When did the laughs go out of stand-up comedy? When did stand-up comedians stop being humorists and start being “personalities,” whose career moves follow a carefully defined trajectory from local clubs to big clubs to the “Tonight Show” to cable to network to movie stardom? When did stand-ups start being bores? I ask these questions having recently listened to an excruciatingly boring radio phone-in program with Richard Lewis as the guest host and Garry Shandling as his guest. Jokes were not told on this program, which consisted mostly of Lewis flattering Shandling for being such a great guy and being so terrific to come on the show. When callers phoned in, Lewis immediately started badgering them – “What’s your question for Garry Shandling?” – and then cut them off, even though most of the callers sounded smarter, funnier and certainly less hysterical than he did. As for Shandling, he was not very funny, but then he doesn’t need to be now that he has made it as an elder statesman with his own show. He functioned basically as an object of envy for those who wish it were their show and not Garry Shandling’s.

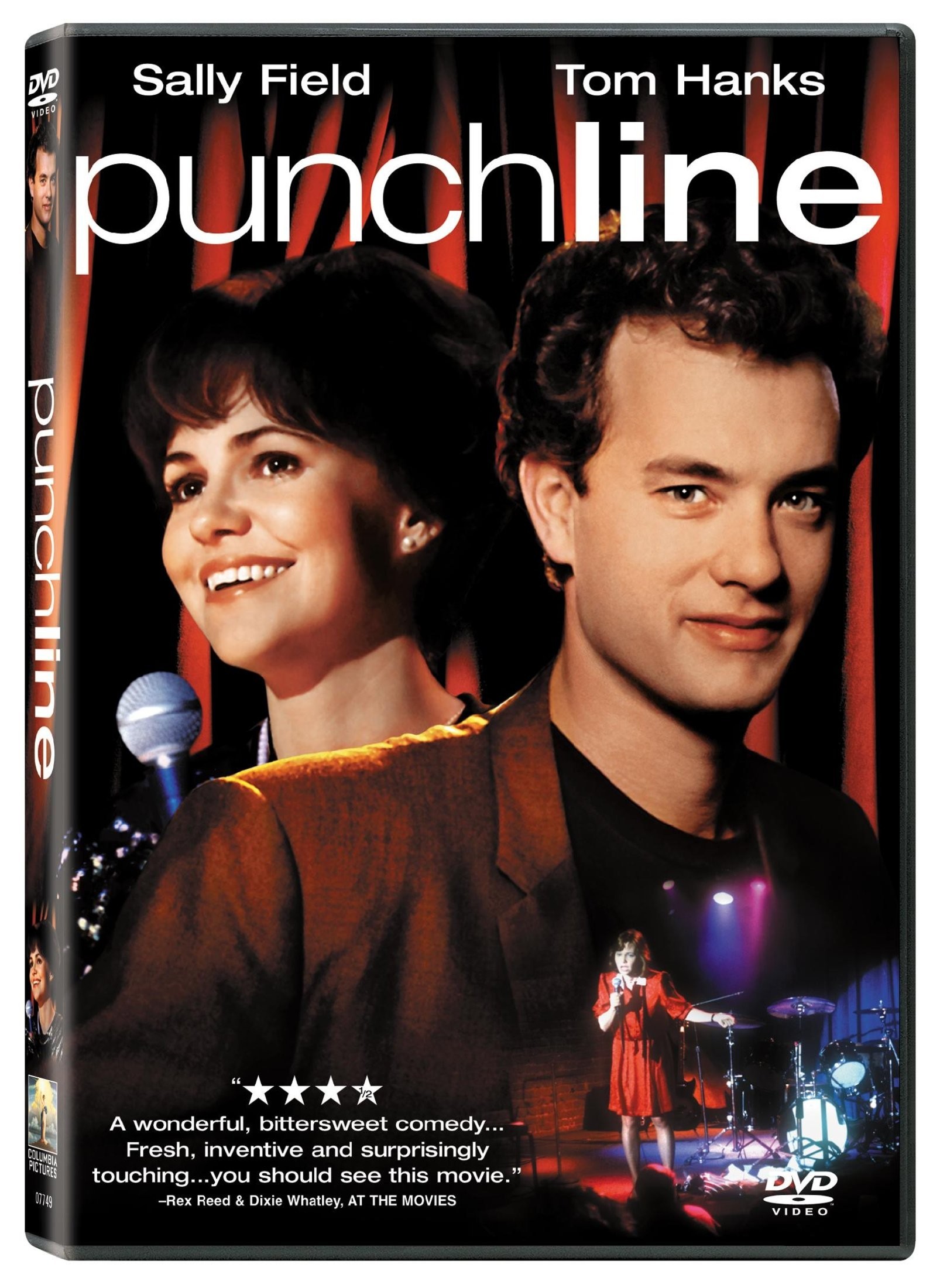

Everybody knows that stand-up comics represent the unhappiest and most screwed up people in show business, and it is not by accident that their routines are filled with hostility toward the audience (“This’ll kill ya”) and masochistic self-pity (“I’m dying up here!”). Occasionally a comedian is able to make this funny, as Rodney Dangerfield and Jay Leno and, yes, Shandling, do in their contrasting ways, but usually it is simply sick, a public display of ego and ambition unmatched by talent or imagination. If these guys want to perform so badly, why didn’t they take accordion lessons? This outburst is occasioned by “Punchline,” a pathetic movie into which a great deal of energy and talent has disappeared. The movie stars Sally Field as a housewife and mother who dreams of becoming a stand-up comedian and Tom Hanks as a failed medical student who also wants to be a comic and has had more experience than Field. They meet at a middle-level comedy club, where Field flops, Hanks succeeds, they become friends and he tries to teach her the ropes, while meanwhile her marriage is falling apart and her husband is threatening to take the kids and leave.

If this situation had been treated as slapstick, it might have worked. If it had been treated seriously, it also might have worked.

But instead of taking the characters seriously, the movie makes the fatal mistake of taking stand-up seriously. And if you’re gonna do that, you’d better have good material.

It is a fact, sad but true, that none of the stand-up routines by Field in this movie are any good – not the ones that are supposed to be bad and not the ones that are supposed to be good, either. And Hanks barely does better. The movie does not seem to know it is about two would-be comics who are both lacking in talent.

The structure of the film will be familiar to Field fans. It shows her with lots of heart and pluck as she does what she knows is right.

At the end, of course, she gets it both ways: She succeeds, while her husband and children cheer her on and learn to accept Mom’s new obsession. But to get from the beginning to the end requires an awkward, unbelievable and thankless about-face by her husband (John Goodman), who appears first as a monster and then as a nice guy. No attempt is made to explain this personality shift; it’s simply dictated by the plot.

The best performance in the movie is by Mark Rydell, a movie director who moonlights as Romeo, the owner of the club where much of the action takes place. His character has the rhythms, the values, the presence and the delivery to convince us he knows something about show business and stand-up comedy. Most of the other characters are babes in the woods.

The problem may be that the movie isn’t nearly tough enough. It needs to be more hard-boiled, more merciless in its dissection of egos, more perceptive about the cutthroat nature of show business. Stand-up comedy is the nation’s newest spectator sport, and any city worth its salt now has one or more comedy clubs in which one “comic” after another is thrown to the wolves. What’s really going on here? Is it really just a case of amateurs dreaming of getting into show biz? Or is it something deeper and sicker? Comics used to be part of the act in show business – along with singers, dancers, tumblers and magicians and anybody else Ed Sullivan could dredge up. But why a whole evening of nothing but comedy? Nobody wants to laugh that much. What’s really going on is that the audience is judging the gall and self-confidence of would-be comics, who often fail and perhaps enjoy failing. It is some kind of masochistic rite that has little to do with humor, which is why when a comic makes it big he immediately turns into a humanitarian statesman and starts volunteering for charity telethons. If you’re born feeling guilty, and the audience has stopped giving you the rejection you know you so richly deserve, then you’ve got to find another way to feed your conscience. “Punchline” doesn’t seem to know this, or much else about stand-up comedy.