When it comes to pioneers of modern choreography, most are familiar with Isadora Duncan. The American-born dancer, who embodied Greek ideals and a bohemian lifestyle, was memorably portrayed by an Oscar-nominated Vanessa Redgrave in the 1968 biopic, “Isadora.” She would die in 1927 after one of her signature scarves caught in the wheel spokes of an open-air car and caused her to be ejected. That tragic variation of being hung by one’s own petard helped to solidify her status as a terpsichorean legend.

But the name Loie Fuller, the subject of “The Dancer” who was an early supporter of Duncan, did not ring a bell—at least, for me. Born Mary-Louise in 1862, she was a Chicago-area native and innovator of a brand of free-form performance art known as Serpentine Dance. Her act consisted of a costume designed from massive swatches of silk attached to long bamboo rods being whirled and twirled while Fuller circled about on an elevated stage. She also invented multi-hued dramatic lighting techniques, many now commonplace, to enhance the undulations of her voluminous fabric.

However, after checking out the famous Art Nouveau posters by Jules Cheret that stylized Fuller’s allure and then realizing that the silent-era filmmakers the Lumiere brothers had featured Fuller copycats in their work, I discovered I did know of the existence of the so-called “La Danseuse de la Belle Epoque.”

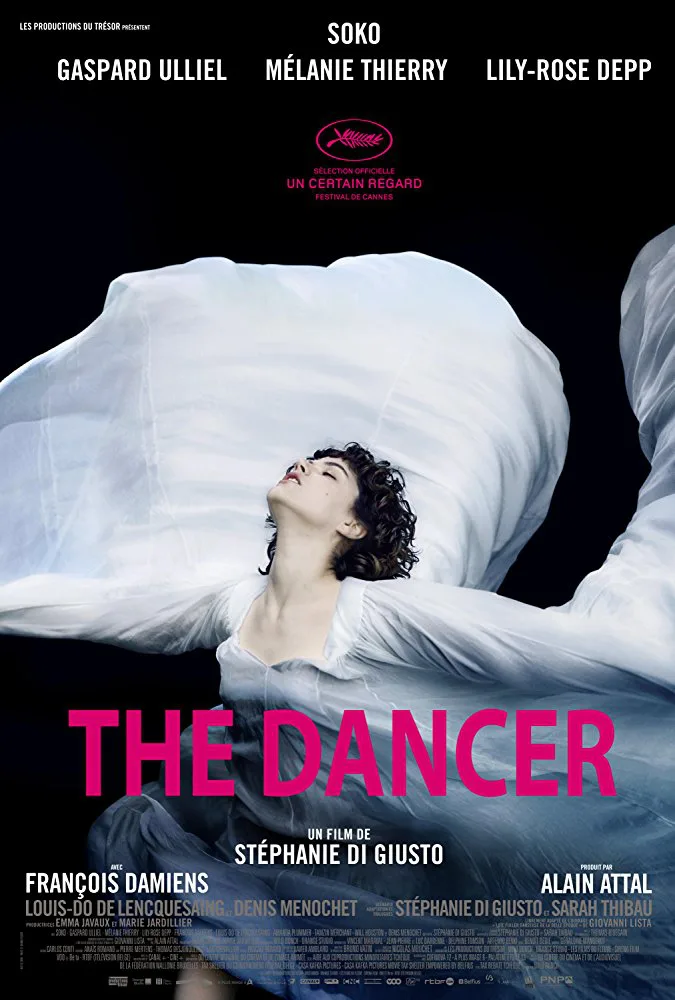

This unique artist, who packs plenty of opportunities for visual pizzazz, seems long overdue for big-screen treatment. And given that Fuller outwardly was more of a muscular tomboy than ethereal waif, first-time director Stephanie Di Giusto at least has gone outside the box when casting her lead. Her choice? A French singer-songwriter turned actress known as Soko, whose bobbed brunette hair and distinctly off-beat features suggest a not-unappealing blend of Erin Moran of “Happy Days” fame and Bjork.

But despite an on-screen claim that her movie is based on a true story, Di Giusto’s script plays fast and loose with many of the facts of Fuller’s history—none more so than the Old West prologue with her gold-prospecting father that involves both cattle rustling and recited excerpts of Oscar Wilde’s play “Salome.” When Dad is shot dead in an outdoor bathtub, Fuller high-tails it to Brooklyn and takes up residence with her Temperance-warrior mother (a wasted Amanda Plummer). That is when she decides to try stage acting. When her too-large costume begins to droop mid-scene, Fuller simply lifts her skirt and spins around. The audience approves, and suddenly a dance sensation is created and Loie is born.

Soon she will seek her fortune in Paris and become a sensation at the Folies-Bergere. But not before she meets her prime benefactor and semi-consort, the vampire-like composite character of Count Louis Dorsay (Gaspard Ulliel), who likes his rooms dark as tombs, his sexual partners for hire and his mood-altering ether readily available. Most of Ulliel and Soko’s scenes together tend to devolve into silent staring contests, including those at his mansion in the City of Lights. The property serves as both Fuller’s new home and her rehearsal space where she trains a chorus line of tunic-garbed young followers.

This is where the youthful Duncan comes in as Fuller’s seductive new student, slinky and sylph-like, whose style is more formal than intuitive. Before you can say “All About Eve,” Duncan—embodied by a teenage Lily-Rose Depp (the minx-like spawn of Johnny Depp and his ex, Vanessa Paradis)—is bewitching her mentor and soon-to-be rival out of her clothes in a garden at dusk before leaving her high and dry in more ways than one.

“The Dancer” clearly needed a better task master behind the camera. There are too many scenes of Fuller physically and mentally suffering for her art as she questions if what she does actually qualifies as dance. How many times do we need to see her soak her body in a vat of ice? Depp’s lone dancing interlude is achieved primarily by an obvious body double although her seduction of Soko is effective if brief. And, overall, the editing feels weighed down rather than spritely, as one would hope for a film about freedom of movement. Too many episodes either go on too long or are too short—as is the case with Fuller’s climatic and triumphant debut at the Opera House.

If there is joy to be found in this story, it comes from Soko’s sincere commitment, the staging of her re-creations of Fuller’s astonishing routines and the subtle facial nuances of Melanie Thierry as Gabrielle, her ever-alert loyal assistant and protector. But if a biopic about a dancer causes you to search the Internet to better learn more details about its subject while yearning for more musical numbers, that can’t be a good sign.

What is most damning is that Fuller was anything but a brooding loner, as she too often comes off as in the movie. Before dying from pneumonia in 1928, she would influence such artists and writers as Rodin, Toulouse-Lautrec and Yeats. She inspired both Ruth St. Denis and Martha Graham. You can even sense her impact on contemporary routines featured on the TV competition show, “So You Think You Can Dance.” She was given patents for her staging and lighting innovations, developed cinematic techniques and grew close to Marie Curie and her family. If only Di Giusto more ambitiously broadened her scope, she would have made a fleet-footed tribute for the ages instead of stumbling over such rich possibilities.