John Sayles’ “Sunshine State” looks at first like the story of clashes between social and economic groups: between developers and small landowners, between black and white, between the powerful and their workers, between the chamber of commerce and local reality. It’s set on a Florida resort island, long stuck in its ways, that has been targeted by a big development company. But this is not quite the story the setup seems to predict.

If the movie had been made 20 or 30 years ago, the whites would have been racists, the blacks victims, and the little businessmen would have struggled courageously to hold out against the developers. But things do change in our country, sometimes slowly for the better, and “Sunshine State” is set at a point in time when all of the players are a little more reconciled, a little less predictable, than they would have been. You can only defend a position so long before the needs of your own life begin to assert themselves.

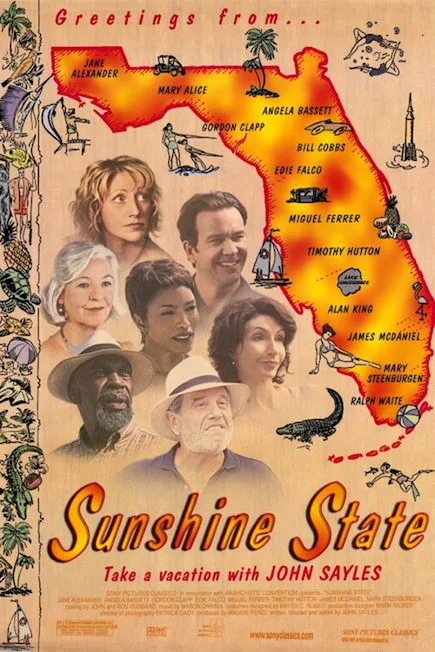

The island, named Plantation Island, consists of Delrona Beach, a small community of retirees and retail stores, and Lincoln Beach, an enclave of prosperous African Americans. Both groups have been targeted by a big land development company probably owned by a white-haired golfer named Murray Silver (Alan King), although he exists so far above the world of the little people that it’s hard to be sure. The company wants to buy up everything and turn it into a high-rise “beach resort community.” That would doom the Sea-Vue Motel and restaurant, which is run by Marly Temple (Edie Falco of “The Sopranos”). The motel was built by her parents, Furman and Delia (Ralph Waite and Jane Alexander), and is Furman’s life work. But it is not Marly’s dream. In a movie made 20 years ago, she would be fighting against the capitalist invaders, but, frankly, she wants to sell–and she even begins a little romance with Jack (Timothy Hutton), the architect sent in to size things up.

Over on the Lincoln Beach side, Eunice Stokes (Mary Alice) lives in her tidy white house with a sea view. When she bought this house, it represented a substantial dream for an ambitious black couple; today, it looks a little forlorn. For the first time in years, her daughter Desiree (Angela Bassett) has come to visit. Desiree got pregnant at 15 with Flash Phillips (Tom Wright), a football hero, and was sent away because Eunice was too proud of her middle-class respectability to risk scandal. Desiree has prospered on TV in Boston, and returns with an anesthetist husband.

Flash Phillips, meanwhile, has not prospered. He suffered an injury on his way to the Heisman Trophy, and now sells used cars. Success seems to go wrong on this island; while Francine, the bubbly chamber of commerce pageant chairwoman (Mary Steenburgen) narrates a story of pirates and treasure, her husband tries to kill himself, although neither hanging nor a nail gun do the trick. He’s got business difficulties.

Because we are so familiar with the conventional approach to a story like this, it takes time to catch on that Sayles is not repeating the old progressive line about the little guy against big capital. He has made a more observant, elegiac, sad movie, about how the dreams of the parents are not the dreams of the children.

Because Furman wanted a motel, Marly has to work long hours to run it. Because Eunice wanted respectability, Desiree had to run away from home. Because the chamber of commerce wants a pageant about “local history,” Francine has to concoct one. (The island’s real history mostly involves “mass murder, rape and slavery,” she observes, so they’ll “Disney-fy it a little bit.”) Even the outside predators are not so bad. Hutton, as the architect, is not typecast as an uncaring pencil-pusher who wants to bulldoze the beach, but as a wage-earner who moves from one job to another, living in motels, without a family, always on assignment.

Sayles pulls another surprise. His characters are not unyielding. Consider the scene where Marly tells her father she’s had it with the motel. Consider the scene where her mother, an Audubon Society stalwart, observes that there might be an angle in selling bird lands and giving the money to the society. Consider Eunice’s need to reconsider her daughter’s needs and behavior. Look at the daughter’s difficulty in reconciling memories of Flash Phillips with the car salesman she sees before her. And consider how at the end of the film, fate and history turn out to play a greater role than any of the great plans.

Sayles’ film moves among a large population of characters with grace, humor and a forgiving irony. The performances by Angela Bassett, Edie Falco and Mary Alice are at the heart of the story, and there are moments when other characters can illuminate themselves with one flash of dialogue, as Ralph Waite does one day in considering the future of the motel. Some of the characters seem to have drifted in from Altman Land, especially Mary Steenburgen’s, whose narration of the pageant is a wildly irrelevant counterpoint to the island’s reality. Others, like Tim Hutton’s sad architect, seem to have much more power than they do. And what about Alan King and his golfing buddies? They show that if you have enough money and power, you don’t need to get your hands dirty making more (others will do that for you), and you can be genial and philosophical–a sweet, colorful character, subsidized by the unhappiness of others.

“Sunshine State” is not a radical attack on racism and big business, not a defense of the environment, not a hymn in favor of small communities over conglomerates. It is about the next generation of those issues and the people they involve. Racism has faded to the point where Eunice’s proud home on Lincoln Beach no longer makes the same statement. Big business is not monolithic but bumbling. The little motel is an eyesore. The young people who got out, like Desiree, have prospered. Those who stayed, like Marly, have been trapped. And the last scene of the film tells us, I think, that we should hesitate to embrace the future in this nation until we have sufficiently considered the past.