A middle-aged white man stands on an outdoor stage, addressing an enthusiastic audience, whipping his followers into a frenzy. He says he plans to run for the Ohio state legislature, and his disparagement of Asians, blacks and other minorities (although he uses far more offensive language to describe them) is the central premise of his platform.

“Maybe we should just make them leave,” he suggests forcefully, and he’s greeted with wild cheers of agreement in response.

It’s a chilling echo of the kind of “Send her back” chants we’ve heard at a recent presidential rally and seen on Twitter. But it takes place during an early scene in “Skin,” and it’s set more than a decade ago. The drama, inspired by the true story of a young man who dared to escape his white supremacist group and remove his many racist tattoos, sadly couldn’t be more relevant. Bryon Widner fled the violence and hate that defined his life for so long, but they aren’t going anywhere.

Writer/director Guy Nattiv’s film isn’t exactly a feature-length version of his Oscar-winning, live-action short, although it happens to carry the same title. Both films depict clashes between white supremacist gangs and black activists and both feature “Patti Cake$” star Danielle Macdonald in a crucial role. And both explore in unflinching fashion what it means to wear your beliefs outwardly in such brash fashion—the intimidation factor such imagery creates, and the vow of loyalty it suggests.

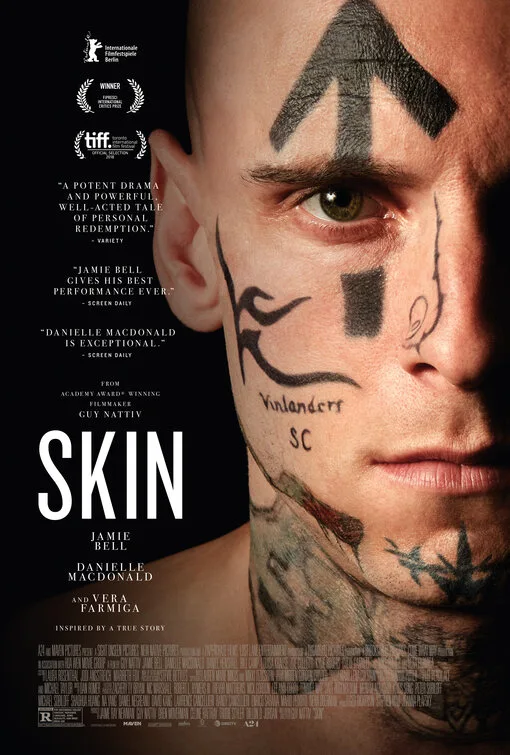

This “Skin” focuses on Widner and how his allegiance to the Vinlanders Social Club, in which he was a key figure of authority, began to waver. (His story already has been the subject of the 2011 documentary “Erasing Hate.”) And in a stunningly transformational performance, Jamie Bell is nearly unrecognizable as Widner. Bulked up and covered in a smattering of white power tattoos—many of them on his face and neck—Bell carries himself with a fearsome swagger, which makes his moments of kindness and decency that much more striking by comparison. Bell gets the opportunity to show huge emotional and physical range here, and even when the script turns a bit melodramatic toward the end, he provides a secure through-line.

Nattiv alternates between Widner’s gradual questioning of his hateful beliefs and deeds and the grueling removal of his tattoos, a lengthy process he must undergo in order to start a new life. Handheld camerawork, close-ups of volatile behavior and a general grunginess give these flashbacks a feeling of tension and a vivid sense of place; the more recent shots of the medical procedures he endured are crisper, glossier and more detached, creating the sensation of wiping a slate clean.

Portraying Widner with depth and complexity is a fascinating and necessary decision, although one that’s sure to rile some viewers. Despite his abhorrent acts, he’s not purely evil. He can be loving and tender, especially with his beloved Rottweiler and the three daughters of his girlfriend, Julie (Macdonald), who show him what being a part of a real family can feel like. On the flip side of that are Bill Camp and Vera Farmiga as Fred and Shareen Krager, the gang’s leaders, who sickeningly use the notion of family to lure in the lost and lonely kids they see on the streets. They insist that their followers call them Dad and Mom, and while they’re unified in purpose, they employ slightly different tactics to pounce on their prey. Fred—who’s riling up the troops with his speech at the film’s start—exudes a manly-man form of tough love, and he’s hardcore in his twisted take on Viking brotherhood and honor. Shareen’s a charmer, seducing Julie’s eldest daughter, the teenage Desiree (Zoe Colletti), with compliments and cutesy names like “doll” and “precious.” With her conniving ways, her calculating use of maternal warmth and a calm demeanor in even the tensest situations, Farmiga is deeply unsettling.

As Widner begins to see the light and seeks to change his ways with the help of activist Daryle Jenkins (Mike Colter of “Luke Cage”), he naturally finds himself in increasing danger. Even going along on a middle-of-the-night mission to burn down a mosque isn’t enough to convince his fellow Vinlanders that he’s still fully on board. Bell makes Widner’s doubt and pain palpable, as is the frustration he feels as he struggles to start over. Hope is tantalizing, elusive. But what “Skin” optimistically suggests is that if someone so deeply entrenched in hatred can turn his life around, maybe there is indeed hope for others. It’s a nice idea.