“The Day I Became a Woman” links together three stories from Iran–the three ages of women–involving a girl on the edge of adolescence, a wife determined not to be ruled by her husband and a wealthy widow who declares, “Whatever I never had, I will buy for myself now.” All three of the stories are told in direct and simple terms. They’re so lacking in the psychological clutter of Western movies that at first we think they must be fables or allegories. And so they may be, but they are also perfectly plausible. Few things on the screen could not occur in everyday life. It is just that we’re not used to seeing so much of the rest of everyday life left out.

The first story is about Have, a girl on her ninth birthday. As a child she has played freely with her best friend, a boy. But on this day she must begin to wear the chador, the garment that protects her head and body from the sight of men. And she can no longer play with boys. Her transition to womanhood is scheduled for dawn, but her mother and grandmother give her a reprieve, until noon. They put an upright stick in the ground and tell her that when its shadow disappears, her girlhood is over. She measures the shadow with her fingers, and shares a lollipop with her playmate.

The second episode begins with an image that first seems surrealistic, but has a pragmatic explanation. A group of women, all cloaked from head to toe in black, furiously pedal their bicycles down a road next to the sea. A ferocious man on horseback pursues one of the women, Ahoo, who is in the lead. This is a women’s bicycle race, and Ahoo’s husband does not want her to participate. He shouts at her, at first with solicitude (she should not pedal with her bad leg) and then with threats (a bike is “the devil’s mount,” and he will divorce her). She pedals on as the husband is joined by other family members, who finally stop her forcibly.

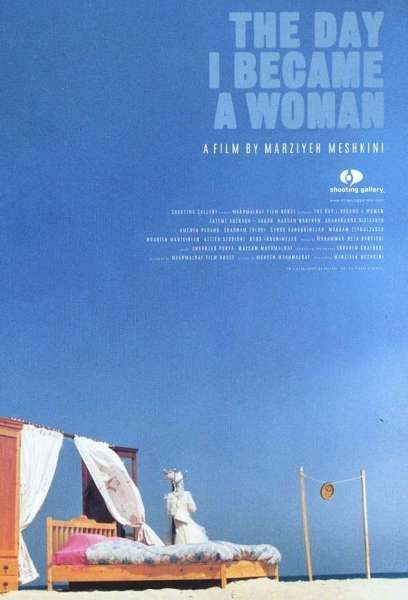

The third story begins like an episode from a silent comedy, as a young boy pushes a wheelchair containing an old woman, who is alert as a bird. She directs him into stories where she buys things–a refrigerator, a TV, tables and chairs–and soon she is at the head of a parade of boys pushing carts filled with consumer goods. We learn she inherited a lot of money and plans to spend it while she can, on all the things she couldn’t buy while she was married. The scene concludes with a Felliniesque image I will not spoil for you; it is the film’s one excursion out of the plausible and into the fantastic, but the story earns it.

“The Day I Became a Woman” is still more evidence of how healthy and alive the Iranian cinema is, even in a society we think of as closed. It was directed by Marzieh Meshkini, and produced and written by her husband, Mohsen Makhmalbaf (whose own “Gabbeh,” from 1996, found a story in the tapestry of a rug). It is a filmmaking family. Their daughter Samira directed “The Apple” in 1998, and last year her “Blackboards” was an official selection at Cannes (not bad for a 20-year-old). Unlike the heroines of this film, the women of the Makhmalbaf family can think about the day they became directors. In fact, Iranian women have a good deal more personal freedom than the women of many other Islamic countries; the most dramatic contrast is with Afghanistan.

One of the strengths of this film is that it never pauses to explain, and the characters never have speeches to defend or justify themselves (the wife in the middle story just pedals harder). The little girl will miss her playmate, but trusts her mother and grandmother that she must, as they have, modestly shield herself from men who are not family members. Only the old grandmother, triumphantly heading her procession, seems free of the system–although she, too, has a habit of pulling her shawl forward over her head, long after any man could be seduced by her beauty; the gesture is like a reminder to herself that she is a woman and must play by the rules.

This is the latest in the current Shooting Gallery series showcasing art films, and will play for two weeks.