John Lennon: “I’d like a fifth Beatle.”

Paul McCartney: “It’s bad enough with four.”

This exchange occurred in January, 1969, on Day 15 of the 22-day marathon rehearsal process for a television special/album/concert/documentary (the nature of the project changed by the day, sometimes by the hour). During those weeks they would lose George Harrison for a couple of days, and gain keyboardist Billy Preston. Sometimes John was a total no-show. On one day, only Ringo showed up. McCartney murmurs ominously at one point, “And then there were two.” “And then there were one.” And then there were none.

“Let It Be,” the film patched together from the mounds of footage by director Michael Lindsay Hogg, was released in 1970, right after the Beatles broke up. Because of that unfortunate bit of timing, the film was viewed not as a fascinating glimpse of four superstars in a working process, but almost entirely as foreshadowing, a retrospective portrait of the break-up as well as a commentary on “why” they went their separate ways. Yoko Ono, present in every scene by Lennon’s side, was reviled, and there are still people who think she is the reason the Beatles broke up. The overall result of the film is fairly grim, particularly for Beatles fans. They all look so glum and serious, there’s no sense of playfulness or even shared creativity. They sit holed up in separate corners, bickering, and there’s a sense that things are falling apart, and none of them care to stop the disintegration. It all culminates in the famous rooftop concert, with John, Paul, George and Ringo performing in the open air, like glorious wind-blown gargoyles hovering over the London streets. The album of the same name—the Beatles’ twelfth and final studio album—was released around the same time, and that, too, has a distinct thrown-together quality (but still! It’s the Beatles! They always leave you with something!). The footage of the Let It Be sessions (what we have seen, at least, thus far) has stood as the final word for 50 years, evidence that the band that changed the world went out with a whimper, not a bang.

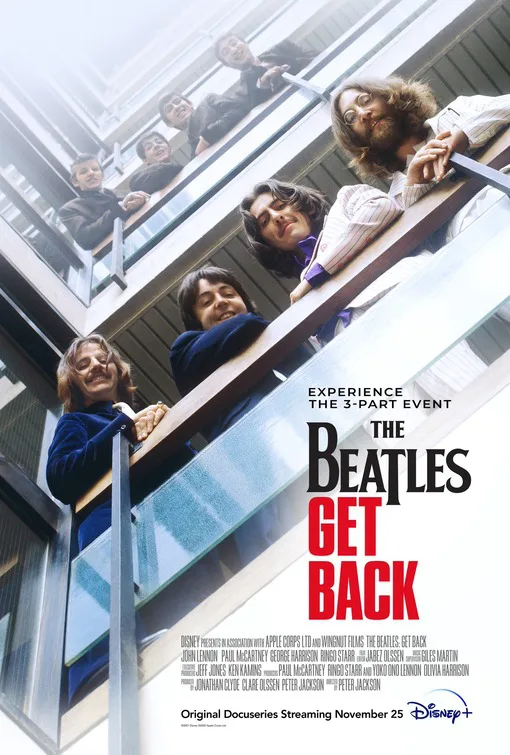

Life, of course, is complicated, and cannot be summed up in 80 fragmented minutes. Peter Jackson‘s dream was to get his hands on all 60 hours of the original footage, plus the 150 hours of audio, to see what else might be there, what didn’t make it into the depressing final cut. Jackson is not alone. The Beatles fandom has been waiting for this moment for decades. “Get Back,” released in three parts, encompasses almost seven hours, and gives an extraordinarily intimate and complicated picture of that month, when the Beatles gathered first at Twickenham Studios (this was when they still thought they would be doing a television special), and then at the recently-constructed Apple Studio (and its famous roof). Seeing all of this footage is a revelation, not just for how it provides a necessary counter to the prevailing narrative, but also because the visuals look like a total dream, pristine, sharp and clear, with no fuzz or distortion.

The first episode opens with a history of the Beatles from 1956 until 1969, presented at the speed of light. Jackson doesn’t linger on the preface. It’s a bulleted list—Hamburg to Liverpool to the Ed Sullivan Show to India and beyond!—a whirlwind, but necessary backstory. After deciding to stop performing live in 1966, the fab four retreated to the studio. Their experiments in over-dubbing and multitrack recording resulted in some of the most famous and influential albums of all time, but also meant they didn’t need to be in the same room at the same time anymore. This new project, though, was going to be different: For two weeks, they would “come together” and write a batch of new songs, which they would then perform live for an audience. The entire process, start to finish, would be filmed, for theatrical or television release. Director Lindsay-Hogg had directed episodes of England’s popular television show “Ready, Steady, Go!”, as well as the concert film “The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus”—in which John Lennon had appeared.

At first glance, things don’t get off to a good start. There’s a lot of messing around, a lot of playing the music that got them going in the ’50s—Eddie Cochran, Chuck Berry, etc. There’s no sense of urgency. Two weeks in, they still don’t know what it is they’re trying to even create. An album? A live television special? In two weeks? With what material? They keep coming back to the question of the live show and where it should take place. McCartney thinks it would be great to do it in the House of Parliament and get dragged away by the cops. Lindsay-Hogg repeatedly mentions an amphitheater in Libya. There are serious discussions for days on end of hiring a boat to bring an audience to Libya with them. It’s madness. Meanwhile, though, the real question looms: they’re supposed to be writing music to perform at this hypothetical live show. But … there’s no writing going on.

Until there is.

“Get Back” provides precious footage of famous songs coming into being, from start to finish, transforming from an idea, a hook, a chord, to a finished product. Paul creates Get Back out of thin air, and “out of thin air” is the artistic process: first there is nothing, and then there is something. It’s mysterious how it happens (even to artists) and it is such a gift to watch a song take shape, through trial and error, and repeat attempts to get to the core of what the song wants to be. From Paul trying out those opening chords in Twickenham to the four gargoyles howling the finished song up into the open air on the roof of Apple Studio is just a two-week period. There are other songs that came out of those sessions—”Let It Be,” for example—and we get to watch their creation as well. Ringo comes in with “Octopus’ Garden” and shows it to George, who helps him bring the idea into a fuller reality.

Even more of a revelation, though, is the overall vibe. Watching the original 1970 film, you can’t believe those glum guys didn’t break up sooner. Here, though, it’s not as clear-cut. There are so many moments of levity, of laughter, John and Paul goofing off, cracking each other up. (There’s a beautiful moment when they start jitter-bugging together.) Yes, there are moments of tension and disagreement, but that’s a normal part of any artistic process. When George quits, John and Paul have a private discussion, unaware of a microphone in the flower pot. The conversation is a breath-taking glimpse of their relationship. They decide to go and ask George to come back to the band. George does return, and Billy Preston arrives at almost the same time. Preston, an amazing pianist whom they befriended in Hamburg, joins the sessions, injecting a sense of purpose and focus into what had been rather aimless.

Yoko is there all the time, but so is Linda Eastman (later Linda McCartney), and Linda’s small daughter Heather (who is a much more disruptive presence than Yoko Ono!). Ringo’s wife shows up for some of the sessions. George Harrison brings a couple of Hare Krishna buddies, who sit in the corner rocking and praying. There was a lot more going on in those rooms than Yoko sitting next to John and tapping her foot. “Get Back” leaves so much space for the different rhythms of each day: sometimes things click, sometimes they don’t. John is always late. Paul gets irritated. Ringo is calm and beloved by all. George is over being treated like a hired hand.

It’s easy to forget just how young they all were at this point. Not one of them was thirty years old yet. John and Ringo were 29, Paul was 27, and George Harrison was just 25 years old. No wonder George flounced off after being bossed around. He was 25!

While there is so much here to discuss and debate and digest, what Peter Jackson has done is not so much “correct” the narrative as provide a wider perspective, allowing those four weeks in January 1969 to breathe, and giving those men—two of whom can no longer speak for themselves—space to show themselves to us with all their nuance, complexity, humanity.

Whole series screened for review. Now on Disney+.