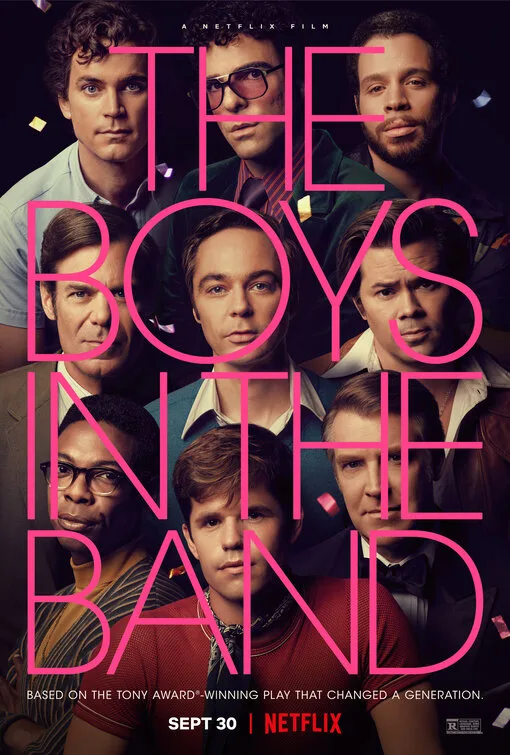

Back in 2018, Mart Crowley’s groundbreaking play “The Boys in the Band” was produced on Broadway to commemorate its 50th anniversary. This followed its original Off-Broadway run and its subsequent 1970 cinematic adaptation by director William Friedkin. As with that film, Netflix’s 2020 version lifts the entire stage cast to reprise their roles, resulting in a production that consists entirely of openly gay actors. The most familiar faces in the crew are Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, and Matt Bomer, whose presence ties this feature to his boss on numerous other projects, Ryan Murphy. Thankfully, Murphy only serves as a producer here, turning the reins over to the 2018 revival’s director, Joe Mantello.

Once again, Crowley adapts his material to the screen, this time collaborating with Ned Martel. The film is dedicated to the author, who died this past March, and wisely stays in the timeframe in which it was written. It’s the year before Stonewall, and six friends are throwing a party for their pal, Harold (Quinto). This shindig will unfold at the home of Michael (Parsons), their resident social butterfly and master of ceremonies. Michael has quit drinking, a decision noticed by the party’s first guest, Donald (Bomer). It’s implied that Michael is not a nice drunk, though his shenanigans while under the influence make for memorable post-party conversations and maximum shade throwing.

We also learn that Michael dreads getting older, fearing that his hairline is doing the moonwalk atop his head. Donald, who admittedly does not look like he’d be kicked out of bed by anyone with one iota of common sense, humors his former lover. As they chat, Michael prepares some hors d’oeuvres to go with the impending tidal wave of booze and the requisite birthday cake. The appetizer du jour is made from crabs, which one should always avoid at parties. Most of the guests heed this advice, creating a bit of a running joke as the night wears on.

Soon, we are joined by everyone but Harold, whose fashionably late appearances are notoriously expected and tolerated. There’s Emory (Tony nominee Robin de Jesús), the most flamboyant member of the crew, Larry (Andrew Rannells) and his soon-to-be-divorced partner, Hank (Tuc Watkins), and Bernard (Michael Benjamin Washington) who, to paraphrase Celeste Holm in “All About Eve,” is what the French would call “de Token.” You can bet your last money that, with Bernard in this bunch, somebody’s going to drop the N-word, and it isn’t going to be Bernard.

In addition to our starting lineup, there are two unexpected guests. One is Emory’s birthday present, a midnight cowboy (Charlie Carver) whose brain has comically stopped at noon. The other, far more ominous visitor is Alan (Brian Hutchison), Michael’s super-straight roommate from university. Alan’s in town and calls Michael to set up a meeting. When Michael explains he has a prior engagement with friends Alan won’t like, Alan suddenly begins to weep, shattering the tough façade Michael always knew him to have. Worried, Michael invites Alan over for a quick drink, warning his partygoers to, dare I say it, act straight until he leaves. When Alan calls later to reschedule, Michael is relieved. At least until the guy shows up anyway. When Alan realizes that, not only is he surrounded by gay men, but that his girl-crazy best mate at uni is also a member of that order, all Hell breaks loose.

One of Crowley’s more interesting dramatic details is how he makes Alan’s dilemma, that is, the reason he weeps and wants to see Michael, the play’s MacGuffin. The reason why Alan shows up unexpectedly, why he won’t leave even when his homophobic senses compel him to, and what he so desperately has to tell Michael are all left up to the audience’s devices. As the only “straight” character in the play, Crowley purposely makes him a bland, rather pathetic catalyst. Sure, he triggers Michael and pushes him toward the bottle, but other than that, he’s a deer trapped in rainbow-colored headlights.

There’s always a deliciously nasty bit of schadenfreude involved in watching a member of the majority squirm when forced into the minority-filled presence his privilege would normally allow him to avoid. When Emory challenges Alan’s rigid homophobia, Alan responds with the violence you’d expect from a man who’s very likely living a straight lie. But this is the only clue Crowley gives us about Alan’s true intentions. However, he also uses Alan to provide the play’s funniest moment, a vicious (and accurate) jab at heterosexual naïveté: When the straight-appearing Hank reveals he likes men, Alan exclaims “but he’s married!” The other men spontaneously explode with uproarious laughter rife with derision.

Here’s where Harold, late as usual, shows up in this review. He arrives just as Alan is attacking Emory and Michael is reintroducing himself to hard liquor. Like Michael, he’s concerned with his looks, but he preens and paws over himself in the mirror until he’s found (or applied) the courage to venture out. This supposedly explains his tardiness. As drunkenness turns Michael into the face that launched a thousand quips, Harold haunts the background of the party enjoying every bit of the mischief. He’s a wallflower with thorns and Quinto plays him superbly. Looking like a young Eric Bogosian cosplaying as a seedy Count Chocula, Quinto sucks up the drama like a vampire, so much so that, when his big moment arrives, we truly believe in the threat he aims in Michael’s direction. It’s the film’s best performance.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, unfortunately, is Jim Parsons. Michael is a tough role to play, and full disclosure, I saw this production on Broadway and had the same problem with the performance. This character is rigged to plumb some of the same depths Albee’s Martha does, but except for his final speech, where his reactions are genuinely powerful, Parsons is far too mannered and one-note here. By the time the film turns into “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bang Theory,” it feels like we’re watching a loop of the same scene.

This is most evident in the play’s centerpiece, a game where Michael challenges his fellow men to call the person they loved the most and tell them. The concept is a stroke of dramatic genius by Crowley, a bit of cruelty that is both sadistic and masochistic. It works like gangbusters in Friedkin’s original because Kenneth Nelson’s Michael anchors the sequence, finding the convincing, forceful bogarting I didn’t see in Parsons’ performance. Here, it’s less successful despite the excellent work by de Jesus, who breaks your heart, and Watkins and Rannells, who find bitter romantic comedy in their phone calls. Mantello keeps cutting away to flashbacks just as the actors are reaching high points in their monologues. He also ends the film with a very cheesy, literal representation that was entirely unnecessary. These diversions lessen the effect of the speeches, even if one of them provides an homage to Esther Williams’ underwater sequences that would have made an outraged Louis B. Mayer roar louder than his company’s logo.

That randy moment of skinny dipping occurs during Bernard’s phone call moment and, I’m sorry, I just could not deal with this character. Washington gives a good performance, but what he’s given to play is head-scratching at best. His arc feels like a segment of “Slave Play” presented by the Children’s Television Workshop. I know it’s 1968, but this part of the movie feels misguided and underwritten. There’s a potentially interesting set of events and race-based details worth investigating, but for such a daring work as this was, and is, it’s a rare moment where it feels like the play doesn’t understand a character.

“The Boys in the Band” has been accused of presenting gay men as self-hating, but at least for me, the emotions and traumas presented are far more complicated than that. Even though it’s a period piece, it’s still designed to evoke the same feelings in the current gay or bisexual viewer and to start the same important conversations about who we are and what we feel. I’ll keep saying this: representation matters, even if it’s as imperfect as Bernard.

For example, credit where it’s due for the moment Michael reacts after Alan catches him and his cronies dancing with one another. Even though it’s his house (and by extension, his rules), Michael still tries to keep up straight appearances for Alan’s sake. When Alan catches the dance number, and Michael turns around to see him, Parsons nails that horrified reaction, then tempers it with a subtle, growing sense of relief and defiance as the scene goes on. It reminded me of the moment when I was not yet out at work, and my boss walked by the gay bar I was drinking in; he looked in the window at the same time I looked out. He saw me and I froze for a moment, then I smiled and waved at him. You may experience memories like this when you watch “The Boys in The Band.” I prefer, and recommend, the original, but I’m on the fence about this one. Your mileage may vary.

Now available on Netflix.