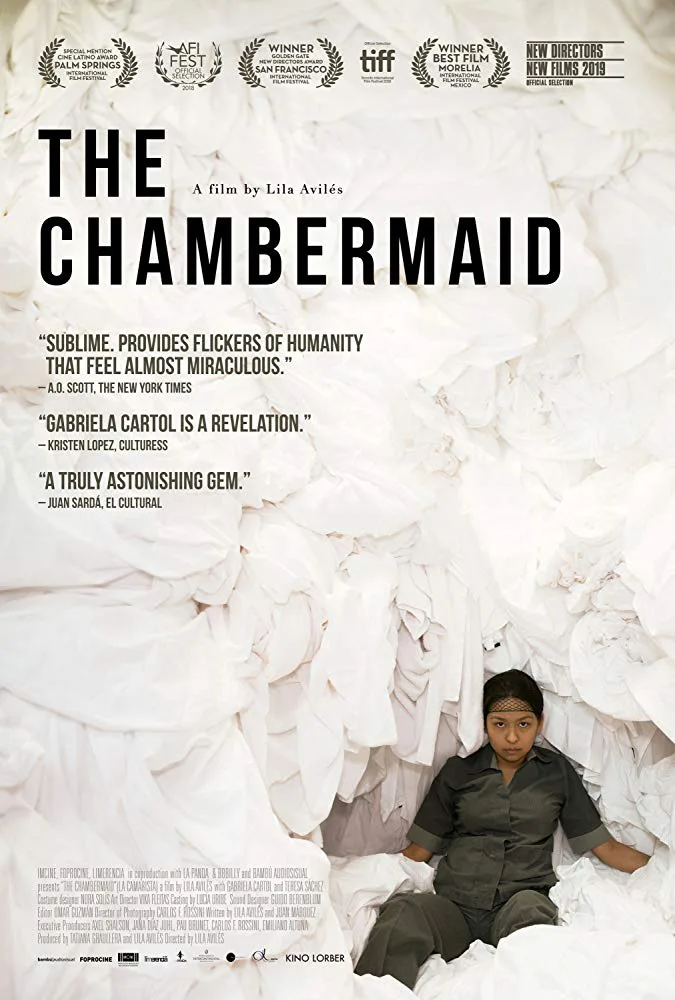

Slow, steady, and with an exacting eye for detail, Lila Avilés’ “The Chambermaid” is a painfully astute observational drama about a young woman working in one of Mexico City’s posh hotels. The movie closely follows Evelia or Eve (Gabriela Cartol), for short, on her daily rounds of dreary tasks. It begins at a low point of her day: picking up a particularly messy room with clothes strewn on every surface and everything out of place. She settles into a rhythm of working quickly and efficiently—bagging garbage, wiping surfaces and straightening up the place until she discovers a body at the bottom of a pile of sheets that had fallen on the floor. Fortunately, the guest stirs and acts more embarrassed and groggy than angry at being discovered by a member of the housekeeping staff. Eve excuses herself from the awkward moment. There’s so much left for her to do.

Later, the audience learns more about Eve. She works hard to provide for her four-year-old boy back home and enrolls in the hotel’s equivalent of GED classes so she can move up. At the cafeteria, she only takes a cheap snack as a way to bring home more money before spending it. There are subtle ways in which her job grinds on her self-worth, like when a supervisor scolds her and reminds Eve that she’s not to be seen by guests or to spend too much time in guest areas, like an innocuous elevator bank. Some of her co-workers have their own agendas, and they try to prey on Eve’s kindness for extra help or money. For the most part, guests treat her as if she’s invisible, except for one privileged Argentine new mom who relies on her to watch her baby so she can shower. Even when it seems that someone can see Eve as a person, something happens to remind the audience just how isolated our main character remains.

Avilés’ feature debut offers a snapshot of the under-appreciated and undervalued worker: the camera watches Eve closely with close-ups or medium shots, giving the audience a sense of Eve’s growing frustration with her environment. We can see her eyes fall every time she’s told to wait for a red dress she found that a guest left behind. We also see her steal away precious moments of privacy just to eat, call her son, relax or flirt. “The Chambermaid” doesn’t gloss over the laborious nature of her job—folding every bedsheet, dusting every surface, and so on—but it also captures how Eve invents ways to break the tedious routines. She’s curious about her guests, the books they bring and the things they throw out, making each room a different space for her to explore. Her duty-bound job may obscure her humanity to those around her, but the movie doesn’t lose sight of the qualities that make us more than cogs in a machine.

Cartol gives an incredibly nuanced performance as Eve. It’s thrilling yet painful to watch her pent up so much quiet frustration in her eyes. Like waiting for an unsteady stack of Jenga tiles, you don’t know when her emotions are going to come crashing down, but they most assuredly will—they must. Yet, even in the movie’s quieter moments, Cartol’s performance is just as effective. Her character is shy, and we see her struggle to navigate the social awkwardness of her co-workers trying to sell her their items or the rush of panic when she’s uncomfortable with a man’s attention. Cartol never has to spell out what’s Eve thinking about; her eyes tell us so much.

Just as Cartol’s subtle performance shapes the movie, so does the sleek, modern hotel where she works. Eve cleans these expensive rooms that cost way more than her meager paycheck. The clash between the classes is just as apparent as the hotel’s black and white interiors. In the world of the hotel staff, the setting takes on an industrial grey and peckish off-white colors. It’s a place that does not need to look good for guests, and is visually separated from anything that resembles the freedom or bright light the guests enjoy. Eve enjoys a few private moments in cramped supply closets and rooms under construction, creating a small space for herself in this bleak behind-the-scenes world.

Last year, “Roma” began many conversations about the depictions of housekeepers and domestic workers. “The Chambermaid” is somewhat a continuation of that conversation but without the burden of being based on someone’s memory. Avilés is more interested in the minutiae of her character’s life than making larger social commentary, her lens instead focused on Eve’s dull tasks, the family she calls often, and her ambition to move up in the hotel’s hierarchy. With her film, Avilés unlocks a world full of hope and disappointment, a workday that may bring peril or boredom. It may feel less epic in scale, but “The Chambermaid” is just as emotionally potent and perhaps even more successful at questioning the power dynamics of a workplace that has lost its sense of compassion.