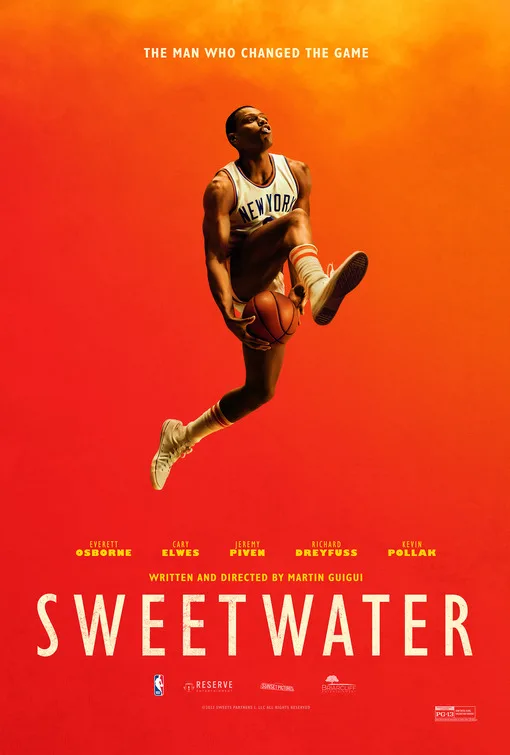

The forces who made this magical negro biopic about pioneer basketball player Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton (Everett Osborne) were well-intentioned, but the film is clearly wretched. “Sweetwater” begins with a hoops beat writer (Jim Caviezel) stepping into a yellow taxicab in Chicago in 1990. The audio of a Bulls game featuring highlights of Michael Jordan’s play echoes in the background. In the foreground, the driver asks if this grizzled reporter knows anything about the former greats: Julius Erving, Connie Hawkins, and Elgin Baylor. In a way that suggests an initiation, the reporter counters with David Thompson and Oscar Robertson. He’s earned the right to learn this mysterious driver’s name and story: He’s Sweetwater. What begins with a frame recalling “Driving Miss Daisy,” unfortunately, quickly descends into “The Legend of Bagger Vance.”

The film fades into New York City in 1949. The world champion Minneapolis Lakers face the Harlem Globetrotters in a barnstorming exhibition game, and Sweetwater is the clear star. The Globetrotters, a clown basketball team of Black players and athletes, are trying to ply their trade in the one arena available to them. They dream of becoming a professional basketball team once the segregated NBA realizes its best chance at survival and growth is to adopt the “razzle, dazzle play” of African-American “streetball.” We see intricate crossovers and passes behind the back, audacious hoops, and fun gamesmanship.

And yet, the filming of the actual gameplay leaves much to be desired. I can’t decide if it’s the flat, turgid lighting meant to elicit nostalgia for Converse shoes and long socks or the absentmindedness for anything resembling an evocative composition. You’ll find more electric pacing and sharper thrills in an NBA 2K video game than here.

This isn’t the only instance in which writer/director Martin Guigui (who’s been working since 1996 to get this film made) appears allergic to warmth and color. A pained flashback to Sweetwater’s childhood withers into a pallid, gray picture as young Nat picks so much cotton with his sharecropping parents that the stems pierce his hands. Every so often, as if to remember his roots, he can be caught staring at his famously broad hands as he searches for answers, solace, and help. The recurring motif suggests magicalness in Sweetwater, a divinity that carried him from unlikely circumstances to unthinkable superstardom.

But in this segregated landscape, there seem to be few mechanisms to bring Sweetwater from boondock throwaway games to NBA professionalism. Abe Saperstein, the Globetrotters owner, won’t let him out of his contract; he’s too big of a moneymaker. Ned Irish (Cary Elwes), the owner of the New York Knickerbockers, would rather not defy the league’s gentleman’s agreement not to draft Black players. Only Joe Lapchick (Jeremy Piven) sees Sweetwater’s potential and is willing to invite the ire of other white folks by taking the plunge. While these characters appear to have clear-cut motivations, they often veer from pro-integrationist policies to exoticized capitalism (a Black player, no matter how good, can sell tickets) and strong currents of racism. These turns rarely acknowledge the personal and political contours inherent to any human. Instead, they’re low-hanging patronizing fruit.

You can sense that condescension in the film’s unnatural development, as seen in commonplace scenes of prejudice: Eric Roberts briefly appears as a bigoted service station owner that shouts the Black Globetrotters away from his gas by touting a double barrel shotgun; a hotel rents a room to the monkey Mr. Bananas rather than the Globetrotters; an NBA owner during a league meeting bangs his fist on the table to exclaim, “It’s not a Negro league, and it never will be.” None of these people feel real. They’re the Montgomery Ward catalog of racists common to so many Civil Rights movies, they’ve become noxious cliches, particularly in this drab script, which feels like an AI chatbot wrote it.

The actors, admittedly left adrift in this reductive narrative, appear to sleepwalk on low-effort mode: Richard Dreyfuss plays league president Maurice Podoloff with little panache, and Piven doesn’t even bother to shave his beard to fit the appearance of not just the real-life-person he’s playing, but a coach of the period.

Throughout the film, you always wonder where “Sweetwater” wants to end or who it cares about. It all culminates in Sweetwater’s NBA debut, but even that game lacks integrity. The refs call glaringly racist fouls on Sweetwater and his radical game, only in the waning seconds to mysteriously flip and call the game his way. The announcers, who might or might not be cheekily calling the game, spiral into “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story” territory with every line of on-the-nose nauseating dialogue like, “His flashy play has thrown a curveball into the NBA.”

Not content with simply portraying a Black pioneer like Sweetwater as human, Guigui hoists him to mythical and magical status, racked by the torture of otherness. “My game don’t belong here,” says Sweetwater, in a belabored manner not unlike Michael Clarke Duncan’s “I’m tired, boss” in “The Green Mile.” His life isn’t his own; his success becomes the self-congratulatory success of every moderate, neoliberal white person who populates the film. Even the racist cop is given a beat of redemption when he compliments Sweetwater with “good game.”

We later return to that cab for no great reason other than how the film began. “I’m just the messenger,” says Sweetwater, spreading the gospel to white people about the Black superstars who came before MJ. The main problem, however, is that the film chosen to deliver that message is rotten.

Now playing in theaters.