Early in “Robin’s Wish,” a documentary about the life and death of Robin Williams, one of the actor’s friends speaks dismissively of the idea of the “sad clown” who’s laughing on the outside but crying on the inside. Coverage of Williams’ 2014 death fit the profile and then some.

The media narrative right afterward painted the 64-year-old actor and comedian as someone who had been struggling with drug problems and depression for most of his life, and ultimately succumbed to them. His demise sparked the standard arguments about the presumed “selfishness” of suicide, and raised the usual questions about whether his death could’ve been prevented had family and friends been paying closer attention to his struggles. This film gets into all that—”I felt remorse and guilt,” a neighbor tells the filmmakers. “I could have done more. I should have done more.” And Williams did suffer from chronic depression and substance abuse problems over the decades.

But all that turned out to be tangential: during his final year, Williams suffered from Lewy body dementia, a painful neurological disorder. The physical and mental suffering (which included insomnia, depression, and cognitive decline) baffled him and those close to him, and eventually pushed him over the brink.

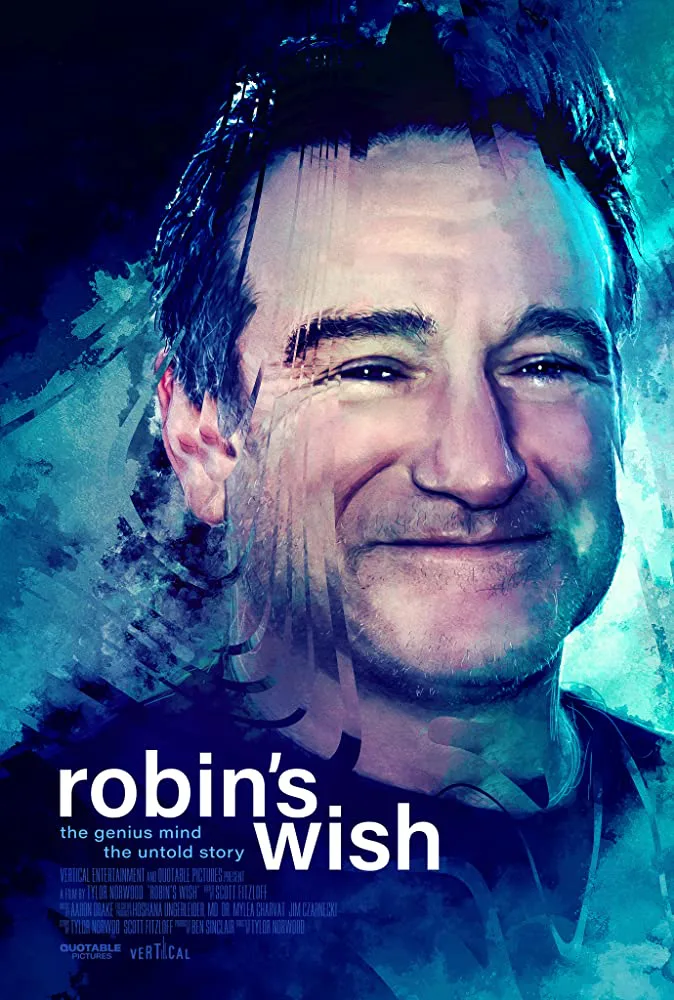

The movie does a conscientious though far from inspired job of illuminating the wider context of Williams’ end. Directed by cinematographer Tylor Norwood, this film is of limited use as a biography of the entertainer, and even though the project wasn’t meant to fulfill that mandate, it’s still frustrating how little insight it gives into Williams’ brilliance. Millions loved him from the second he burst into stardom on “Mork and Mindy.” His career continued to evolve after that, establishing him as a first-rate film comedic and dramatic actor and a mentor to up-and-coming performers. “Robin’s Wish” avoids most of that, instead concentrating on the final years of his life after he settled in Marin County, California, with his third wife Susan Schneider, the movie’s central character and storyteller.

The stories of Williams’ suffering are illuminating and disturbing. David E. Kelley, who produced Williams’ final TV series “The Crazy Ones,” and Shawn Levy, who directed his performance as Teddy Roosevelt in the “A Night in the Museum” films detail bouts of desperation, sluggishness, and memorization problems. The production crew of both projects treated the actor’s issues discreetly, but it seems obvious that everyone in his orbit, including Schneider, is still traumatized by his death, and carries an unfounded but understandable load of guilt. Whenever anyone dies the way Williams died, loved ones’ first question is always, “Could I have done anything to prevent this?” Even when the answer is no, the question still gnaws.

Although “Robin’s Wish” is ultimately unwilling or unable to really grapple with the agony of those left behind after suicide, it is a compassionate film that will bring information about Williams’ condition to a wide audience. And it has many sections that are deeply moving, including those dealing with his performances for troops overseas, his commitment to a local playhouse’s open mic night, and his long friendship with actor Christopher Reeve, who was paralyzed in a riding accident. Williams completists will definitely want to see it.

Now available on digital platforms.