Too soon! Comma or not, the English-language title of Japanese writer/director Hirokazu Kore-eda often wrenching new family drama (winner of the Jury Prize at last year’s Cannes Film Festival) bears too distinct a resemblance to the name of 1987’s universally beloved Dudley Moore/Kirk Cameron starter. What’s next, Japan? A movie whose title translates into “Gone, With The Wind?”

Okay, that’s enough out of me. But in all seriousness, the not inapt but too on-the-nose English language title of “Soshite chichi ni naru” (which, Google Translate tells me, works out to something like “And I Will Be His Father”) is the worst thing about this movie. Kore-eda, whose pictures don’t exactly alternate between soulful, understated fantastic fables (“Afterlife,” “Air Doll”) and quiet family dramas (“Still Walking“), brings his trademark delicate but deliberate eye (and ear) to a really heartbreaking scenario. Six years into raising their only child Keita, whose birth left the young mother unable to have any more children, young couple Ryota and Midori are told that the child is not, in fact, theirs at all: that a hospital error switched two baby boys at birth. Soon the couple are meeting their biological child for the first time, along with the family that raised him.

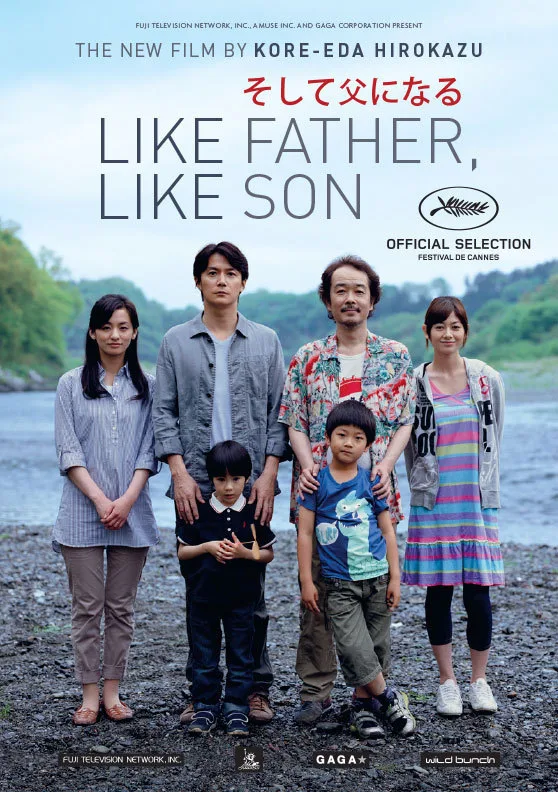

As would not be unexpected in a domestic melodrama, the two families could not be more different. While Ryota (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a cold-to-icy ambitious salaryman, next to whom Midori (Machiko Ono) sometimes looks resentfully dutiful, their biological son, named Ryusei, has been growing up with two young siblings, in a cozy raucous household whose tinkerer dad Yudai (Lily Franky) and ramen-restaurant-server mom Yukari (Yoko Maki) dote on their kids despite their limited means.

Initially the clash of classes seems a little schematic. The straightforward Yudai sees a big payoff from the hospital, while Ryota adopts an arguably fake-noble stance with his insistence that the money doesn’t matter, that they have to come up with a plan for what’s best for the kids. Obviously a swap has to be made, eventually. But is that conclusion really so obvious? In a series of beautifully calibrated scenes, Kore-eda explores not just the nature of parental love but of filial love, and as the painful alienated past of Ryota comes to light, his stiffness and lack of empathy become more comprehensible but no less kind of infuriating. It’s a testimony to Fukuyama’s acting skills that as pig-headedly alienating as the character can be, he never becomes a complete turn-off. That’s also a testimony to the way Kore-eda presents the situation; while the perspective is never not clear-headed, the abject heartbreak of the scenario is ever present. (Imagine the way that a typical Hollywood film about this story would make a deliberate burlesque of it.)

A second act plot twist of sorts doesn’t just accelerate the dramatic momentum; it forces the characters to confront the uglier sides of themselves. Every now and then, Kore-eda will overplay his representations a little bit; there’s a scene in which Ono’s character contemplates an escape from the torment of potentially trading the son she loves for a child she doesn’t know, biology or not; this takes place on a train, and as her thoughts grow darker, the shadows of the station that the train is pulling into throw her and the child actor into literal darkness. It’s a well-orchestrated effect that hinges on obvious. On the other hand, I suspect the only reason it stands out is because most of the movie is so subtle and straightforward. While I’m not a parent myself, I can see how “Like Father, Like Son” would be a tough sit for any parent. Tough, but extremely worthwhile.