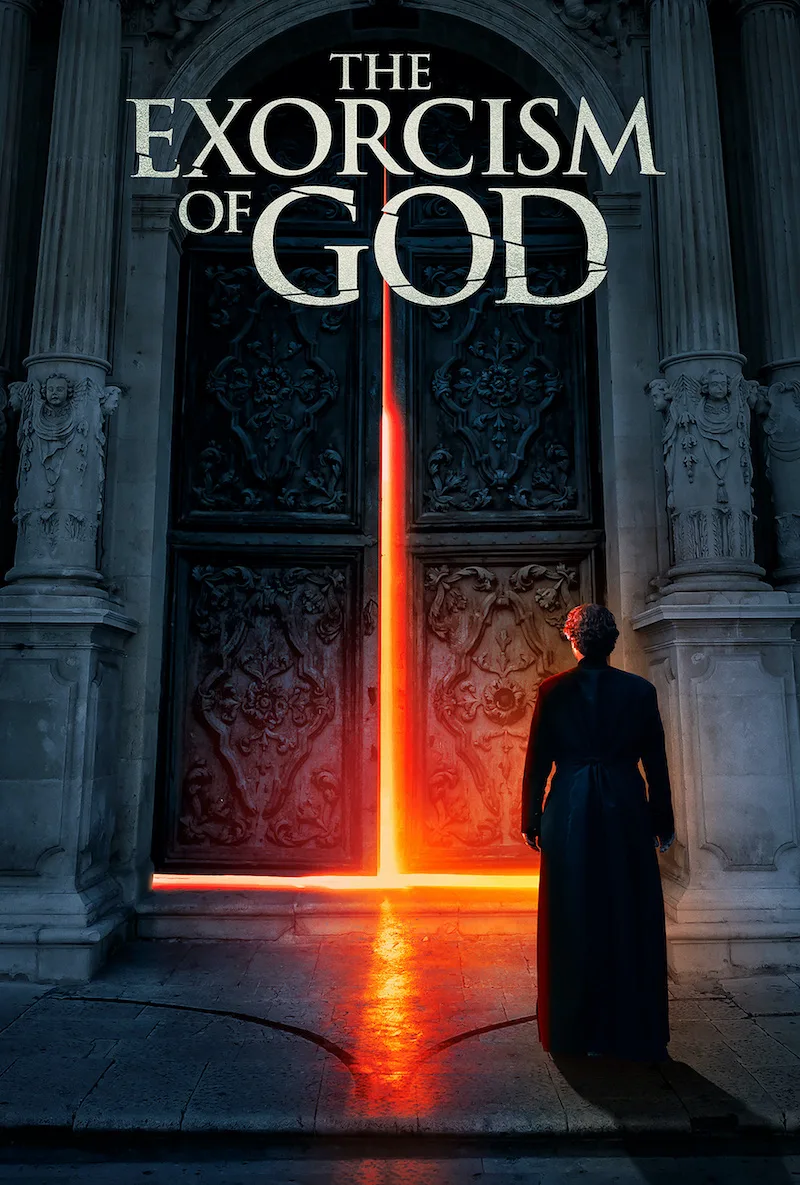

“The Exorcism of God” indulges in many aesthetic and narrative cliches as it reaches a very literal climax, but it overall features more than enough flourishes of originality to elevate it above most possession films. Its characters and narratives are well thought-out and progress logically, without significantly deviating from their goals and themes. The sound design is rapturous, and when they aren’t too dark, its images can be pretty striking. Even when it missteps on occasion, “The Exorcism of God” is always committed, and often surprising.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms.