“The Brotherhood of the Wolf” plays like an explosion at the genre factory. When the smoke clears, a rough beast lurches forth, its parts cobbled together from a dozen movies. The film involves quasi-werewolves, French aristocrats, secret societies, Iroquois Indians, martial arts, occult ceremonies, sacred mushrooms, swashbuckling, incestuous longings, political subversion, animal spirits, slasher scenes and bordellos, and although it does not end with the words “based on a true story,” it is.

The story involves the Beast of Gevaudan, which in 1764, terrorized a remote district of France, killing more than 60 women and children and tearing out their hearts and vitals. I borrow these facts from Patrick Meyers of the UnexplainedSite.com, who reveals that the Beast was finally found to be a wolf. Believe me, this information does not even come close to giving away the ending of the movie.

Directed by Christophe Gans, “The Brotherhood of the Wolf” is couched in historical terms. It begins in 1794, at the time of the French Revolution, when its narrator (Jacques Paren), about to be carried away to the guillotine, puts the finishing touches on a journal revealing at last the true story of the Beast. Although a wolf was killed and presented to the court of the king, that was only a cover-up, he says, as we flash back to …

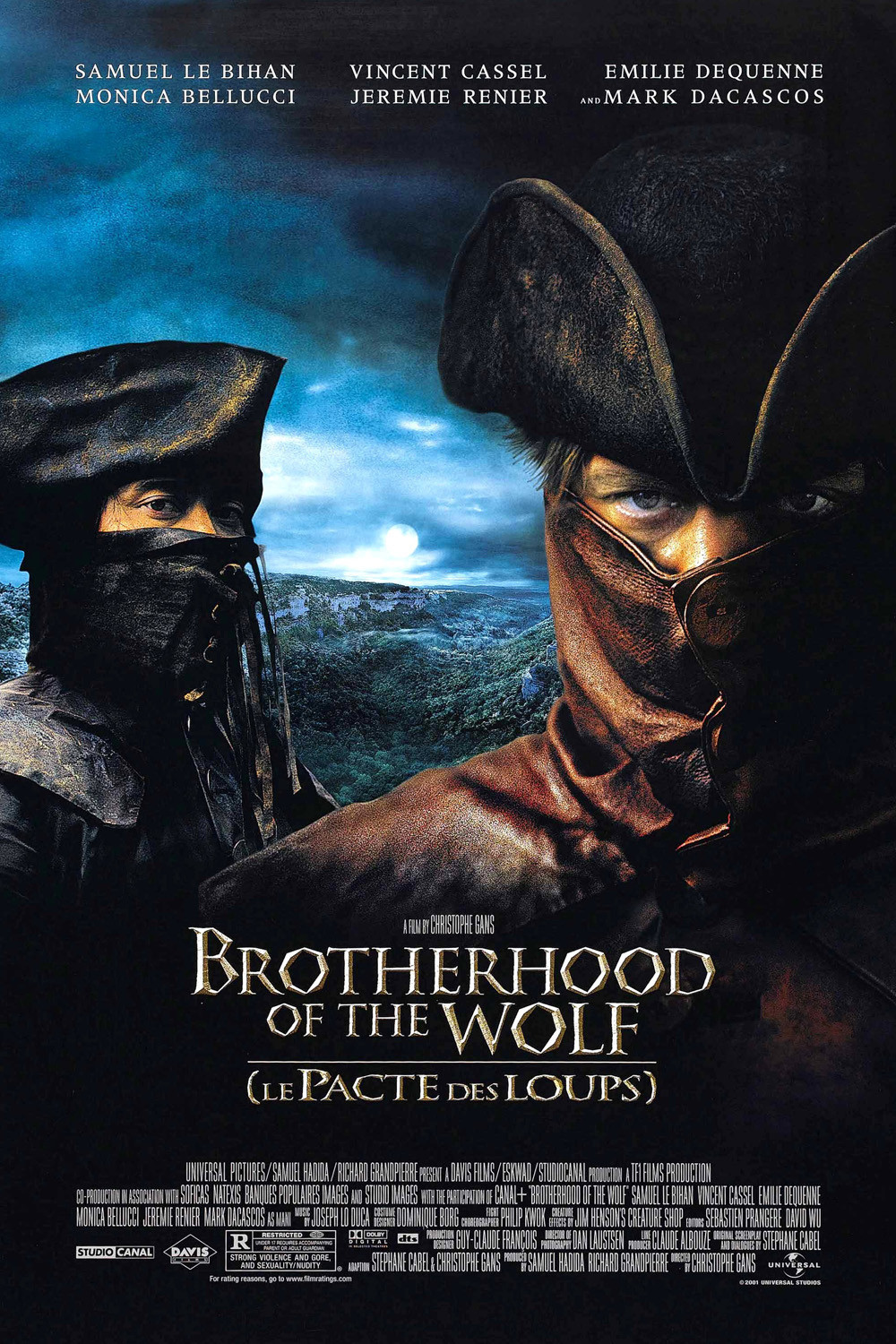

Well, actually, the Beast attacks under the opening credits, even before the narrator appears. For the first hour or so we do not see it, but we hear fearsome growls, moans and roars, and see an unkempt but buxom peasant girl dragged to her doom. Enter Gregoire de Fronsac (Samuel Le Bihan), an intellectual and naturalist, recently returned from exploring the St. Lawrence Seaway. He is accompanied by Mani, an Iroquois who speaks perfect French and perfect tree (he talks to them). Mani is played by Mark Dacascos, a martial arts expert from Hawaii whose skills might seem out place in 18th century France, but no: Everyone in this movie fights in a style that would make Jackie Chan proud.

Fronsac doubts the existence of a Beast. Science tells us to distrust fables, he explains. At dinner, he passes around a trout with fur, from Canada, which causes one of the guests to observe it must really be cold for the fish there, before he reveals it is a hoax. The Beast, alas, soon makes him a believer, but he sees a pattern: “The Beast is a weapon used by a man.” But what man? Why? How? Charting the Beast’s attacks on a map, he cleverly notices that all of the lines connecting them intersect at one point in rural Gevaudan. Fronsac and Mani go looking.

The local gentry include Jean-Francois (Vincent Cassel), who has one arm, but has fashioned a rifle he can brace in the crook of his shoulder. It fires silver bullets (this is also a historical fact). His sister Marianne (Emilie Dequenne) fancies Fronsac, which causes Jean-Francois to hate him, significantly. Also lurking about, usually with leaves in her hair, is the sultry Sylvia (Monica Bellucci), who travels with men who might as well have “Lout” displayed on a sign around their necks, and likes to dance on table tops while they throw knives that barely miss her.

I would be lying if I did not admit that this is all, in its absurd and overheated way, entertaining. Once you realize that this is basically a high-gloss werewolf movie (but without a werewolf), crossed with a historical romance, a swashbuckler and a martial arts extravaganza, you can relax. There is of course a deeper political message (this movie is nothing if not inclusive), and vague foreshadowings of fascism and survivalist cults, but the movie uses its politics only as a plot convenience.

“The Brotherhood of the Wolf” looks just great. The photography by Dan Laustsen is gloriously atmospheric and creepy; he likes fogs, blasted heaths, boggy marshes, moss, vines, creepers, and the excesses of 18th century interior decorating. He has fun with a completely superfluous scene set in a bordello just because it was time for a little skin. The Beast, when it finally appears, is a most satisfactory Beast indeed, created by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. There are times when its movements resemble the stop-motion animation of a Ray Harryhausen picture, but I like the oddness of that kind of motion; it makes the Beast weirder than if it glided along smoothly.

The one thing you don’t want to do is take this movie seriously. Because it’s so good-looking, there may be a temptation to think it wants to be high-toned, but no: Its heart is in the horror-monster-sex-fantasy-special effects tradition. “The Beast has a master,” Fronsac says. “I want him.” That’s the spirit.