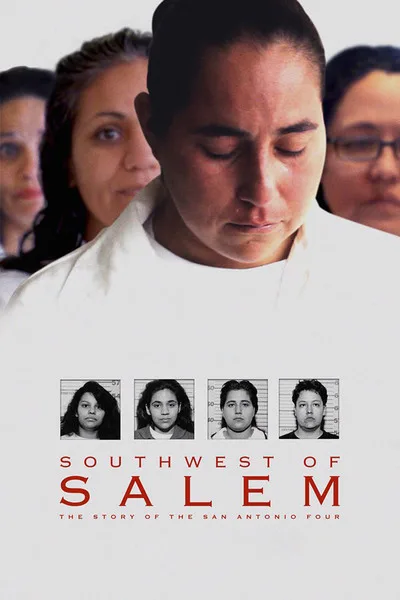

“[The San Antonio Four] case represents the last gasp of the Satanic Ritual Abuse panic.” The quote comes from Debbie Nathan, an interview subject in Deborah S. Esquenazi’s documentary “Southwest of Salem.” The documentary details the case of the “San Antonio Four,” where four Latina lesbians were accused in 1994 of gang-raping two little girls. The trials followed a couple of years later, and none of the women took plea bargains; all maintained their innocence and all were given lengthy prison sentences. Debbie Nathan co-wrote a book in 1995 debunking SRA (“Satanic ritual abuse”), that bizarre hysteria that swept the nation in the 1980s, a hysteria which got serious coverage in the news at the time (as though it was a real thing), and impacted law enforcement procedures, childcare and pediatric institutions, as well as therapeutic practices like “recovered memories,” designed to help children “recover” memories of their abuse. The “San Antonio Four” did not receive much (if any) national media coverage. Esquenazi became interested in the case years ago, and reached out to Debbie Nathan, who had also been a researcher and interview subject in Andrew Jarecki’s 2003 documentary “Capturing the Friedmans,” another case that erupted out of the SRA panic. “Southwest of Salem,” featuring prison interviews with all four women, is an urgent and often infuriating documentary about the San Antonio Four’s quest for justice and exoneration, a quest that remains ongoing.

Anna Vasquez, Cassandra Rivera, Kristie Mayhugh and Elizabeth Ramirez all came from strict Catholic homes, and grew up in a conservative Texas environment. “Coming out” was stepping into an unknown world, with perhaps terrifying consequences. Anna Vasquez came out to her mother when she was still in high school. Her mother went to talk to her priest about it and asked him what she should do about her daughter. He said, essentially, “Love her.” And so she did. Some of the other girls didn’t have it so lucky. They were thrown out of their homes, disowned. Anna and Cassie, a young woman with two children, fell in love. Kristie and Elizabeth made up the larger posse, and the women were friends, helping one another, being there for one another. For years all was well, until one day, after taking care of two of Elizabeth’s young nieces, the four women were accused of sexual assault.

There was no physical evidence that a crime had taken place. Although the four women insisted that nothing had happened, in an environment of hysteria, homophobia and credulity, they didn’t stand a chance. There was sketchy evidence from a pediatrician (debunked later), as well as the testimony of the two little girls, testimony that sounded fantastical, beggaring belief. Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, Javier Limon, father to the two accusers, had been pursuing Elizabeth romantically, and was angry that she rejected his advances. Couldn’t it be possible that he had coerced his children to make up a story so he could “get even” with the woman who dared to prefer women over him? But there wasn’t a lot of critical thinking going on, and—understandably—nobody wants to disbelieve children when they make an accusation like that. The womens’ homosexuality was used against them in their trials, and the news coverage was quite literally hysterical: the women were clearly witches, the children were “sacrificed on the altar of lust” (an actual headline).

Esquenazi presents all of this complicated information in a straightforward and compelling way, using local news footage, home movie footage, and prison interviews with the four co-defendants. Anna is the main interview subject, and she can still barely speak of what happened without weeping. Elizabeth is devastated that her nieces, whom she took care of all the time, would betray her, but she knew they had been coached by her vindictive brother-in-law. Anna refused to go into the Sex Offender program in prison, jeopardizing her possibility of parole, and causing her to lose any prison privileges she might have gained. Esquenazi also interviews the sheriff, the Mayor, the lawyers, many of whom betray their prejudices right to the camera, seemingly not realizing that they are doing so. The one unsatisfying interview is with Javier, who claims that nothing Elizabeth says is true. As more and more information comes out, one wishes that Esquenazi would return to that interview, ask some tougher questions, push him to go deeper, explain himself. What is his relationship like with his daughters, the original accusers, now? There are many unanswered questions.

The “San Antonio Four” do not have the brand-name recognition of the West Memphis Three although the cases share a lot of similarities. Viewers may get flashbacks to Joe Berlinger’s “Paradise Lost” documentary series, another case—occurring at the same moment in time—borne out of the Satanic Ritual Abuse panic where innocent people, perceived as “different” by the communities in which they lived, were accused and convicted of horrible crimes.

Despite the lack of media attention, the San Antonio Four caught the eye of a researcher who lives in the Yukon Territory, of all places. He was outraged by what he saw and began a campaign to get their cases re-opened. This was how Debbie Nathan got involved, and that eventually led to the famed Innocence Project (the Lubbock chapter) becoming interested in a re-investigation of the evidence. One of the accusers, now in her 20s, re-canted her original story, saying she and her sister had been coached by their father and their grandmother on what to say. The four women want complete exoneration. They do not want to have to register as sex offenders when they are released. They want the record wiped clean.

Similar to the first and second installments of “Paradise Lost,” “Southwest of Salem” is a story that has not found its ending yet. Like Truman Capote, waiting to see what would happen to murderers Dick Hickock and Perry Smith, for months, years, knowing he needed some definitive outcome in order to finish his book “In Cold Blood,” Esquenazi has watched and waited and filmed, following the course of the case. Her documentary footage represents years of work, and it’s an extremely impressive archive (a shoutout must be given to the talented editors, Leah Marino and Liz Perlman).

“Southwest of Salem” has an investigative questioning bent, but it is always clear in its attitudes about the four co-defendants. It is a powerful act of advocacy. It’s hard to look at these events in any light other than that a terrible miscarriage of justice has taken place.