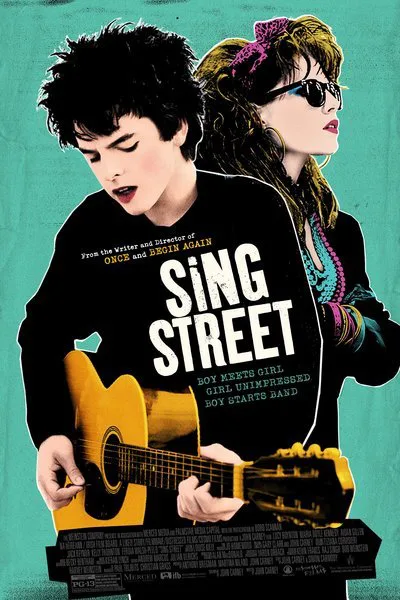

Writer/director John Carney, who directed the award-winning Irish musical “Once“, returns to familiar territory with “Sing Street”, peppered with musical numbers, and in love with what music can unleash in its characters and audience. A song can “take you back” to specific moments in time, connecting you to a younger self, memories and dreams in a continuum. “Sing Street” takes place in Dublin, 1985. The so-called Celtic Tiger is years in the future, and prospects for Irish kids look bleak. In the opening sequences, the Irish are shown emigrating to London in droves, seeking work and a hopeful future. That moment-in-time backdrop is essential to the wonderful “Sing Street”, a movie about escape, identity, dreams vs. reality, young love, and music (and because this is 1985, it’s also about that new-fangled mind-blowing innovation called a “music video.”) John Carney has a humorous and loving eye for detail, an intuitive ear for dialogue, and the film is extremely personal in a way that is universal.

There are pitfalls everywhere in a coming-of-age period piece like this one, but Carney avoids them easily, keeping the film on its proper track. It’s extremely confident: It knows what it wants to be, what story it wants to tell. While “Sing Street” is often hilarious (in a darkly honest Irish way), it’s also so full of heart that by the end you’ve seen a film where dreams really do mean something, where escape hatches exist, you just have to be bold enough and imaginative enough to take a chance. Taking a chance in “Sing Street” means various things: starting up a band even though you don’t play an instrument, wearing makeup even though you’re a boy, walking across the street to talk to that pretty denim-clad girl you see every day on your way to school. “Sing Street” never condescends to the yearnings, pain, and hopes of its main character, teenage boy Conor (played by Ferdia Walsh-Peelo, so hugely talented it’s hard to believe “Sing Street” is his debut), and, even better, believes in the dreams of every character in the film, even minor ones.

The home life of Conor and his two siblings is not Dickensian by any means, but the vicious fights of their parents (played by Aidan Gillen and Maria Doyle Kennedy, both great in small roles) makes the tail-end of their childhoods like a prison sentence. Each sibling seeks escape from the household tension in their own ways. Older brother Brendan (Jack Reynor, a standout talent central to the film’s success) holes up in his room with his weed and his impressive record collection. Older sister Ann (Kelly Thornton) devotes herself to her studies. Conor is lost in the shuffle after being yanked out of private school and tossed into the Synge Street public school, which is like throwing fresh meat to lions. The student body and the priests at Synge Street are so rough that the movie feels like it takes place in a maximum-security prison for the criminally insane. Conor picks up his own personal bully immediately, as well as a scrawny red-headed sidekick.

At home, Conor and Brendan sit on the couch, watching music videos, Duran Duran pretty boys dominating. Conor can barely process the awesome-ness of what he sees, and Brendan takes on a mentor role, pontificating on the music business. Brendan is sunk in some lost dreams of his own, and one of his self-appointed roles in life is to teach his little brother the ropes. (“Sing Street” is extremely accurate about the relationship between close siblings.) Conor, inspired, decides to start a band. He kind of sort of plays the guitar, and he’s innocent enough to believe that his music might get him to England, like Duran Duran. He also thinks it might make him seem cool to Raphina (Lucy Boynton), the aforementioned intriguing denim-clad girl across the street. Successful careers have been started for less. (Johnny Carson once asked Fernando Lamas why he got into show business, and Lamas answered, “To meet broads.”)

Putting together the band has the naive enthusiasm reminiscent of the punk-rock girls in the 2013 Swedish film “We Are the Best!”. The bar for entering rock ‘n’ roll is pretty low; there are no entrance exams. Conor finds allies, one in particular with whom he forms a songwriting collaboration. Before they’ve found a gig, they decide to make a music video, and Conor asks Raphina to be in it. Shockingly (to him), she agrees.

And with that, “Sing Street” takes off. Dreams don’t always line up with reality, and everyone (parents, siblings, the beautiful and complicated Raphina) learn that hard lesson. But sometimes reality is the dream: when a songwriter stumbles on the “hook” of a song, when a band made up of misfit strangers suddenly coalesce into a team, when the girl you love looks at you and shows you who she is. Dreams are fleeting, but we are nothing without the “substance of things hoped for.” The band develops, from a synth-pop sound, to a New Wave-ish aesthetic, as they try to figure out who they are. There are so many memorable sequences, quiet moments of growing connection between Conor and Raphina, the band’s series of music videos, and a killer fight scene between Brendan and Conor. Brendan, watching his brother blossom, thinks maybe that he is about to be left behind. Who will he be without his role as dispenser-of-music history and provider of-courtship-tips to his little brother?

As funny as the film is, John Carney infuses scenes with a poignancy bordering on deep blue melancholy. He is helped in this by the sensitive performance of Walsh-Peelo, required to run the gamut of emotions: hurt, fear, ambition, growing pains, first romantic feelings, a sense that the world is even more painful and scary than he had realized. It’s a delight to watch the flickers of thought his eyes, his quiet listening face, the rising flush in his cheeks in moments of intensity. He’s beautifully open as an actor.

The surrounding cast is superb, both the broad stereotypes and the eccentric weirdos in the band. Adolescence is one of the most self-involved phases of life, and that’s as it should be. Kids develop their characters and try on different identities, looking for a good fit. (Conor goes from dressing like Simon LeBon to Morrissey, and you get the sense he’s just getting started.) One of the most essential elements of adolescence is finding like-minded friends: people who obsess about the same things, people who “get” you. Whether it be serious-jock baseball players (as in Richard Linklater’s “Everybody Wants Some!!”) or devoted music obsessives, it’s the same goal: Find your people, find your own tribe.

There are openly crowd-pleasing scenes, and in this case that’s not a criticism. The triumphs are satisfying, the barriers are frustrating and even heartbreaking, the sweeping connections, when they come, work on that primal level that gets underneath the skin, vibrates on a certain frequency. The film works so well that when Carney’s dedication comes on the screen right before the credits roll, it unleashes profound emotion because it’s the anchor of what the film has been about all along, something felt throughout, but not underlined or spoken. “Sing Street” has a good and generous heart, and it beats because of that dedication.