There are so many good things in “Random Hearts,” but they’re side by side instead of one after the other. They exist in the same film, but they don’t add up to the result of the film. Actually, the film has no result–just an ending, leaving us with all of those fine pieces, still waiting to come together. If this were a screenplay and not the final product, you could see how with one more rewrite, it might all fall into place.

The movie is about two somber, private adults who find out their spouses were having an affair with each other. They find out in an abrupt and final way, when the two cheaters are killed in the crash of a plane they weren’t supposed to be on.

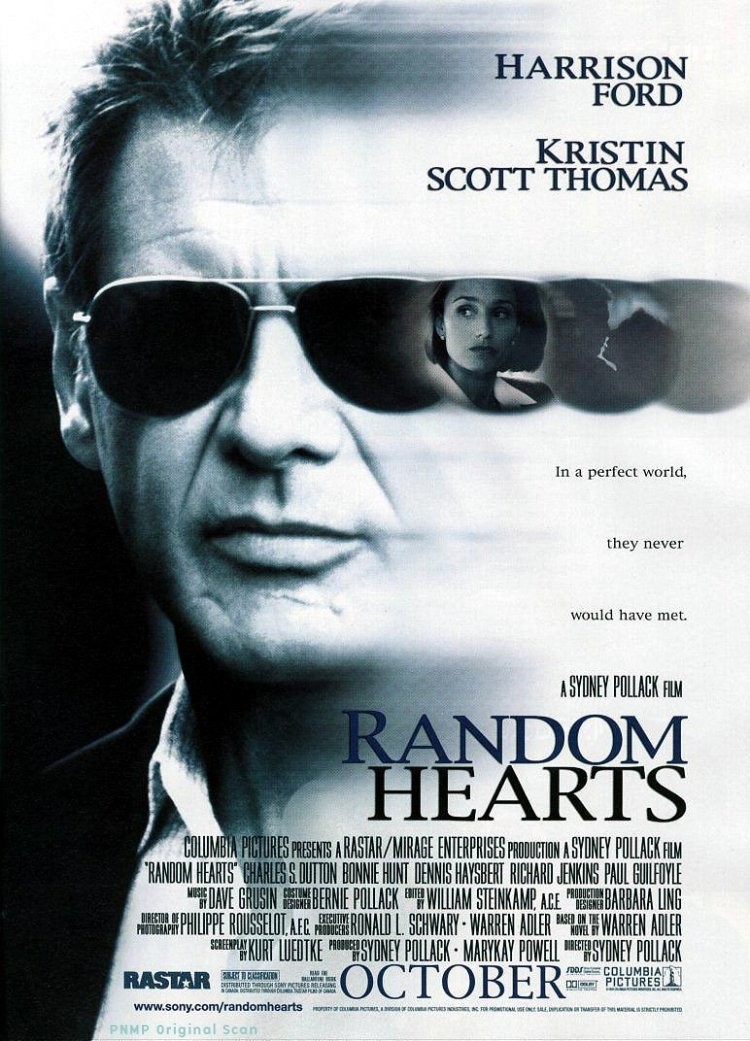

Curious, how neither of the survivors ever cries–or maybe they did when the movie wasn’t looking. If you think you’re happily married and your spouse dies and is exposed as a cheater, don’t you cry, anyway? Cry, because you loved them all the same, and now have lost not only your spouse but trust in your memories? “Random Hearts,” directed by Sydney Pollack, is too intent on its agenda to stop and observe that; it is about the living and not the dead. Harrison Ford plays a District of Columbia police sergeant, and Kristin Scott Thomas is a Republican congresswoman from New Hampshire. They meet about 45 minutes into the film, in a well-written scene in which he wants to find some kind of closure and she doesn’t. “What’s the last thing you remember about your husband that you know was true?” he asks her.

Although “Random Hearts” is primarily about the relationship between the two survivors, the early scenes have their own fascination. The movie makes it clear to us that the two cheaters are crash victims, but Ford and Thomas walk through a minefield of available information without making a connection. When Ford finally understands that his wife was not taking the flight for business reasons, he asks, “Are you saying she lied to me?” and we understand how hard this is for him to understand.

How does he feel? Angry? Betrayed? In denial? Ford is an actor able to keep his hand hidden, and he creates interest by not letting us know. He feels something strongly, and he wants answers. The congresswoman absorbs the new facts quickly and efficiently: They cheated, they’re dead, they’re in the past, it’s time to move on. Both of these acts are facades, broken by the survivors in a shocking moment when they fall upon each other in unseemly, and therefore convincing, passion.

There are subplots in the movie, but the emotional themes are more intriguing. One subplot involves Ford as an internal affairs investigator who is on the trail of a crooked cop who may have murdered a witness. All good stuff for another movie, but frankly it’s just a distraction here.

More interesting is her subplot, about the details of a congressional campaign, with Pollack convincing in a small role as an adviser who applies spin control to the story of the brave widow. We realize with a certain surprise that she is that rarity in a Hollywood movie, a good-hearted Republican, and later in the film, there’s amusing pillow talk. “Are you a Democrat?” she asks. “What if I am?” he says. “We talk,” she says, “and I give you books to read.” The real interest in the movie involves her emotional discoveries about herself. Ford seems stuck in the fact of betrayal. Thomas seems freed. She re-evaluates everything. Does she really want to run for office? What are her values? Startled to be plunged so quickly into a physical affair, she sees herself, the proper congresswoman, eagerly embracing physical abandon with this cop. “Nobody knows who I am anymore,” she says. “Nobody knows how easily I can do this.” You hear dialogue like that and you want more. You don’t want the resolution of the cop subplot, even if it is handled with a minimum of cheap violence. You like the fact that the movie doesn’t make one of these people good and the other bad, but makes both of them shell-shocked survivors with unexplored potential. You wish you could figure out what Harrison Ford is thinking, but then Ford has made a career out of hiding his thoughts.

Maybe the fundamental problem is the point of view. The interesting character here is the woman, but the movie’s star is Harrison Ford, and so the film is told from his point of view, and saddled with the unnecessary crime plot he drags in (a plot with no thematic connection to the rest of the story). How about a movie about a Republican congresswoman who loses her husband and gains a cop who looks just like Harrison Ford? All seen through her eyes. Now there would be a movie.