Chinese director Jia Zhangke can be understood as a documentarian even when he’s making fiction films. His recent features on the rapid social and related ethical/moral changes in certain regions of mainland China have a keen grounding in reality, even when they branch off from the present day and speculate on the future, as his 2015 “Mountains May Depart” does.

Interestingly, though, while his fictional films have become more directly linear and concerned with narrative momentum than his early work, his actual documentary work maintains a complexly textured and sometimes elliptical feel. “Swimming Out Till The Sea Turns Blue,” Jia’s first documentary feature in about ten years (the last was 2010’s “I Wish I Knew”) lays itself out in 18 “chapters,” some running less than three minutes, each one on a theme or person, and the filmmaker has said these chapters were conceived to feel like clouds of different shapes and sizes.

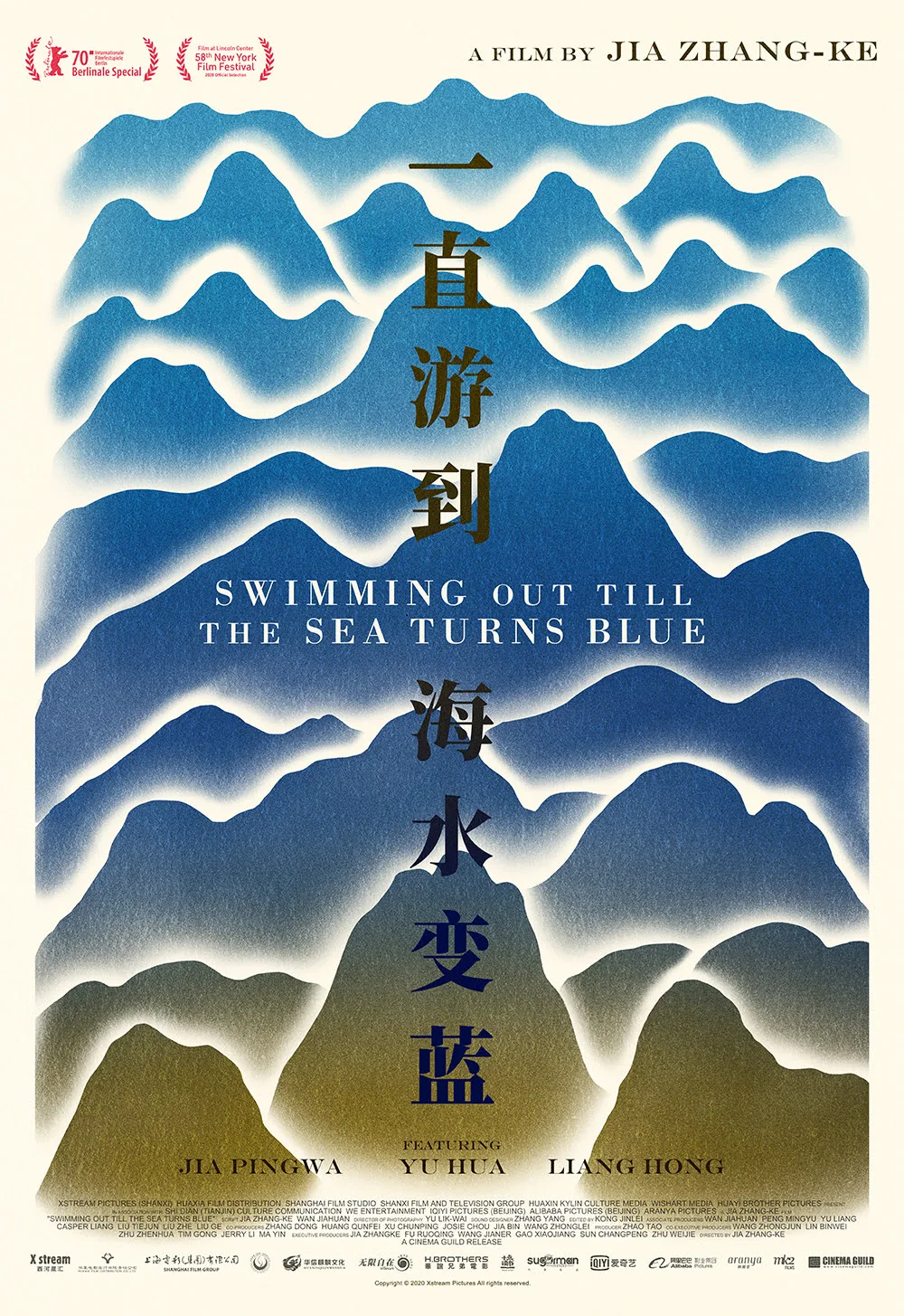

This is a conceit that maybe aspires to the metaphorical condition of music, but Jia here is taking a look at contemporary Chinese literature. Jia is from the province of Shanxi; in that province is a place called Jia Family Village (no relation, so to speak) that holds an annual festival of literature. Jia includes brief snippets from readings by a great number of writers, but focuses particularly on four, three living—and born in the ‘50s, ’60s and ‘70s respectively—and one dead. The living writers are Jia Pingwa, Yu Hua, and Liang Hong; of these three, Yu Hua is the one most comprehensively translated into English. These three have long segments in which they speak to the camera, that are interspersed with “clouds”/chapters on topics like “Eating,” “Disease,” “Returning Home,” and more.

Nobody really speaks of writing as such. Rather, the speakers recall difficulties in their home villages, challenges to agricultural development, the impact of the Cultural Revolution, and more. Jia occasionally blends some archival footage in the mix but the scenes are mostly of the contemporary life that surrounds these writers. Sounds from the natural world are drowned out by pings and chimes and clatter of electronic devices. One speaker muses that “remembering the past or longing for your native place are ways of reaching for reassurance.” They can also be ways of turning down the noise of today’s world.

The portraits here, which end with a chat with Liang Hong’s teenage son, a creature of postmodernity, are sensitive and intriguing. One feels obliged to emphasize though that Jia’s movie is one that’s primarily pitched at Chinese audiences, its larger universal resonances notwithstanding. If you’re not too conversant with the regions or works under consideration, the viewer has a choice of laboring to connect the dots unassisted, or just kicking back and letting the people and their recollections and philosophical reflections wash over you, like the sea of the movie’s title.

Now playing in theaters.