It once was said that the cod were so populous off the coast of Nova Scotia that you could walk on the sea on their backs. Now they have virtually disappeared. The cod, the “fish” in “fish and chips,” has been overfished to near extinction. Other fish species are following.

There is heartfelt footage in “The End of the Line,” circa 1992, of angry, panicked fishermen besieging a hearing room where a government minister is calling for a moratorium on cod fishing. Brian Mulroney, Canada’s prime minister at the time, declares it a necessity. These fishermen have depended on the cod for a living, and in many cases so have their fathers back for many generations. The Canadian maritime provinces were largely settled because of the fishing industry.

A moratorium was imposed. But in 1992, it was already too late. The cod did not come back. They are virtually gone from those waters. Many documentaries about the ecology issue dire warnings of crises that will strike at some point in the future. Opponents of these films scoff at them. But “End of the Line” in large part is about what has already irrefutably happened.

Factory fishing grew too quickly, unsupervised, and damaged some fish populations so severely that their very sustainability was put into question. Giant trawlers prowled the seas halfway around the world from their ports. They used technology such as sonar to pinpoint schools of fish and bottom trawling to capture great masses of them, while incidentally wreaking havoc on the seabed.

Some nations continue to outlaw such methods. Japan continues its whaling in the face of international opprobrium. The role of other nations has been more subtle. International fishery experts were puzzled, for example, by the paradox that regional catches were down everywhere but the global catch remained steady.

How could this be? It appeared that all nations posted loses, except China, which had steady gains. Were the Chinese overfishing? Just the contrary: Scientists discovered they were making up their numbers, as regional party officials supplied fake growth statistics to look better in Beijing.

“The End of the Line” documents what threatens to become an irreversible decline in aquatic populations within 40 years. Opportunist species move in to take advantage. Oddly, the disappearance of cod has resulted in an explosion of lobsters, as they lose their chief rival for food.

There are some bright spots. The state of Alaska, for example, is praised for its fishing policies, which restrict fishing waters, the number of boats, the length of the season and the size of the catch. These policies contribute to “sustainable populations.” Wal-Mart, which sells enormous quantities of fish, is switching to sustainable sources. Ninety percent of the fish used in McDonald’s fish sandwiches is from sustainable sources.

For every bright spot, there is an omen. Fish farms, for example, seem like progress, but their fish are fed the ground-up bodies of captured free-range fish. It takes five kilos of anchovies to produce one of salmon. Bluefin tuna is an endangered species. A lot of retail tuna is not tuna at all. Some of it is dolphin, itself a threatened species.

Nobu, the famous chain of sushi restaurants, declines to remove bluefin from its menu, but promises to add a consumer advisory, comparing the situation to the health warnings on cigarettes. Not precisely a parallel: Eating bluefin is dangerous to their health, not ours.

The question arises: If fish are threatened, and beef production requires much more land and crop consumption than justified in terms of feeding the earth’s population, what are we to eat? The answer is staring us in the face: We should eat a more largely vegetarian diet, using animal proteins as humans have traditionally used them, as a supplement, rather than a main course.

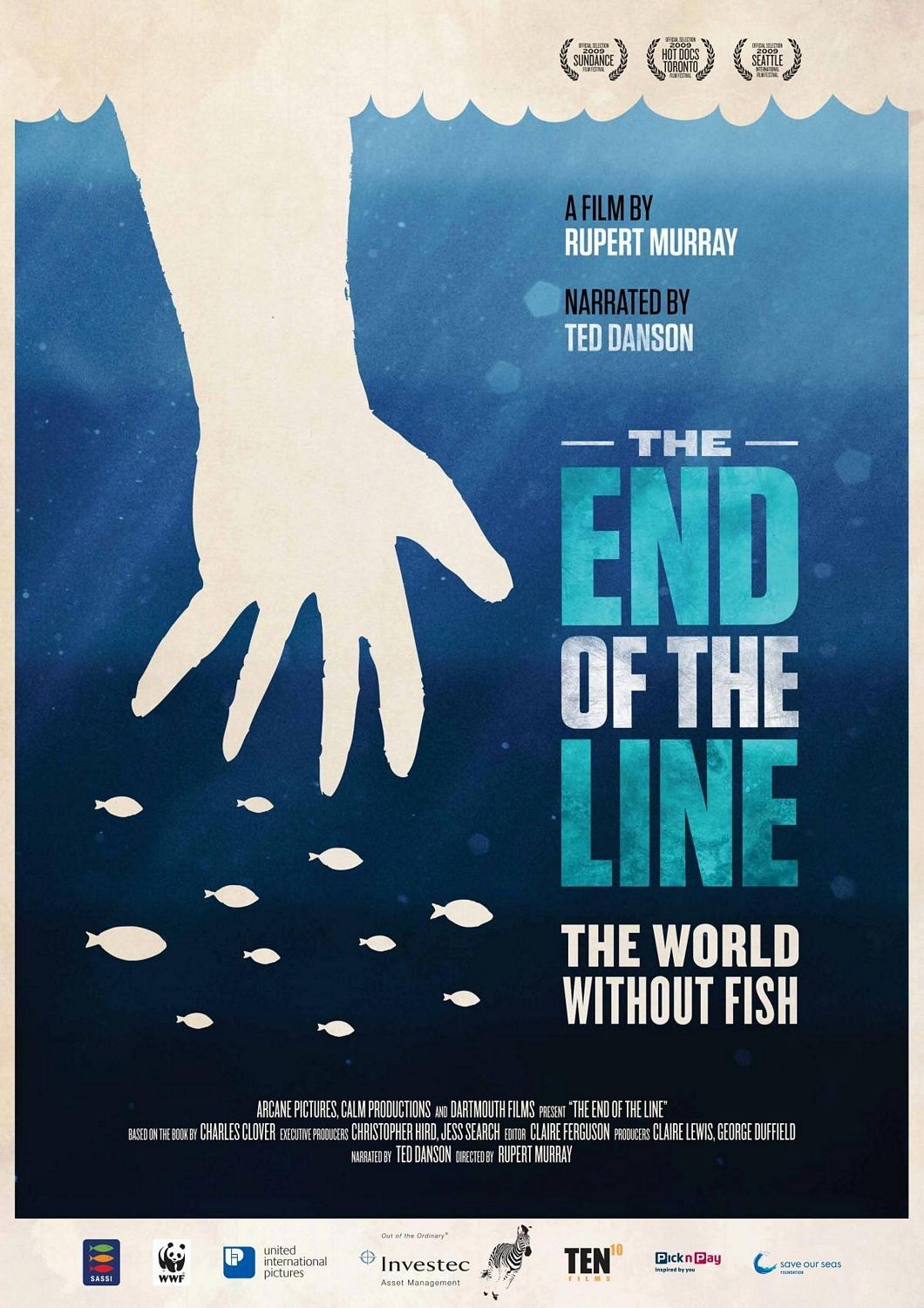

“The End of the Line,” directed by Rupert Murray, based on a book by Charles Clover, is constructed from interviews with many experts, a good deal of historical footage, and much incredible footage from under the sea, including breathtaking vistas of sea preserves, where the diversity of species can be seen to grow annually. We once thought of the sea as limitless bounty. I think I may even have heard that in school. But those fantasies are over.