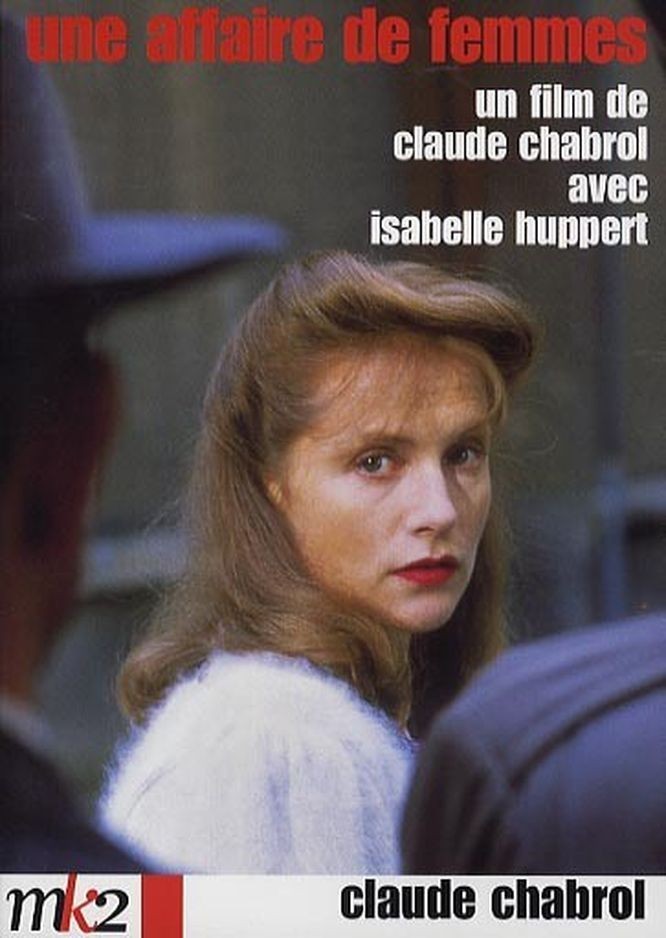

It is the unique ability of Isabelle Huppert to betray almost nothing to the camera, when she chooses to. Some of the best moments in her performances come when she regards the camera as if daring us to guess what she is thinking. This quality is indispensable to the character she plays in Claude Chabrol‘s “Story of Women,” because the story is based on the mystery of what she really thinks and feels.

The movie begins in 1941, in wartime France. Huppert plays Marie, a poor woman with a drunken nobody of a husband. The lives of herself and her two small children are wretched. One day she barges into a neighbor’s apartment and finds the woman trying to perform an abortion on herself. Marie knows a little about abortions – more than the neighbor, anyway – and assists her, using a different method. The abortion is successful, and the woman gives her a present – a record player. Listening to music on the player, Marie reflects that a clever woman need not be trapped by poverty.

The provincial French society around her looks thoroughly corrupt. Although a brave resistance is fighting somewhere, for many people the Nazi occupation has ushered in an era of collaboration and black-marketeering. Many of the men have gone off to take wartime jobs or even to fight for the Nazis. Most women, struggling to hold their families together in the face of poverty and the rationing of food and all consumer goods, have no desire for more babies. Yet wartime brings many pregnancies, some of them the result of liaisons while a woman’s husband is far away. There is money to be made in abortion.

Marie is the kind of person who reacts so directly to events that you can never say she has a plan. She stumbles into being an abortionist for two reasons: There is a demand, and she can use the money. She moves into a better apartment. There is more food for her children. As nearly as we can tell, she never gives a moment’s thought to whether what she is doing is right or wrong. It is illegal, but she doesn’t give that a moment’s thought, either.

One day she meets a former friend who seems to be doing well.

The woman is a prostitute. Marie is unconcerned. It is worth remembering that in many societies until fairly recent decades, the only ways a lower-class woman could support herself economically were as a servant, a laborer, a nun, an actress, or a prostitute.

Marie agrees to take care of any friends of the friend who may become pregnant. Clients materialize at her door. She moves into a still-larger place, begins to buy some luxuries for herself, and rents extra rooms to prostitutes.

Her husband is a problem. He makes no money and is generally useless, but he has his male pride, and Marie has no remaining sexual interest in him – she has taken a young collaborator as her lover. So she pays the maid to have an affair with her husband.

We begin to see her pattern. She does what is necessary to save herself trouble and keep her income out of jeopardy.

Eventually, the notoriety of her activities catches up with her.

She is arrested, and taken to Paris for a wartime show trial. Now her eyes are as blank as they were before. What does she feel? Guilt? Fear? Does she understand it will be necessary for the occupation government to make an example of her? Claude Chabrol is one of the most prolific of active directors; he has made more than 40 films, of a very wide range of quality, from masterpieces (“Le Boucher,” “This Man Must Die“) to whodunits and steamy melodramas. He is at his best where sex and crime intersect, and he is most fascinated with criminals who do not seem to relate emotionally to their own crimes (study the character of the murderer in “Le Boucher”). Huppert is the perfect actress for him.

The story he tells here, of a real woman named Marie Latour, is well known in France, where she was one of the last three women to receive the death penalty. The Latour case obviously fascinates Chabrol, perhaps because he does not know what her true motivations were. She began in poverty and was able to thrive and flourish under the Nazi occupation. She bought furs and kept a lover. She was not a “liberated woman” in any sense, and did not see her role as an abortionist as a brave or necessary one, but simply as a profitable and even inevitable route to a larger income.

Nor did the government really see her as a criminal. The prosecution in the film is shown as devoid of moral outrage, but obsessed by the need to “set an example.” The whole episode seems to have unfolded without anyone really feeling much of anything – anyone except for the family of a desperate mother of six who dies after one of Marie’s abortions.

Today the collaborationist government is reviled in France, abortion is legal and paid for by the government, and Marie Latour is dead. What is Chabrol’s message? He does not say. His film is as opaque as his character. “Story of Women” is a morality play without a conclusion. We have to make up our own minds. Most movies on themes like this instruct us about how to think, by portraying its characters as good or bad, and casting them to seem attractive or otherwise.

Chabrol does not make it so easy.