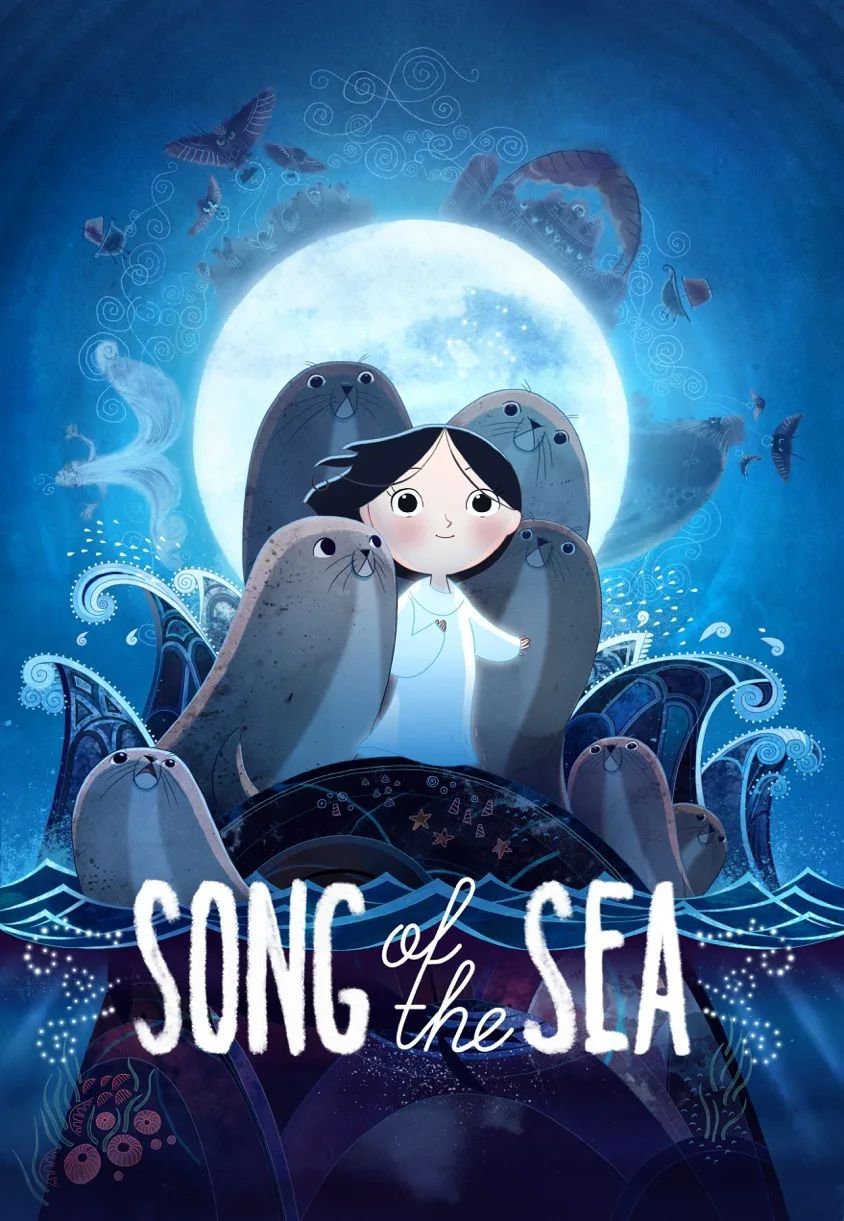

Visually splendid, but generically flat-footed, “Song of the Sea” is an animated fantasy that comes close to greatness, but is rarely as clever as it is comforting. Like “The Secret of Kells,” director Tomm Moore’s previous film, “Song of the Sea,” an Irish children’s story about a boy’s quest to heal his ailing sister, has a beautiful visual style. CGI-imagery subtly enhances hand-drawn animation, giving the film a singularly modern look. Moreover, Moore conveys a lot with a little; he prefers to let his characters’ richly-detailed environments, and nuanced body language speak for them.

“Song of the Sea” is, in that sense a quiet film, but its serenity doesn’t completely make up for its formulaic narrative. This is especially disappointing since Moore and screenwriter Will Collins try to avoid several clichés, like when Ben (David Rawle) confronts Macha (Fionnula Flanagan), an antagonistic Celtic goddess, and doesn’t try to beat her up, but rather to reason with her. Unfortunately, too much “Song of the Sea” feels like it was borrowed from other fairy tales, making Moore’s sophomore feature a warmed-over tale told with infectious flair.

A good part of what’s wrong with “Song of the Sea” is its dual dependence on Ben’s curiosity and his sister Saoirse’s (Lucy O’Connell) illness. After their mother’s mysterious disappearance, Ben and Saoirse take care of themselves while distraught father Conor (Brendan Gleeson) mourns privately. Because Conor’s mind is prone to wandering, he doesn’t believe, or even notice when Ben discovers that Saoirse is a selkie, a human changeling that can transform into a seal. So while it’s up to Saoirse to find her voice, it’s up to Ben to protect Saoirse when she falls ill, and cannot fend for herself. Ben’s adventure was foretold by a prophecy, of course: Saoirse’s fate is sealed if she doesn’t sing, thereby freeing other fairy sprites from Macha, a malevolent deity who steals fairies’ emotions, and turns them to stone.

The Celtic traditions that Moore tries to both honor and enliven in “Song of the Sea” are exciting, but they often feel like negligible grace notes in an otherwise familiar melody. The worst example of this is when three fairies try to explain to Ben what fairies are, and wind up learning more from him then he does from them. While that reversed power dynamic is clever, and unexpected, it doesn’t change how dramatically inert the scene is. This is a major problem since the film’s connect-the-dots narrative is the context that should make the film’s folk songs, and fairy tale characters exciting. Bruno Coulais’s score is moving, and Ben’s eccentric fairy guides are charming enough. But because Ben never really goes anywhere unexpected, the film’s mythical archetypes don’t feel deservedly grand.

Likewise, Moore (he wrote the film’s story) and Collins’s flimsy scenario also short-changes several genuinely moving scenes. “Song of the Sea” eventually coalesces into a story about grieving and coping with loss, but the film never really recovers from its doughy second act. And without a strong dramatic cohesiveness to carry the film from small gestures to big emotions, the little grace notes that make “Song of the Sea” valuable become that much harder to hear.

Thankfully, what Moore gets right generally outweighs what he gets wrong. The eccentric, moving-storybook look and gentle pacing of “Song of the Sea” make up for a lot of the film’s short-comings. And the film’s voice cast are all rather good, particularly Flannagan, and Rawle, both of whom carry the film through its relatively heavy third act. Flawed as it is, “Song of the Sea” is also genuinely kind, and never so cynical that it tries to wave away its imaginative failings with bad meta-jokes, or cheesy twists. It was clearly made by people who aspire to make smarter, and more fulfilling children’s’ films, stuff that will stay with viewers, and leave them better for it. In that sense, “Song of the Sea” is exactly the kind of animated movie I wish was made more often.