To watch Marc-André Leclerc climb is to see a great artist in his element.

Of course, the jaw-dropping ascents accomplished by this prodigious mountaineer are the work of a skilled athlete and a master technician. At such dizzying heights, to be anything less would undoubtedly prove fatal. The new documentary “The Alpinist,” directed by Peter Mortimer and Nick Rosen, is most electrifying in how it documents Leclerc’s preternatural calm, even as he free-solos some of the most hazardous mixed-climbing routes imaginable. Up high, where the rest of us would lose our nerve, this young man often appears to be dancing.

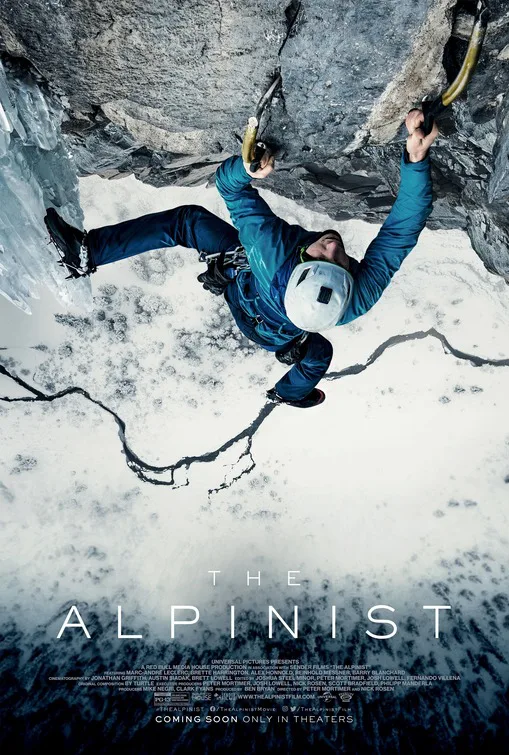

Consider this early scene: Scaling a steep limestone wall in the Canadian Rockies, a 23-year-old Leclerc reaches an overhanging ice section. Crampons scraping against rock, he swings one ice axe up and over, driving its pick into the frozen splash. Gripping one tool, Leclerc drops away from his perch, dangling in the air for a few terrifying moments before gently bringing a leg up to steady himself then swinging the other axe home. From there, it’s a small matter (relatively speaking, of course) of securing a better foothold and powering up the ice.

Far below, one documentarian lets out a relieved sigh (as did this audience member). But Leclerc keeps going. Soon, he’s soloing the area’s notorious Stanley Headwall, scraping his tools along the exposed rock of a 500-foot crag, at one point stowing his ax in a crevice to feel the limestone beneath his fingers. “The Alpinist” records this ascent with drone footage and more immediate handheld work; it’s an extended, exhilarating sequence and the film’s experiential peak.

However impossibly, Leclerc seems in scenes like these to belong to the mountains he climbs, traversing their granitic spires and glistening ice columns with intuitive grace. Each crevice, each invisible edge, reveals itself under his touch, and it’s breathtaking to observe his procession across such steep faces. Climbers often talk about a zen-like state of “flow,” in which one’s body and mind are in perfect alignment and at which point one’s skills are ideally matched to the challenge ahead. As “The Alpinist” suggests, Leclerc doesn’t just live in this flow state; it’s his higher power, and he withdraws to it as a disciple to the divinity, or perhaps a moth to the flame.

Mortimer and Rosen, who run adventure film company Sender Films, are both veteran climbers who’ve spent 20 years documenting the sport. They make no pretense of impartiality, whether stressing that they spent two years filming Leclerc or expressing their anxieties about the fact he could have fallen to his death at any moment.

And alpinism, in particular, kills around half of its ardent practitioners. Even amongst hardcore climbers, its dangers aren’t easy to defend. And yet, “if death were not a possibility, coming out would be nothing,” opines one talking head, alpinist Reinhold Messner. “It would be kindergarten, but not an adventure, not an art.”

It would be tough for any climbing documentary released soon after Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin’s Oscar-winning “Free Solo” (2018) to escape the long shadow of its larger-than-life subject, rock climber Alex Honnold. To their credit, Mortimer and Rosen don’t even try, having Honnold introduce LeClerc as if to personally endorse us turning our attention from that documentary to this one.

“Who impresses you right now, as a climber?” interviewer Tim Ferriss asks Honnold in the film’s opening minutes. The begrudging respect clear from his tone, he answers, “This kid Marc-André Leclerc.”

And the young age at which Leclerc accomplished his most death-defying feats is in large part what makes him such an intriguing blank slate. “The Alpinist” doubles back to fill in Leclerc’s early years, looking to pinpoint what turned him into a world-class climber. But aside from noting that Leclerc was diagnosed with ADHD and exhibited an addictive personality, which led him to experiment with drugs for a time, it draws no firm conclusions as to what drove him up this particular wall.

Honnold assesses Leclerc as having a more spiritual approach to climbing, compared to his own more athletic background. “The Alpinist” generally bears this out. As intensely physical as climbing is, the sport is even more psychological. It’s for this reason that climbers call routes “problems” before setting about solving them. To Leclerc, though, it appears a powerful stabilizing force. However paradoxically, he’s at his most grounded mid-ascent.

Early in his career, Leclerc scaled walls in total anonymity, and “The Alpinist” leaves you with the impression he’d have preferred it to stay that way. In interviews, he’s modest and camera-shy. The filmmakers lean hard on talking heads—from Leclerc’s mother to his girlfriend, fellow climber Brette Harrington, and a revolving door of renowned alpinists—to both detail the perils of his high-adrenaline pursuits and bring into focus the scale of Leclerc’s achievements.

Leclerc himself goes dark around the midway mark, frustrating Mortimer and Rosen. For a time, they wonder if they still have a film and despair that Leclerc’s latest triumphs—glimpsed on other climbers’ social-media feeds—are happening entirely off-camera. Eventually, they strike a deal: Leclerc will complete his new climbs solo then return at a later date with the filmmakers. “It wouldn’t be a solo to me if somebody was there,” he explains.

At times like these, you start to resent “The Alpinist,” which aims to capture what is, in essence, a private universe. Leclerc is a shrinking violet down here and a force of nature up there; this makes all the sense in the world once one realizes that climbing is, to him, the purest kind of transcendence. And whatever their intentions, Mortimer and Rosen’s camera evokes in Leclerc a sense of self that’s not only absent from but counter to his art form.

“Free Solo” wrestled with one major ethical dilemma around filming Honnold’s impossible free climbs: “What if he falls?” But Honnold was a willing subject, exuberantly charismatic despite a scary commitment to his craft. (This was part of the problem; the directors filming him feared their presence would distract Honnold or encourage to overreach.) Leclerc is a different kind of climber, and “The Alpinist” brushes up against different questions as a result. For one: who benefits most from continuing to film Leclerc, who expresses little interest in having his exploits documented?

To say too much about where “The Alpinist” ends up would disrespect certain structural choices made by the filmmakers, though any climbers in the audience likely know where Leclerc’s story is heading. Ultimately, Mortimer and Rosen’s film succeeds most as a sincere, wonderstruck tribute to a fellow climber. And if glorifying a sport as lethal as alpinism itself runs a kind of risk, there’s no denying the heart-in-mouth thrill of watching Leclerc in the zone, following an impossible dream and, on his own terms, touching the sublime.

Now playing in select theaters.