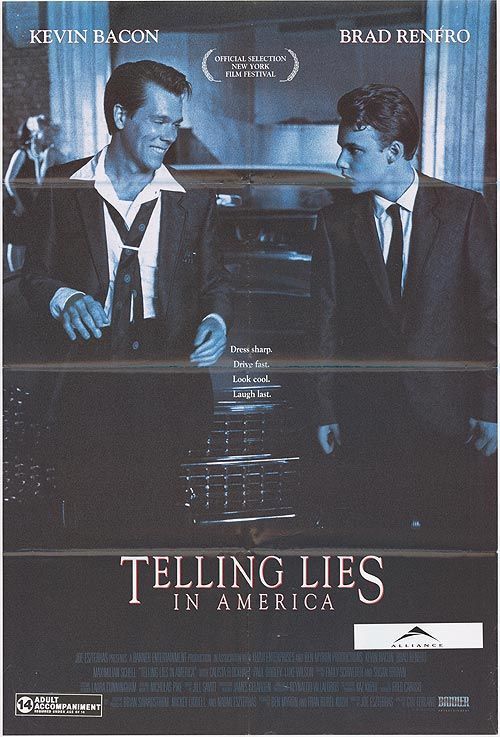

Cleveland, 1960. “I haven’t been Billy Magic since Fort Worth,” says the lanky, chain-smoking disc jockey. He has the grin of a man who is getting away with something. He is. “Telling Lies in America,” based on the memories of America’s top-paid screenwriter, Joe Eszterhas, is about the kid who helps Billy get away with it, and does a lot of growing up in the process. He gets a break and loses his innocence at the same time.

Karchy Jonas (Brad Renfro) is a student at a Catholic high school attended mostly by rich kids, who call him “white trash.” His father (Maximilian Schell) is a Hungarian immigrant, who was a professor in the old country but is a janitor in this one. Karchy works for an egg dealer in the local produce market, and has a crush on a girl who tells him she’ll date him, but only if he’s picked for Billy Magic’s “High School Hall of Fame.” Hall of Famers are supposed to be nominated by their classmates, but Karchy forges the signatures, sends them in, and wins. What he doesn’t know is that Billy Magic is looking for a cheater. “You lie good, kid,” he tells him, but even after he gives Karchy a $100-a-week job, the kid won’t admit he was lying. That’s good. It’s the time of the payola scandals, and Billy needs an underage bag man who can’t be forced to testify.

Eszterhas, who has made a fortune with screenplays like “Basic Instinct” and “Showgirls,” has had this story in the works for 15 years. Himself a Hungarian immigrant who came to Cleveland as a child, he remembers what success looked like from the outside. To Karchy, Billy Magic is a star. And the kid soon centers his life on the radio station, letting his grades slip because school is no longer where he expects to find his future.

Kevin Bacon’s work as the disk jockey is one of his best performances. He never pushes it too far: His style is laid-back cool, rather than frantic. His lazy announcer’s drawl suggests a cynicism developed during a career on too many stations under too many names. When the kid tells him he’s got it made, Billy explains about his ex-wives, his child support payments, and the fact that his red Cadillac convertible is leased. He’s one jump ahead of his next market.

Brad Renfro is assured and involving as Karchy. Amazingly, he’s playing over his age; Renfro (so good as the young boy in “The Client” in 1994) was 14 or 15 when he played this 17 years old; it is a nuanced performance, showing a character who has been so wounded by life (his mother is dead, his father embittered) that, yes, he’ll lie to get what he wants. And in an unexpected twist at the end of the film, lying pays off. (At one point, he advises the girl to read Huckleberry Finn–a nod to his previous role, as Huck in “Huck and Jim.”) The movie’s weak point is Karchy’s father, as played by Schell. Mr. Jonas is a weary assortment of cliches about immigrant dads: He always wears his hat in the house, has stringy hair and needs a shave. We are told this man was a professor and famous doctor in Hungary. It is more likely that he would dress according to Old World standards, however old his clothes. He wouldn’t seem so self-demeaning and clueless, forever moping around at home waiting for his son to walk in. A smarter character would have led to a better relationship.

But that’s a small point. I liked this movie a lot–not just for Bacon and Renfro, but also for the work of the wonderfully-named Calista Flockhart, as the girl who dates Karchy even after he unwisely tries to give her Spanish fly. What I’ll remember best about the film is Billy Magic, who does what he does, knows what he knows, and is intimately familiar with the underside of fame.