I don’t want to appear close-minded, or to alienate our younger readers, but I have to admit that I’ve seen a sufficient amount of dementia in my own extended family that movies about it, particularly fictional ones, aren’t exactly the first things I look to watch these days. Of course, most movies with this theme of aged suffering tend to concentrate on its effects on the people around the sufferer.

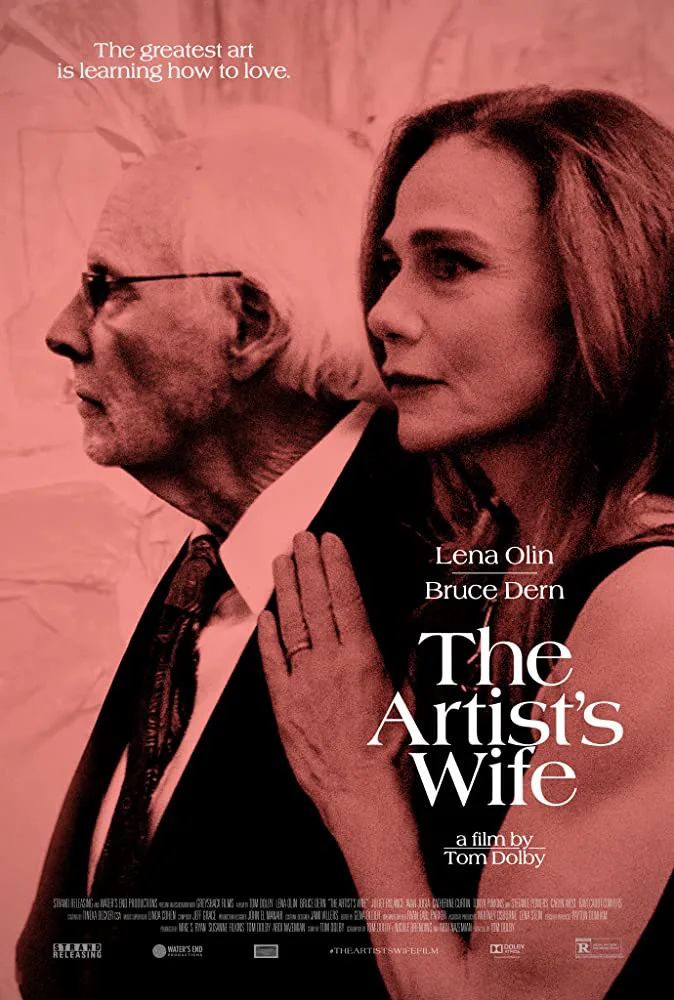

In the case of “The Artist’s Wife,” it’s Richard Smythson, a renowned painter played by Bruce Dern, who’s losing his memory and facility, and Lena Olin in the title role. Dern’s character is a doozy. The actor has been playing cranky old men now for so long you might be inclined to believe he was born one. He’s first seen, in rude health, on a television interview, talking about his beloved spouse Claire: “I create the art. She creates the rest of my life.”

So great, not only do we have dementia, we also have the Male Genius Narrative. Director Tom Dolby, who co-wrote the script with Nicole Brending and Abdi Nazemian, frankly depicts him as the most obnoxious male genius possible. Abusive to his students—he’s of the “I’ve suffered for my art, and now I’m gonna make you suffer too” school of pedagogy, and that’s putting it mildly—and imperious even as his ability to look after himself (which, frankly, he seems not to have done too much of even in his hardier days) dissipates.

So when Claire, worried (“I don’t know what happens when people disappear”) approaches Richard’s super-estranged daughter from a prior marriage, Angela (Juliet Rylance), one immediately takes the latter’s side in her determination to have nothing to do with her dad. But Claire wears away at her resistance, and arranges a visit to the couple modernist house in the woods, with Angela, her son, and their male babysitter. And boy, does that not go well.

“Richard can be unconventional,” one of the artist’s colleagues observes in a scene, and that remark speaks volumes about how such characters get coddled. As Richard himself fades, Claire takes up painting again. His recession is a kind of liberation. She finds inspiration from unusual sources, including Stefanie Powers as a conceptual artist. If you’re old enough to remember “The Girl From U.N.C.L.E.”—no? then how about “Hart to Hart?”—you may be stunned not just by her Natasha Fatale accent but by her … hell, I’m not going to spoil it. Fellow nostalgists, trust me: here’s your reason to check the movie out.

The dramatis personae is sufficiently constricted that it’s no surprise who Claire chooses to sexually stray from Richard with. What’s genuinely jaw-dropping, though, is what Claire determines to make her final gift to Richard. Amazing actor that she is, Olin makes us swallow it. But we don’t have to keep it down.

Obviously, one might argue that it’s unspeakably cruel to let a person who has gone through life behaving horribly (while using his status as an ostensibly important cultural figure as an excuse) just rot when he becomes sick like this. But the dénouement of “The Artist’s Wife,” wasting compassion on a character who has earned only the minimum, winds up fully validating an ideology and morality that is complicit in women’s oppression.