Peter Greenaway’s “Prospero’s Books” is not a movie in the sense that we usually employ the word. It’s an experiment in form and content. It is likely to bore most audiences, but will enchant others — especially those able to free themselves from the notion that movies must tell stories. This film should be approached like a record album or an art book. Each “page” is there to be studied in its complexity and richness, while on the soundtrack we hear one of the great voices in theater history, John Gielgud’s.

Greenaway begins with a crucial piece of information from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, that final and most symmetrically perfect of the playwright’s works. Prospero, once duke of Milan, has been tossed by a storm onto a lost island, along with his daughter, Miranda, various crew members and such resident sprites and monsters as Ariel and Caliban. But he has managed to save his books from the tempest – books he prizes more than his dukedom – and Greenaway wonders about that water-soaked library. What books did he have, and how did he use them?

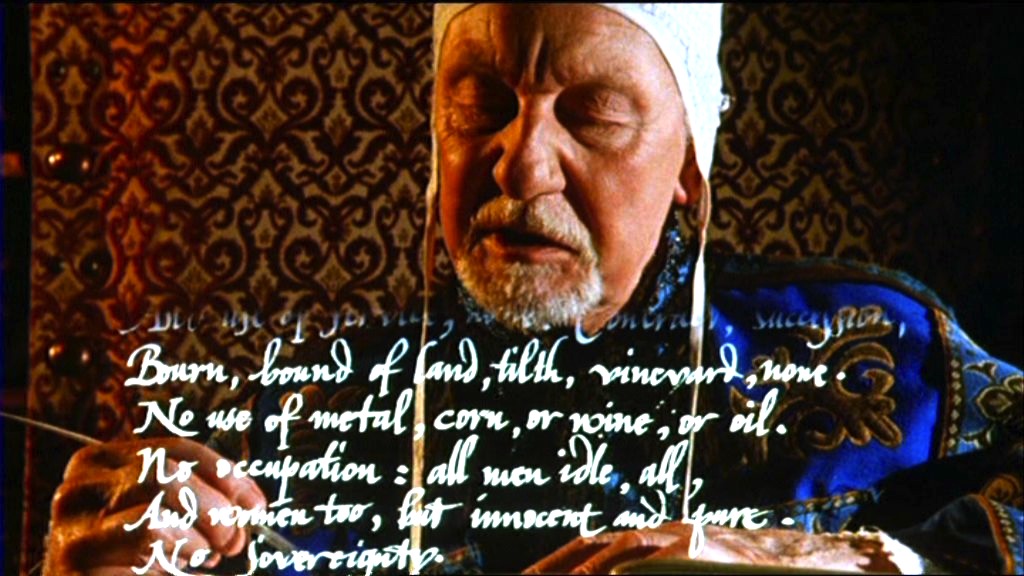

The books, their typography, calligraphy and illustrations, are photographed in voluptuous detail. As Gielgud takes center screen in a narrative adapted from Shakespeare, Greenaway overlays those basic images of Prospero with a series of transparencies. Pages of books appear over the central image or slide in from the sides, sometimes two or three deep, pausing for our consideration, and then vanishing to be replaced by still other images and words. The effect is something like those high school biology texts in which succeeding sheets of transparent plastic revealed the depths of the human body, one layer after another.

The human images in the film center around the idea of nudity. Here, as in such earlier films as “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover,” the form and fleshiness of the nude is Greenaway’s visual obsession. There are, at various times, dozens or even hundreds of unclothed bodies on the screen, seen by the director in terms of Renaissance painting, and by the philistines at the Motion Picture Association of America as, needless to say, cause for an R rating. Gielgud presides over all of these images — printed and fleshy — as a sorcerer who alone understands their master purpose.

This is not the film to see if you want to witness a performance of The Tempest. It is,however, a fascinating film if you are interested in the play, in Shakespeare or in the breathtaking era when manuscripts and the printed word began to pull Europe out of the Dark Ages and into what we congratulate ourselves is a more enlightened time. “Prospero’s Books” would be an ideal film to watch on laserdisc, where with a hand-held remote you could freeze any frame and study its subtleties. It is also a wonderful film to listen to; Gielgud does a great many of the speaking roles, and, at 86, seems in full and sonorous command of his vocal instrument.

“Prospero’s Books” really exists outside criticism. All I can do is describe it. Most of the reviews of this film have missed the point; this is not a narrative, it need not make sense, and it is not “too difficult” because it could not have been any less so. It is simply a work of original art, which Greenaway asks us to accept or reject on his own terms.