If I were to describe the plot of “Square Dance,” you’d likely laugh out loud. The movie itself denies even that pleasure. This is a weary morality play that sinks under the weight of its good intentions.

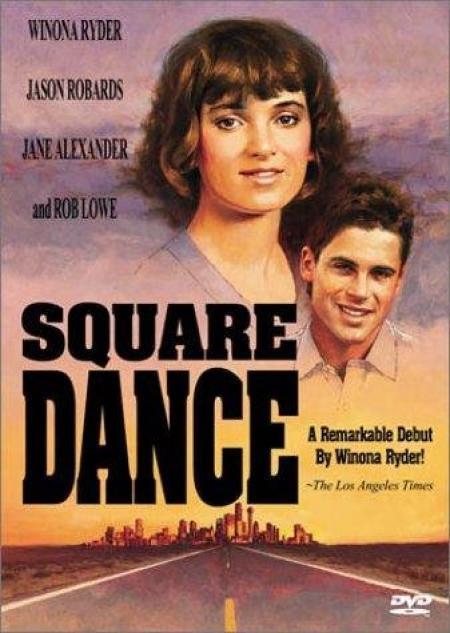

The story involves a group of small-town people who have an amazing number of unlikely things happen to them and it struggles to carry the burden of Meaning and Significance that lurks beneath every development. What this movie needs is something to break the ice, maybe something like the projectile vomiting scene in “Stand By Me.” The story begins down on the farm, where Jason Robards‘ character is a stern taskmaster for his granddaughter, Gemma (Winona Ryder).

Seems like the girl can’t do nothing right. And yet there’s still a spark of humanity in the old codger, as when he remembers the grand days when they all used to square dance.

One day, a visitor arrives at the farm and surprises Gemma. It’s Juanelle (Jane Alexander), her mother, who ran off to the big city more than a dozen years ago, and left her daughter to be raised by Robards.

Deep secrets surround the identity of Gemma’s father, and there are a lot of skeletons in the family closet. Juanelle utters some hapless dialogue about doing what she had to do, and returns to the city, where she lives over the gas station with a man who dislikes it when she drinks too much and flirts with the guys at the bar.

Before long, Gemma takes a bus to the city to follow her momma and get to know her better. Juanelle is none too pleased. But before long, Gemma begins to fancy Rory (Rob Lowe), the good-looking son of the beautician across the highway. He is mentally retarded. Some of the kids make fun of him. Gemma likes him. This sets up a cruel practical joke in which their hearts are broken through a tragic misunderstanding. Meanwhile, things get to seem a little crowded up above the gas station, so eventually Gemma goes back home, after which there is sort of a happy ending, and certain questions are answered while others remain a mystery.

Students of square-dancing will know that “home” is the position where all of the partners end up exactly where they started out. If you can understand that concept, not only can you understand the symbolism of this movie, but you also have mastered it.

No amount of symbolic analysis, however, will explain (1) what they were thinking of when they created the Jason Robards character, so mean and mysterious, (2) what it proves when Gemma goes to town, or, (3) what it proves when she leaves town, or, (4) why anyone thought the movie fans of America were eager to see Rob Lowe play a mentally retarded kid, especially in a movie that reveals no particular familiarity with mental retardation.

In the 1950s, when a movie like this might have passed for being psychologically significant, there would have been some sort of payoff, some sort of breakthrough. But these days, simple human behavior seems to be enough; this movie introduces its characters, they go through some experiences, and then the movie ends, with all of the characters sadder but wiser, and the audience just sadder.