Well-timed to open soon after genome pioneer Craig Venter’s announcement of a self-replicating cell, here’s a halfway serious science-fiction movie about two researchers who slip some human DNA into a cloning experiment, and end up with a unexpected outcome or a child or a monster, take your pick. The script blends human psychology with scientific speculation and has genuine interest until it goes on autopilot with one of the chase scenes Hollywood now permits few films to end without.

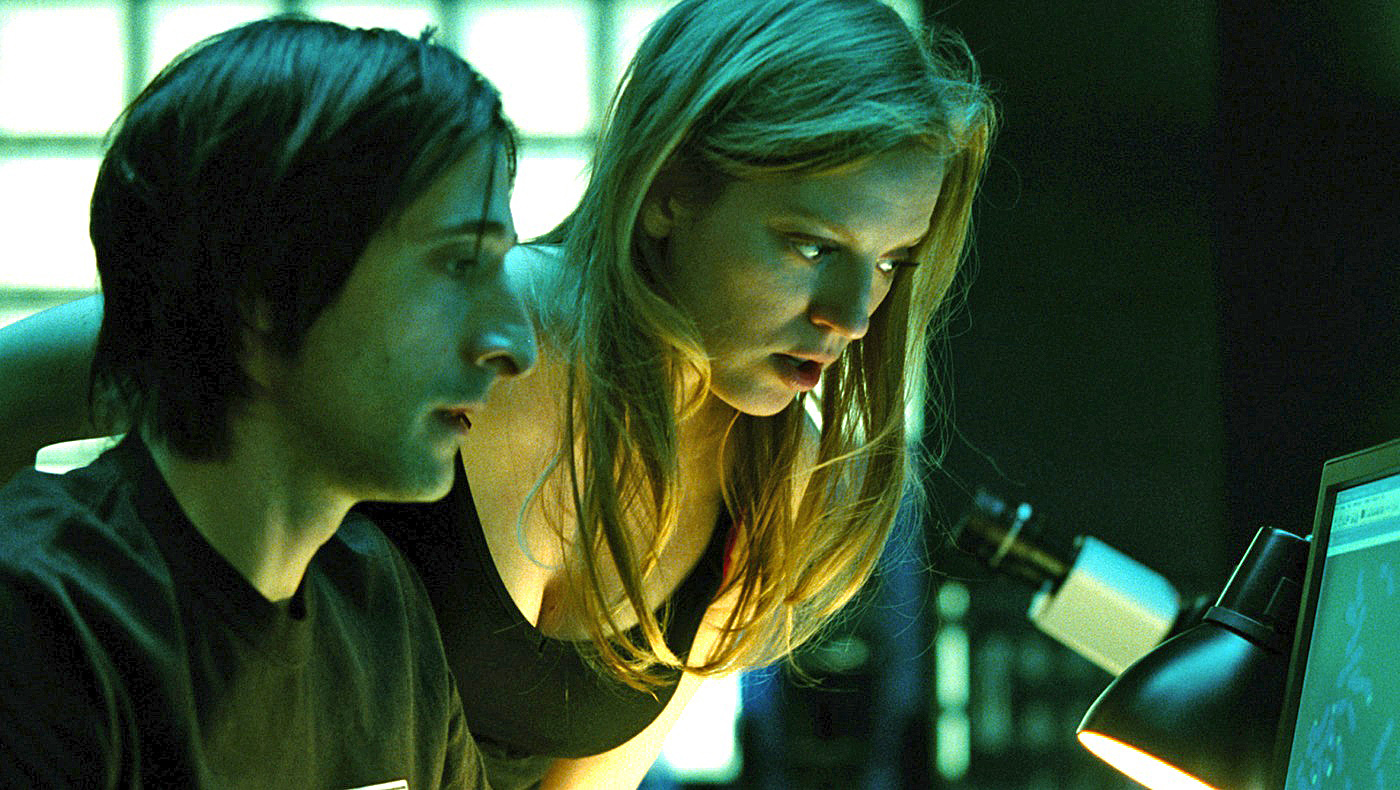

In the laboratory of a genetic science corporation, we meet Clive and Elsa (Adrien Brody and Sarah Polley), partners at work and in romance, who are trying to create a hybrid animal gene that would, I dunno, maybe provide protein while sidestepping the nuisance of having it be an animal first. Against all odds, their experiment works. They want to push ahead, but the corporation has funded quite enough research for the time being and can’t wait to bring the “product” to market.

Elsa rebels and slips some human DNA into their lab work. What results is a new form of life, part animal, part human, looking at first like a rounded SpongeBob and then later like a cute kid on Pandora, but shorter and not blue. This creature grows at an astonishing rate, gets smart in a hurry and is soon spelling out words on a Scrabble board without apparently having paused at the intermediate steps of learning to read and write.

Clive thinks they should terminate it. Elsa says no. As the blob grows more humanoid, they become its default parents, and she names it Dren, which is nerd spelled backward, so don’t name your kid that.

Dren has a tail and wings of unspecific animal origin, and hands with three fingers, suggesting a few sloth genes, although Dren is hyperactive. She has the ability common to small monkeys and CGI effects of being able to leap at dizzying speeds around a room. She’s sweet when she gets a dolly to play with, but don’t get her frustrated.

The researchers keep Dren a secret, both because they ignored orders by creating her, and because, though Elsa didn’t want children, they begin to feel like Dren’s parents. This feeling doesn’t extend so far as to allow her to live with them in the house. They lock her in the barn, which seems harsh treatment for the most important achievement of modern biological science.

Dren is all special effects in early scenes, and then quickly grows into a form played by Abigail Chu when small and Delphine Chaneac when larger. She also evolves more attractive features, based on the Spielberg discovery in “E.T.” that wide-set eyes are attractive. She doesn’t look quite human, but as she grows to teenage size she could possibly be the offspring of Jake and Neytiri, although not blue.

Brody and Polley are smart actors, and the director, Vincenzo Natali, is smart, too; do you remember his “The Cube” (1997), with subjects trapped in a nightmarish experimental maze? This film, written by Natali with Antoinette Terry Bryant and Douglas Taylor, has the beginnings of a lot of ideas, including the love that observably exists between humans and some animals. It questions what “human” means, and suggests it’s defined more by mind than body. It opens the controversy over the claims of some corporations to patent the genes of life. It deals with the divide between hard science and marketable science.

I wish Dren’s persona had been more fully developed. What does she think? What does she feel? There has never been another life form like her. The movie stays resolutely outside, viewing her as a distant creature. Her “parents” relate mostly to her memetic behavior. Does it reflect her true nature? How does she feel about being locked in the barn? Does she “misbehave,” or is that her nature?

The film, alas, stays resolutely concerned with human problems. The relationship. The corporation. The preordained climax. Another recent film, “Ricky,” was about the French parents of a child who could fly. It also provided few insights into the child, but then Ricky was mentally as young as his age, and the ending was gratifyingly ambiguous. Not so with Dren. Disappointing then, that the movie introduces such an extraordinary living being and focuses mostly on those around her. All the same, it’s well done, and intriguing.