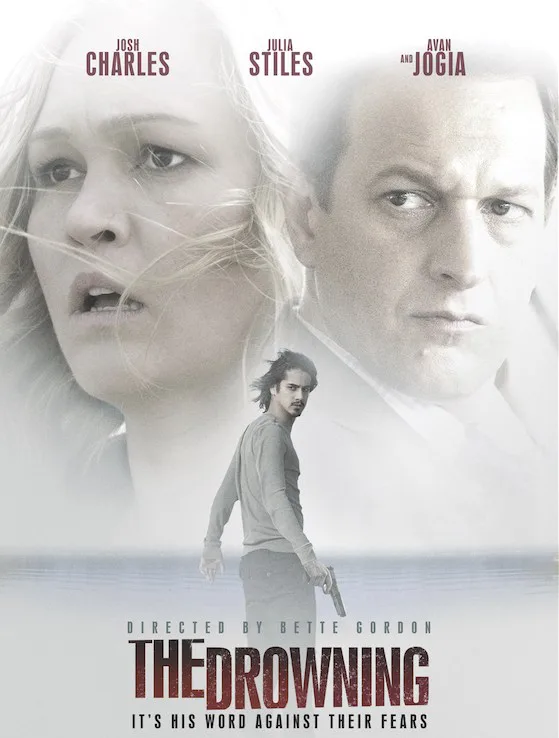

Bad pulp fiction turns readers into what Alfred Hitchcock called “the plausibles,” viewers who pick apart a work of (usually) pop art simply because it does not hew closely enough to their idea of what real life is like. I became a plausible as I watched “The Drowning,” a frustrating mystery and airport-thriller-grade psychological potboiler about psychiatrist Tom Seymour (Josh Charles). Tom tries to treat generically creepy young man Danny Miller (Avan Jogia), a former patient who (probably) committed a murder when he was only 11 years old.

Based on a novel by Pat Barker, “The Drowning” features some of the most gruel-thin justifications for its already flimsy plot machinations. It’s an obnoxious story about revenge and self-destruction that throws together a bunch of hackneyed observations about humanity, and then justifies its laziness by asking us to embrace Tom’s unbelievably forgiving artist wife Lauren (Julia Stiles) when she opines that people behave irrationally because they are “not bad,” but rather “not easy.” I wanted to pull the little hair I have left out when Lauren delivers this pseudo-sophisticated truism.

Let’s start at the top: I became a plausible while watching “The Drowning” as soon as Tom agreed to take Danny’s case. By this point, the incident from the film’s title has already occurred: Tom saves an unknown young man from drowning, only to discover that he rescued Danny. This coincidence isn’t that ridiculous when you realize that Danny is obsessed with Tom. But here’s where things get unbelievable: despite the fact that Danny tells Tom point-blank that he blames him for delivering a professional opinion that led to Danny’s incarceration in a facility for juvenile offenders, Tom gives in to pressure from fellow head-shrinker Angela (Tracie Thoms), and soon accepts Danny as one of his patients. Tom doesn’t break off contact with Danny after he shows up at his house, and casually makes friends with Lauren. Heck, Tom doesn’t even tell Lauren who Danny really is: she just knows Danny as the nice young man that her emotionally distant, but well-meaning husband saved from drowning.

At this point, I didn’t say “How does this make sense?” Instead, I went straight for “You have got to be kidding me.” Oh, sure, characters attempts to address the inherent ridiculousness of Tom’s pseudo-soul-searching quest to forgive himself by better understanding Danny. Thoms even delivers a horrendously weak line that’s meant to assuage viewers who are asking themselves “Why would Tom agree to be this kid’s confessor if he himself isn’t sure of the kid’s moral character?” She says “Like it or not, you’re in this too.” This is the kind of sentence that is only sensible in the world of “Law & Order” spin-offs and James Patterson novels. It’s about as bad as the time when Tom, supposedly shaken by the accusations of his more level-headed peers, begs off by saying “I don’t know. I don’t know what I think.”

Which is not to say that real people don’t contort themselves into positions they’ve become familiar with from pre-existing fiction. On the contrary, Jogia’s tic-riddled character and performance is proof that sometimes, people prefer cliched mannerisms to psychological realism. Jogia often talks like Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese’s “Cape Fear,” or any number of post-Hannibal Lecter psychopathic killers. He speechifies eloquently with a pseudo-probing, pseudo-knowing familiarity that’s supposed to keep you wondering where exactly he’s going. This, again, is partly the writers’, and not the performer’s, fault. But when you have a performer whose one job is to constantly pop up like a sulky Jack-in-the-box, and inexplicably get closer and closer to Tom without any plausible reason? That’s when you too will become a plausible, and stop seeing the performer as a victim of youthful bad decisions, and even worse direction, and start seeing him as a punching bag for all of your frustrations.

The film’s narrative leads Tom to pretty much exactly where you should expect it to, and climaxes with an act of violence whose sole reason-to-be is to provide a shocking source of relief for anxious viewers ostensibly hoping that Tom would stop treating Danny like a problem to solve. Director Bette Gordon (“Variety,” “Handsome Harry”) tries to lend some personality to the film’s proceedings by shooting many scenes with an attention to silhouettes, and blurry objects that seem to disappear around the periphery of Gordon’s camera frame. Viewers who dig what the filmmakers are selling might leave the film feeling like they’ve seen Tom evaporate, just like the central visual motif of raindrops on a car windshield that Gordon favors so much (she gratuitously interrupts a handful of scenes just to highlight this recurring image). But the problem with “The Drowning” isn’t that the characters are insubstantial, but rather that they don’t dry up and disappear fast enough.