The term “eye-popping” could have been coined to describe Thai writer-director Wisit Sasanatieng’s “Tears of the Black Tiger,” not only for its retina-smacking colors, but because some eyes actually get popped. And some brains and lungs and other viscera, too. Bloody and syrupy, tragic and silly, this retro pastiche stands with its right foot in melodrama and its left in camp, shifting its weight woozily from one side to the other like a drunken Sergio Leone gunslinger straddling the camera.

The filmmaker says his movie is a send-up of, and homage to a lost, disreputable Thai action genre of the 1960s known as Baberd poa, Khaow pao kratom (“Bomb the mountain, burn the huts”) — with a little bit of Likay, a form of minimalist folk theater (performed against simple painted backdrops) thrown in. Western viewers will respond to the stylistic quotations from Leone’s spaghetti Westerns (including the drip on the brim of a 10-gallon hat from the opening of “Once Upon a Time in the West”), the slow-mo geysers of blood from Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch,” and the splatter and gore from George Romero’s zombie pictures, filtered through a sensibility that parodies not only these films but the postmodern comic book violence and cartoon characterizations of filmmakers like Sam Raimi, John Woo, Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez.

All of this plays out on ultra-stylized sound stages (and garishly tinted locations that look like sets) from what could be an Expressionist Thai stage production of “Oklahoma!” In an early shootout scene, in a field at sunset, Sasanatieng makes sure you can hear the echo of the theater itself as the actors project their lines to the balcony.

The story is like a tangled string of colored lights — purely decorative but pretty to look at. It begins in the middle, then moves backward and forward, with more flashbacks than a Dead reunion show. What it comes down to is this: Poor young Seua Dum (Suwinit Panjamawat) bonds with beautiful young Rumpoey (Stella Malucchi), but an unfortunate occurrence separates them. Ten years later, they are briefly reunited and declare their love for each other, but more unfortunate circumstances intervene to keep them apart.

Dum falls in with bandits and gains notoriety as the quick-shooting Black Tiger (now played by Chartchai Ngamsan), while Rumpoey’s father arranges for her engagement to police Capt. Kumjorn (Arawat Ruangvuth), who swears to kill or arrest all the bandits — one of whom, the second-fastest gun in the East and the Black Tiger’s rival, Mahasuan (Supakorn Kitsuwon, wearing a mustache that seems to have been made of slivers of electrical tape that go a bit askew when he’s drunk), takes an oath before Buddha to be loyal to the Black Tiger after the latter saves his life. Fights, betrayals, reunions and explosions ensue. (These cowboys carry more than pistols; they have machine guns and bazookas!) But how much of it is parody and how much of it is simply playing by the old reliable generic rules? There’s no way to tell, really, because Westerns and star-crossed love stories and convoluted serials (the primary ingredients in this corny stir-fry) have long relied on getting the audience to respond emotionally to patently artificial, even absurd, characters and situations. That’s one reason why we love genre pictures: They’ve always been self-aware to some extent, and it’s doubly satisfying when they follow the rules and acknowledge them (or kid them), too.

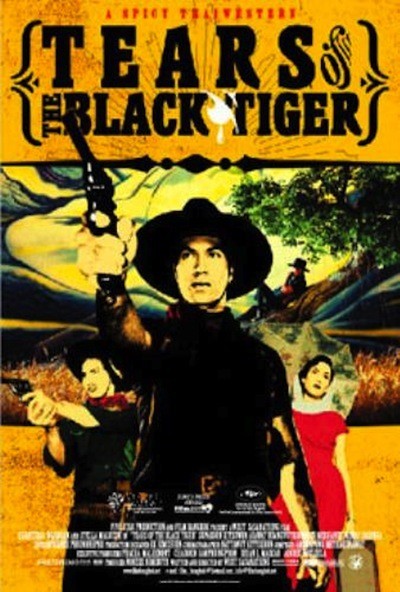

Thai cuisine is celebrated for its combination of flavors: salty, sweet, spicy and savory. And so it is with “Tears of the Black Tiger,” which mixes genres, tones and film styles to a similar effect. And colors — most of all, colors. The movie is a riot of tropical turquoise, magenta and pink, spiced with marigold, red and green. You’d swear it was drenched in a tangy tamarind sauce. (The colors were achieved, the director said, first with paint and lighting, then with tweaking on digital-Betacam video before transfer back to 35mm film.)

“Tales of the Black Tiger” was shown at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival where, after a successful screening, it was snatched up for U.S. distribution by Harvey Weinstein and promptly placed on Miramax’s infamous shelf until it was recently rescued by Magnolia Pictures. Today, in the era of YouTube, we might consider the movie a “mash-up” — a deliberate collision of diverse styles and sensibilities. And at 110 minutes, it begins to feel like maybe an 8-minute YouTube short would have worked even better than a full-length feature. After a while, I began to feel a little guilty, like I was sitting inside watching sitcom reruns on sunshiny day when I should have been doing something a little more constructive with my time.