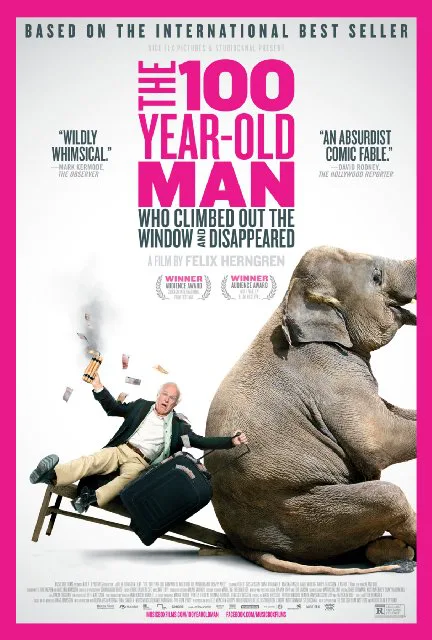

“What’s the highest grossing Swedish movie of all time?” you ask. Wait, no, you didn’t ask? Well, too bad. The highest grossing Swedish movie of all time, apparently, is this one, new to U.S. release, and watching it, one can see why. The Swedish film industry is one of the oldest and most advanced in the world—during the teens and ‘20s of the 20th century, its output was absolutely on a par with what the greatest innovators of the U.S. and France were up to—but it is often associated with a kind of dourness, on account (somewhat unfairly) of Ingmar Bergman and his death-occupied allegories. Even Sweden’s popular culture is pretty dark—it’s from this country that the dark thrillers of Steig Larsson hail. This movie, as it happens, is a comedy, but it’s a frequently grisly one, and one that makes rollicking fun of a lot of dark Swedish preoccupations.

Its plot is very neatly summed up by its title, which was also the title of the bestselling novel upon which it is based. The movie begins with a dynamite fuse crackling through the opening credits; then, its aged hero, Allan, puts his cat Molotov outside for a bit, and the poor kitty is killed by a coyote. Allan takes his revenge by blowing up the offending creature. This action lands him in a nursing home, out of whose window he climbs on his 100th birthday. The nursing home staff never finds him (that’s not really a spoiler), but we follow him on his subsequent adventure, which is intercut with his narration and flashbacks of his picaresque 100-year life.

“All I ever want to do is eat, sleep, and blow things up,” Allan avers at one point. A cruelty inflicted on him in childhood precludes (or at least inhibits) romance, leaving him with those three easy-to-fulfill desires. The blowing-things-up part is part of what gave this story particular appeal to Swedes. Sweden was, of course, the home of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite whose subsequent guilt about it led to the Nobel Peace Prize. Sweden’s national character, apparently, is at least partially defined by the paradox that this peace-loving, ostensibly “progressive” country is most notable in 20th-century world-historical terms for advancing the science of explosives. And so we see Allan cavorting through the century, blissfully free of ideology or perspective—a more well-spoken, self-aware Forrest Gump, if you please—encountering the likes of Franco and Oppenheimer and Stalin, and just happy to make things go boom the whole while. In the present day, he stumbles upon a suitcase full of cash, makes an accomplice of a rascally railway station agent, helps rescue a circus elephant, and more, all while thoroughly flummoxing a motorcycle gang who want the cash and the extremely understaffed and indolent police force that’s pursuing him. That last element is a bit of a subtle counter to the depiction of Swedish cops in the aforementioned Steig Larsson books.

Still you don’t have to be Swedish to enjoy the film. The picaresque mode is one that’s well-liked throughout Western culture, and this movie, directed by Felix Herngren and starring popular Swedish comedian Robert Gustaffson, executes it reasonably well, with touches not just reminiscent of “Gump” but of “The Shawshank Redemption” and other popular tall tales of our time. It is ever so slightly more cynical and in-your-face with mordant humor than a mainstream American film would have been; the insouciant treatment of Allan’s first experiment with dynamite is more Adam Rifkin than Robert Zemeckis. Such slight tonal eccentricities didn’t quite do the trick for this reviewer, however.