If you’ve read Patricia Highsmith’s novels about Tom Ripley, you know they can make your skin crawl. Ripley is a criminal of intelligence and cunning who gets away with murder. He’s charming and literate, and a monster.

It’s insidious, the way Highsmith seduces us into identifying with him and sharing his selfishness; Ripley believes that getting his own way is worth whatever price anyone else might have to pay. We all have a little of that in us.

The Talented Mr. Ripley was the first of the Ripley novels, published in the 1950s when Highsmith was already famous for writing Strangers on a Train, adapted by Hitchcock into one of his best films. In both stories,one man is strongly attracted to another one, and expresses his obsession through crime. Although it is never directly stated, there is obviously a buried level of homoerotic attraction; the criminal in both stories essentially wants to become the other man.

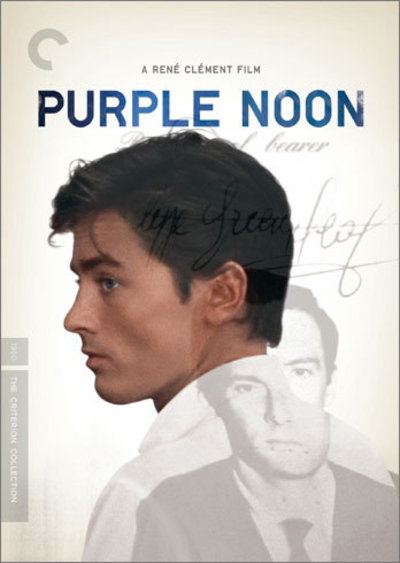

“Purple Noon” is Rene Clement‘s 1960 French adaptation of the first Ripley novel, starring a young Alain Delon as Tom Ripley, a man who is just learning that he can get away with almost anything. As the film opens, Tom has been sent to Rome to find his longtime friend Philippe (Maurice Ronet), a rich playboy whose parents want him to return to San Francisco. Tom is in no hurry to return to the States, and enjoys letting Philippe introduce him to the sweet life. (The movie’s opening scenes are on Rome’s Via Veneto, immortalized in Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita“; Nino Rota composed the music for both films.)

Philippe is dating Marge (Marie Laforet). Soon Tom Ripley wants to be dating Marge, too, and there is an odd little scene when he dresses in Philippe’s clothes and kisses the mirror in Philippe’s bedroom, whispering as if he were Philippe, “My Marge knows I love her and won’t go with that nasty Tom to San Francisco.” The three travel around Italy, and the men at one point strand Marge while they fly back to Rome for drinks and womanizing.

Eventually they all end up on a boat, sailing toward Sicily, and by now, it is fairly clear that Marge is superfluous, and that the two men, unable to acknowledge their sexual attraction, are expressing it through hostility. Tom overhears Philippe’s plans for putting him ashore. Philippe mistreats Tom, to see how much he’ll put up with. Tom moves on Marge. Philippe banishes Tom to a rowboat, and while Marge and Philippe make love, the tow rope splits, and Tom is marooned alone in the ocean, the sun blistering his skin. Tom is rescued. Margeis put ashore.

And then — read no further if you’d rather not know — there is a scuffle and Tom kills Philippe and disposes of his body — safely, so he thinks.

All of these events are essentially just the set-up for the real story, which is about how Tom, improvising brilliantly, plans to get away with the murder and win not only Philippe’s fortune but even Marge. Rene Clement’s film is shot in sunny pastels and a travelog style that works as an eerie contrast to Tom’s scheme. The Nino Rota music doesn’t often go for sinister undertones; instead, it’s quietly, unobtrusively cheerful, which is all the creepier (Clement uses less music, less obviously, than Fellini). The young Alain Delon, who in 1960 had not yet matured into his full status as a matinee idol, seems young and callow, which is right for the role; “Purple Noon” is essentially about an aimless young man who has stumbled onto his life’s work.

The fascination in Highsmith’s Ripley novels resides in the way Ripley gets away with his crimes. In most of them, his advance planning is meticulous; only in this first adventure does he have crime thrust upon him.

Ripley in the later novels has become a committed hedonist, devoted to great comfort, understated taste and civilized interests. He has wonderful relationships with women, who never fully understand who or what he is. He has friendships — real ones — with many of his victims. His crimes are like moves in a chess game; he understands that as much as he may like and respect his opponents, he must end with a checkmate.

The best thing about the film is the way the plot devises a way for Ripley to create a perfect cover-up, a substitution of bodies (for which a second corpse comes in handy). Ripley’s meticulous timing, quick thinking and brilliant invention snatch victory out of the hands of danger.

When he made it, Rene Clement may have been inspired by Clouzot’s “Diabolique” (1955), another famous story of devious plotting and double-crossing. The films have certain similarities. “Diabolique’s” two women have unexpressed lesbian feelings, just as “Purple Noon’s” men suppress their homosexuality. Both stories involve drowned corpses that do, or do not, appear or disappear on demand. And both have less than satisfactory endings.

“Diabolique” can end as it does only because the police inspector doesn’t act on all of the knowledge he has. And “Purple Noon” ends as it does only because Clement doesn’t have Highsmith’s iron nerve. Do you want to know if Ripley finally gets caught? All I will tell you is that there were more Ripley novels than you would expect on the basis of this movie’s ending.