The two brothers who are the heroes of Kevin Jordan’s “Smiling Fish and Goat on Fire” are not Native Americans, but their grandmother was half Indian, and she nicknamed them–Tony is Smiling Fish because he floats in the current, grinning, waiting for the world to drift his way. Chris is Goat on Fire because he wants to get everything exactly right. Chris is an accountant and Tony is an actor, which is the Los Angeles word for unemployed.

In their 20s, they live in the cozy bungalow left them by their parents (whose marriage had an L.A.-style entrance and exit; they met on the Universal Studios tour and died in a traffic accident). Tony and Chris both have girlfriends, but we sense that one relationship is dying and the other looks ominous since the girl cries a lot during sex. And then their lives take a turn for the better with the introduction of two women, a 6-year-old girl, a 90-year-old man, and a chicken named Bob.

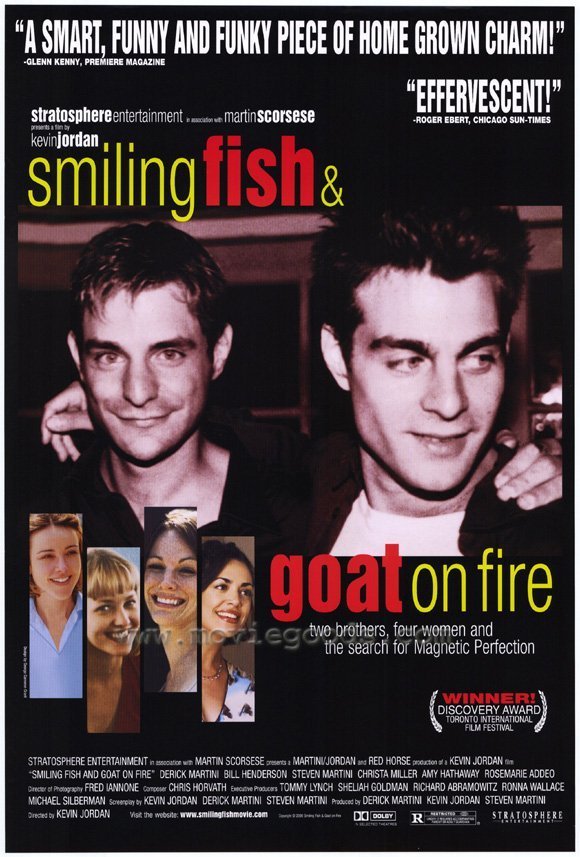

Chris (Derick Martini) meets Anna (Rosemarie Addeo), an Italian who works on movies as an animal wrangler. Bob is her chicken. Tony meets his postal carrier, Kathy (Christa Miller), who is from Wyoming and has moved to L.A. in hopes that her daughter Nicole (Heather Jae Marie) will find work as a child actress. Kathy’s heart is more or less stolen by Tony when he silences the squeaking wheel on her mail cart with olive oil.

Our hearts, meanwhile, are warmed by the introduction of a character named Clive (Bill Henderson), who is the 90-year-old uncle of Chris’ boss. The boss asks Chris to give Clive a ride to work, and Clive turns out to be a bottomless well of entertainment and wisdom for Chris and Tony, and for us.

He used to work as a sound boom man on African-American movies, Clive says. He met Rebecca, the love of his life, on a Paul Robeson picture. At work, he erects a tent over his cubicle, moves a friendly desk lamp under it, and listens to jazz. The character could steal the movie, but generously shares it with the stories of the brothers and their new loves and leftover problems with the old loves.

“Smiling Fish and Goat on Fire” is one of those hand-made movies that sneaks into festivals and wins friends. I saw it on the final weekend of the 1999 Toronto Film Festival, where Henderson (who is nowhere near 90) got a standing ovation. Talking to the filmmakers, I learned that director Jordan and the Martini brothers, who co-wrote the screenplay, were longtime friends, that the movie cost $40,000 and that it was shot in the brothers’ actual house. (There is an echo here of a past Sundance winner, “The Brothers McMullen,” also shot in its director’s home.) Many other movies costing $40,000 (and less, and more) have gone into to deserved oblivion, but “Smiling Fish and Goat on Fire” has a freshness and charm, a winning way with its not terrifically original material. The movie isn’t really about a plot, but about developments in the lives of characters we like. When a standard plot element develops (a possible pregnancy, for example), the movie uses it not for a phony narrative crisis, but for understated human comedy. By not trying too hard, by not pushing for opportunities to manipulate, the movie sneaks up and makes friends.

The brothers Martini are effortlessly likable and convincing in the film, which we feel is close to their personalities if not to the facts of their lives. As for Henderson, I hope casting directors see him here and use him. He has been in a lot of movies (he was the no-nonsense cook in “City Slickers“), but this movie suggests new ways he could be used; it gives him notes we want to hear again. And the way he evokes the lost world of the African-American film industry is like a film within the film; the way he evokes his love for Rebecca, glimpsed only in old photos, is surprisingly moving.