If you’re a Pulp fan, you know that cutting lead singer Jarvis Cocker off just as he starts to pick up speed is tantamount to blasphemy. But that’s exactly what director Florian Habicht does at the start of concert doc “Pulp: a Film About Life, Death, and Supermarkets.” Later, Habicht reveals that he’s only doing what Cocker already did during the band’s final concert in 2012. During that live show, Cocker pauses to introduce his band before he leads them in finishing off “Common People,” Pulp’s most famous single.

Therein lies Habicht’s biggest misstep: he lets Cocker call the shots, and subordinates Cocker’s band, a funny hybrid of cheeky Elvis Costello-style bawdiness, and Smiths-like naive social realism, to his ego. Even the blue-collar residents of Sheffield are patronizingly presented as exemplars of Cocker’s artistic genius. They talk endlessly about Pulp, a band whose members all hail from Sheffield. But Habicht’s film never goes beyond idol worship since his film only succeeds at reproducing Cocker’s myopic vision of his band.

But instead of focusing on the band’s last concert, Habicht alternatively mythologizes Cocker, and his hometown’s residents. This is because, as Pulp biographer Owen Hatherley explains, “Common People” reveals Pulp’s class-conscious concerns. So, we see the residents of Sheffield as a collection of quaint salt-of-the-earth types, like the little old ladies that talk about dancing, and the middle-aged, all-female a capella group that covers “Common People.” What we don’t see is Sheffield residents explaining what lyrics like “I want to sleep with common people like you” mean to them, the common people of Cocker’s imagination.

To be fair, some of Habicht’s interviews are charmingly off-the-cuff. This is especially true of the handful of scenes featuring Bomar, a mascara-clad lad who titters about Habicht’s approach from behind an expertly poised cigarette (“Hopes and dreams of the common man, eh?”). And there are breathtaking images of Sheffield at sunrise that make the city look like a breathtaking Anytown, UK. These city views are beautiful because they show you a landscape of the mind’s eye, the kind you might romanticize all out of proportion if your daily commute took you through Sheffield.

But those beautiful, singular images mean nothing without human residents worth caring about. Even the tourists who come to town just for Pulp, like American fan Melina, are strictly defined by their love of Pulp. But Melina’s Cocker worship makes no sense since Habicht simply doesn’t show enough concert footage. Seeing Pulp play might make viewers understand why a diehard like Cherie is so proud to own underwear that “says ‘Pulp’ on the front, and ‘Jarvis’ on my bum.” That footage might also answer Pulp guitarist Richard Hawley when he jokingly questions how Pulp survived the 13 years that separate “It,” Pulp’s first album, from “Different Class,” their first and only platinum album.

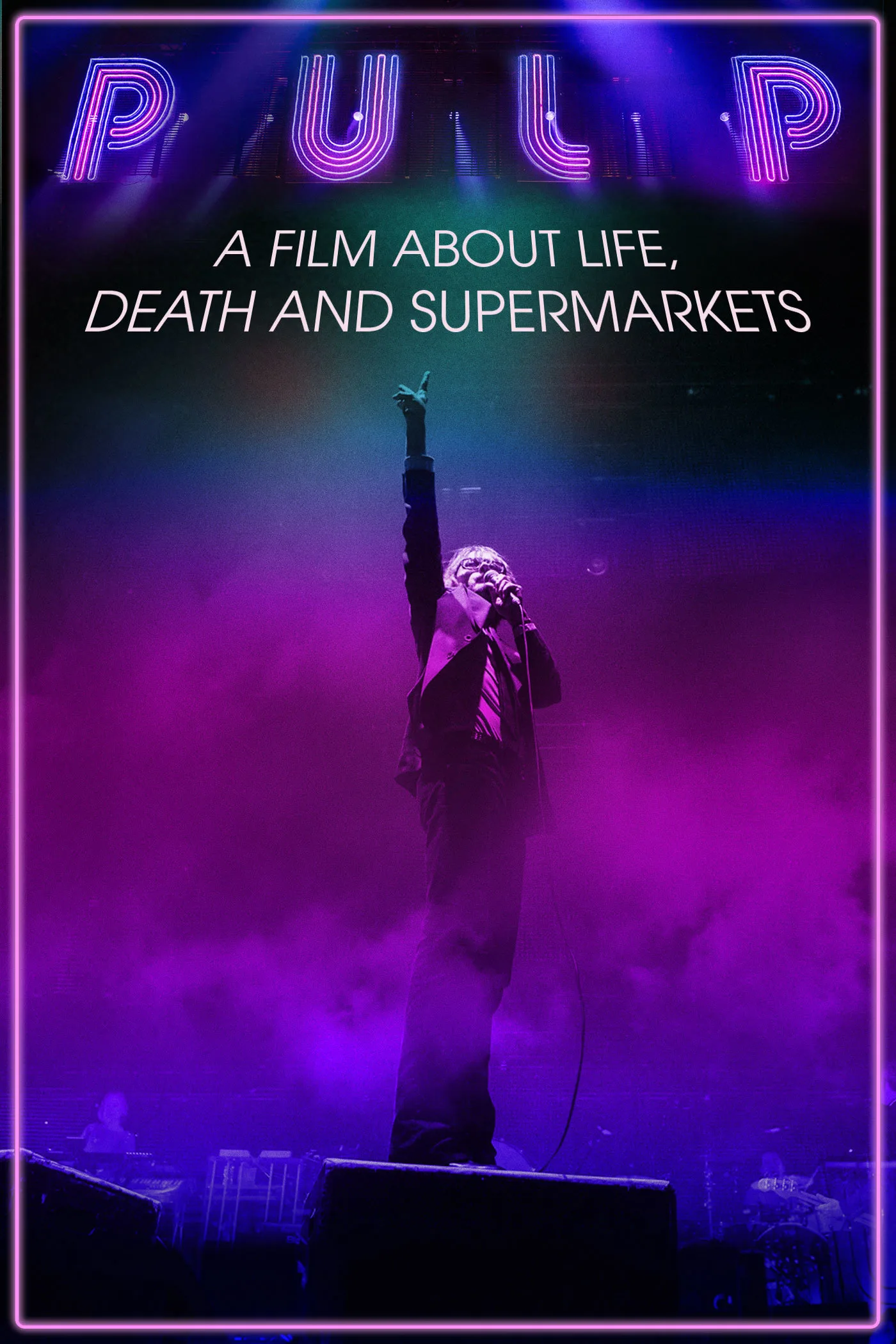

Habicht does eventually show us Cocker performing, but only for the sake of indulging his character arc. Stardom, as Cocker mutters, left him feeling like an abductee torture victim, and that sentiment is pointedly expressed in “This is Hardcore,” Pulp’s first post-“Different Class” record. When Cocker sings that album’s title song, it’s well after we’ve seen everyone from Melina to the group’s tour manager wonder how Cocker could be so sexy. If you can overlook how over-edited this scene is, you might see why Cocker is so beloved just by observing his on-stage body language: hands on hips, heels off the ground, and fingers eagerly snaking down his front. Cocker’s burlesque is only semi-serious, as you see when he lies on his back, and pumps his legs languidly. But he’s a damn fine performer in spite of, and not because of his routine’s schticky veneer. Unfortunately, he’s presented as the only noteworthy performer on-stage.

Cocker’s magnetic persona is a huge part of Pulp’s identity, but it’s not the band’s greatest legacy. So don’t be surprised when Cocker’s gas-leak hiss of a voice is drowned out by smoke machine cannons, and fails to swell until it bursts at the end of “Common People.” The song never takes off since its lead performer is more interested in taking a bow than in earning one.