I know a couple named Jon and Jennifer Vickers, who moved to Three Oaks, Mich., (population 1,829) and bought the local movie theater. It’s 30 miles from the closest multiplex. They show first-run art films, and after eight years are a solid success. “The audience isn’t just the Chicago weekend people,” my friend Mary Jo Broderick tells me. She goes every week. “I see the same people I see in the supermarket in February.” The Vickers’ theater doesn’t show only “March of the Penguins” but Herzog, Wong Kar Wai, Bergman, Jarmusch. Every summer, they have a silent film festival.

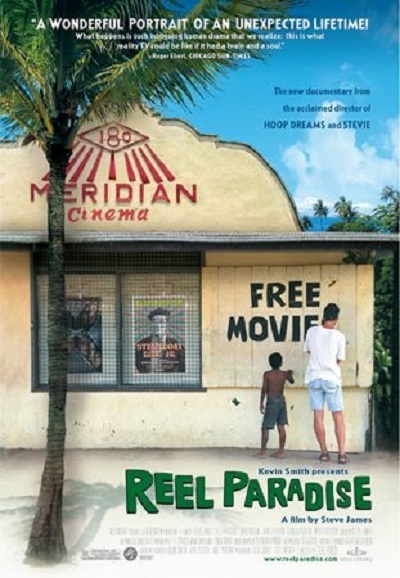

Steve James’ new documentary, “Reel Paradise,” is about a couple with similar idealism, who also move to a small town and buy the movie theater. Their theater is the 180 Meridian, on Taveuni, one of the Fiji Islands. They aren’t trying to bring art cinema to Fiji; they’re trying to bring the movies, period. The audience favorite is “Jackass,” a film so popular it is banned by the local authorities.

The man behind this idea is John Pierson, a producer’s rep well-known in indie film circles and crucial to the early success of such directors as Spike Lee (he invested in “She’s Gotta Have It”) and Michael Moore (“Roger & Me”). I’ve run into him over the years at festivals like Sundance. He tired of the indie-circuit routine and convinced his wife, Janet, and their children, Georgia, 16, and Wyatt, 13, to join him for a year running a movie theater in Fiji. They do not entirely share his enthusiasm.

James, who made “Hoop Dreams,” arrives in time to chronicle the final month of this experiment. What Pierson proved for sure is that if you show movies for free, you will get an audience. He also proved that a certain kind of great film, such as Buster Keaton’s “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” will draw a crowd. It’s always claimed that silent comedy is universal in its appeal; here’s your proof.

Pierson wanted to show all kinds of movies. He has a hit with “The Hot Chick.” He doesn’t do so well with more ambitious films. By the time James arrives with his camera, Pierson has contracted dengue fever and his son has taken over the day-to-day operations at the 180 Meridian. He may be the son of a legendary art film supporter, but Wyatt keeps his eye firmly on the box office: “If you show “Apocalypse Now” twice,” he tells his dad, “I guarantee no one will come the second night.” If a fortune is to be made by the Pierson family in the movie business, it may be made by Wyatt.

Fiji seems like a paradise from a distance, but when you live there it turns into a real place with real problems. There is the heat, the humidity, the lack of a power grid (the theater has its own generator). The projectionist tends to get drunk. There is the reality that Georgia is a teenager and interested in boys and, like all teenagers, wants to stay out past her curfew.

There are also two burglaries of the Piersons’ home. Suspicion for this crime falls upon people the Piersons like and trust. Considering that the island has only one road, it should not be hard to find the stolen computer, but it is. I am reminded of my visit to Bora Bora when “Hurricane” was being shot there. The movie publicist’s Jeep was stolen. The sheriff advised him to stand outside and wait until it came around; the island had one road, which circled the island.

The priests at the Catholic mission disapprove of many of Pierson’s movies (especially “Jackass”) and think that by showing them for free, he is undercutting the work ethic. The local teenagers hang out together and sometimes seem up to no good, but that is the nature of teenagers, and the dangers on Taveuni are mild compared to those in New York.

When the experiment ends and the Piersons return to America, the theater closes again. It is hard to say what they accomplished. It’s nice to think that if you show people movies, especially good movies, that will somehow change or improve their lives. But movies out of context are a curiosity and may play in unexpected ways. The politically correct might question a Three Stooges movie involving a South Seas cannibal’s boiling pot, but the audience explodes with such uncontrolled laughter that you can forget about hearing the dialogue.

The Piersons went, they showed movies, they returned. Taveuni is more or less the same. But by living and coping together for a year, the family is probably stronger and richer: Years from now, Georgia and Wyatt are going to be telling people about how their crazy parents opened a movie theater in Fiji, and in their voices you will hear that although they had their doubts at the time, they now think they were lucky to have such parents. Sometimes it’s not whether you succeed, but whether you try.