Families create their own narratives. Stories are passed on from generation to generation, and in this way the past continues to live, but it can also be obscured or distorted. Joan Didion famously wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Family arguments often come down to who “owns” the narrative, or which version is decided upon as the “true” one. Sarah Polley‘s fascinating documentary, “Stories We Tell,” is ostensibly about her mother, Diane Polley, who died in 1990. A powerful and thoughtful film, it is also not what it at first seems, which is part of the point Polley appears to be interested in making. Can the truth ever actually be known about anything?

In speaking about “Stories We Tell,” it is important to avoid revealing the surprises hidden within the film, surprises of fact and surprises of Polley’s structure, because the discovery of said surprises is where the film packs its greatest and most indelible punch. The surprises do not operate as cheap “Gotcha” moments, but instead draw back veils to show levels, shades, nuances. Diane Polley comes to us in fragments, and we are forced to re-adjust our interpretation of her throughout the film as new details are revealed. At one point, one of Polley’s interview subjects balks at the idea of having everyone tell the same story. As far as he is concerned, only two people have the “right” to tell that story, and it is the two people involved. Otherwise, he says, “you can’t ever touch bottom.” Inadvertently, in his criticism, he expresses Polley’s whole theme.

Polley calls her interview subjects “The Storytellers,” and they include her older sisters, Susy and Joanna, and her older brothers, John and Mark, and other important figures in her mother’s past. Polley has said she was not interested in being an “omniscient” presence, and we can hear Polley’s questions and laughter from behind the camera. Her father, Michael Polley, is an actor as well (familiar to anyone who was a fan of the Canadian TV series Slings and Arrows, where, incidentally, Sarah Polley had a role in the third season). “Stories We Tell” begins with Sarah setting up her father in a recording booth, to do the narration for the film, which (we find out later) he wrote. So there is already a distancing element in place. It’s a film about making a film, and, as Polley tells her father, she sees the interviews as a kind of “interrogation process.”

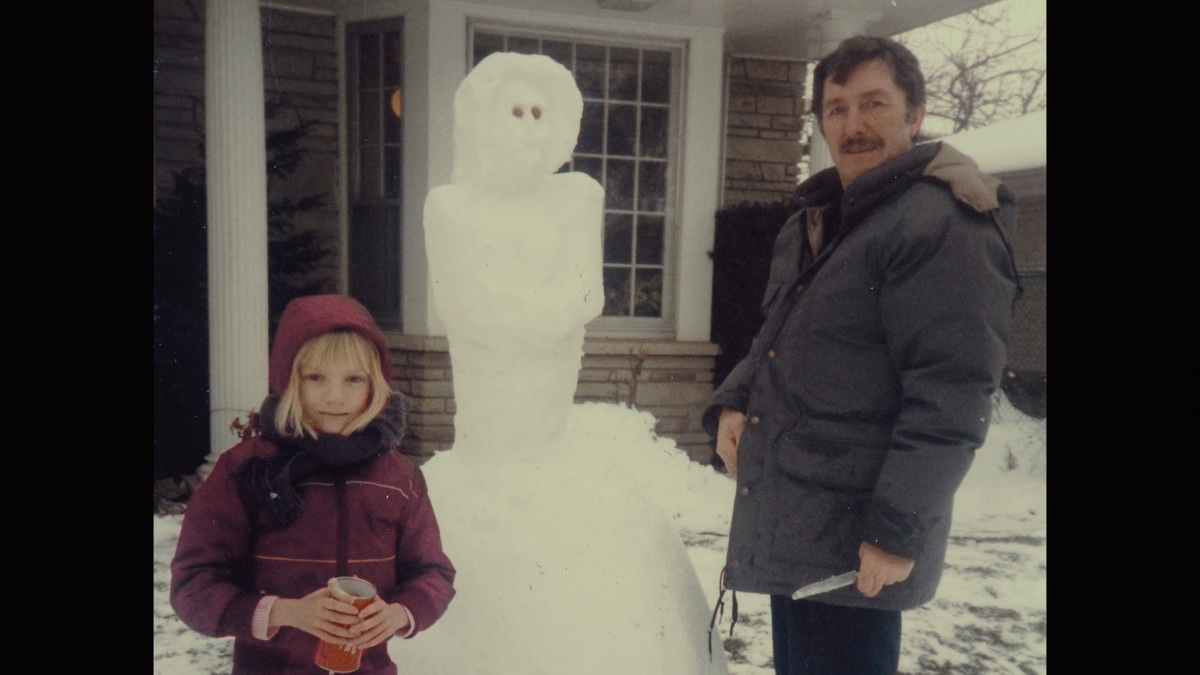

She asks each storyteller to “tell the story from the beginning until now,” and as they begin, hesitantly at first, Polley supplements the story with old photographs and home movies: beautiful footage of her mother, cavorting on the beach, laughing at parties or around the pool, and, fascinatingly, singing “Ain’t Misbehavin'” in what looks like an old black-and-white audition tape. Diane Polley is described by one and all as a woman who wanted to live life to the fullest. One person says that her walk was so emphatic “she made the record skip,” an eloquent image. One family friend admits in an interview that she always sensed that Diane “had secrets,” which turns out to be true. She was an actress, but she gave that up to have her family. The marriage to Michael was happy at first, but discontent grew. Michael was a solitary type of guy, and Diane loved crowds and excitement.

The storytellers talk about her life, her acting, her children and her marriage, and Polley doesn’t privilege one version over another. She is not interested in protecting her version (whatever it may be), or protecting her mother. She is more interested in how her family members interact with their own memories, and where they might intersect or diverge. Polley’s touch here is gentle and yet insistent. At times, her siblings ask her, speaking to her behind the camera, “Well, what do you remember about that time?”

Sarah Polley got her start young in Canadian television, but she showed a rebellious streak early, dropping out of acting altogether as a teenager to focus on politics. Her role in Atom Egoyan’s “The Sweet Hereafter” (1997) was hailed by American critics, who treated her as a newcomer (although she had been working for years in Canada by that point). Polley resisted the call of stardom, doing what interested her, and making short films through the Canadian Film Centre’s prestigious director’s program. Her first feature, “Away From Her,” was a heartbreaking tour de force, showing Polley’s breathtaking confidence as a first-time director. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards (Julie Christie as Best Actress, and Polley for her adaptation of Alice Munro’s short story). Polley’s second feature was 2011’s “Take This Waltz,” starring Michelle Williams and Luke Kirby (Kirby, like Polley, was treated as a newcomer by American critics, but he had been riveting in the first season of Slings and Arrows as the American movie star playing “Hamlet” in Canada).

In both of these films, and now in “Stories We Tell,” Polley experiments with the expected narrative structures, pushing us to consider not just the meaning of stories but how the way we tell the story can change its impact. The interviews in “Stories We Tell” are amazingly intimate. This is a family talking to each other. Everyone still misses Diane. The loss they have suffered is incalculable. The questions Polley asks are not always easy. The answers aren’t simple either.

Diane Polley was, in some respects, a trapped woman. It’s a common story with a common narrative thread, familiar to us all: she wanted more out of life than just being a mother and a wife, but she was hemmed in by traditional responsibilities. But life is not that simple, and when you learn more about Diane, when you learn some of those “secrets,” and one in particular, the cliched narrative thread falls apart. Diane Polley seemed to be an extroverted fun-loving person, and she was, and yet obviously the well was deep (so deep you “can’t reach bottom”). Life is messy and Diane Polley’s narrative is messy. Stories told again and again have a way of neatening things up. Stories have a way of ironing out the wrinkles. Polley lets the wrinkles remain. By the end of “Stories We Tell,” I am left with the feeling that there’s still so much I don’t know about Diane Polley. And what a fitting eulogy that is.