“Seoul Searching” is one of the most personal films you’ll see in 2016. It starts with a voiceover from writer/director Benson Lee, who tells us about how after the Korean War, people like his parents left Korea “with a suitcase and a dream” for other countries, causing their children to have little idea decades later of their Korean heritage. In the 1980s, this new generation was brought back to South Korea to learn about their background at a coed summer school, which Lee attended. His big heart guides us through coming-of-age experiences both specific and universal, with a film that wants to be John Hughes-like (à la its “The Breakfast Club” poster) but can be parallel to Spike Lee’s “School Daze” in how it tackles race and identity with a burgeoning cinematic vision.

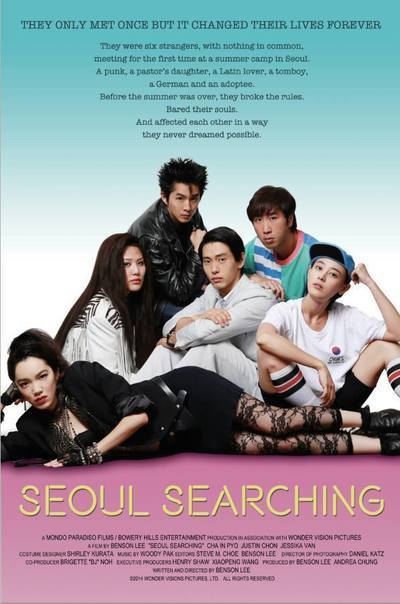

The initial hook of “Seoul Searching” is its most polarizing and brilliant artistic stroke. Its characters are dressed to their identities like uniforms, having an exaggerated presence. For example, Justin Chon’s Sid Park is the “Korean-American Punk,” dressed with a spiky hair, a reoccurring cigarette and a shredded Black Flag tee; Jessika Van’s Grace Park wears crucifix earrings, sunglasses and black tights, taking her background as a pastor’s daughter to the umpteenth Madonna level. Lee introduces these characters (a scene-stealing trio of RUN DMC lookalikes, Byul Kang’s tomboy, Teo Yoo’s German-Korean man and Esteban Ahn’s Latin-Korean man, among others) like runway models as they exit the airport terminal, captured with his constant wide angle lens to look larger than life. They create a mix of characters that pops just like the movie’s candy store color palette, illustrating the intense nature of identity.

What might seem like a visual gimmick during the film’s early, charming episodes of teen shenanigans (drinking, sneaking up to the girls’ quarters or out to clubs) soon establishes itself as high concept, especially as some of them confront the insecurities behind their daily costumes. The answer is often within their backgrounds, concerning their tension with their Korean-born parents, or the pressures within the social circles they cling to back home. With an exciting roster of young actors, the film’s performances match these images with full-body effect, like the way militarized Mike (Albert Kong) speaks, walks and sneers like a 50-year-old drill sergeant. A costume ball in the third act adds a beautiful poignancy, as the students all change their appearances to show how fluid identity can be, but that it starts with a personal choice. When Sid asks Mike about why he’s the way he is, he replies with a background of being the only Korean-American in his environment: “I have to be this way … I won’t survive otherwise.” “Seoul Searching” is unforgettable in how it boldly presents adolescence, specifically here from a minority’s perspective, not just as a life passage, but a type of performance.

What Lee does with these characters is always more inspired than it is tight, as it breaks off into different mini-arcs with Korea’s generational divide as his blanket statement. The schooling angle of the film leads to some direct conversations about what it means to be Korean, but the out-of-school dramatic moments touch upon something beyond history or language. Lee’s story often hits emotional climaxes with over-zealous waterworks, but his best story involves a young woman (whose “type” is that she’s adopted), who meets her biological Korean mother. In their two scenes, they can’t communicate with language, only through intense emotion—the daughter’s calm, mournful tone, responded to with a mother’s billowing, muted shame—creating an extraordinary and tender parent-child moment that is the best John Hughes-like quality of Lee’s film.

Coming directly from Lee’s perspective, the movie has a discouraging blind spot for half of its cast. For a story that often explores the cross-generational damage done by the standards of masculinity that Korean men can hold themselves to, “Seoul Searching” often introduces women with close-up butt shots, and later even gives Grace’s Madonna character an a cappella and dance performance of “Like a Virgin” with questionable agency. As Lee’s movie takes a huge stride away from horrifying Asian caricatures like Long Duk Dong in Hughes’ “Sixteen Candles,” the need for more progress remains obvious.

The episodic narrative of “Seoul Searching” can be too long and unfocused, but its stubbornness comes from filmmaking that is overflowing with self-pride. Lee says in the press notes that this film is “one that I’ve yearned to see all my life,” and that could be its entire plot synopsis. For people of whatever background or social designation, who will watch Lee’s movie and identify with new reflections of themselves, the power of that pride can never be underestimated.