“I’m a plain workingman. You don’t know what it means to a guy like me to take a dip in a private pool.” Duke (Cory Allen), the self-regarding beatnik-drifter hero of “Private Property,” tells that to Ann Carlyle (Kate Manx), a rich, unhappy housewife that he wants to seduce. Oh, yeah, Duke wants her, all right—even though he claims he’s only hanging around Ann’s home in the hills above Los Angeles when her husband’s away so that he can lure her to the house next door, where he and his pal Boots (Warren Oates) are holed up, and let Boots rape her.

Apparently Duke got to have “the last one”—the movie is vague about what, exactly, this means—and insists he’s not emotionally invested, just being equitable and doing his buddy a solid. But you can tell by the way Duke obsesses over Ann and the way his voice cracks when he insistently sweet-talks her that he’s smitten. Whatever she represents to him—a means to avenge himself against the elites who’ve kept him from succeeding, maybe; like a chance to key an imported sports car or spray graffiti on a CEO’s portrait—his desire for human connection gums up his world view, and makes it tough for him to be the coldblooded sociopath he claims he is.

And you can tell by the way Ann lets herself be drawn to Duke that she’s lonely enough to fail to see through his manipulations—or that she knows on some level how sick he is but has suppressed her self-preservation instinct because her husband, Roger (Robert Ward), has no real passion for her. She’s his trophy, and the spacious, airy home with its cliff-side pool is the glass case that Roger keeps her in. Sooner or later, one of these characters is going to break the glass. Will it be Duke, or Boots? Or Ann?

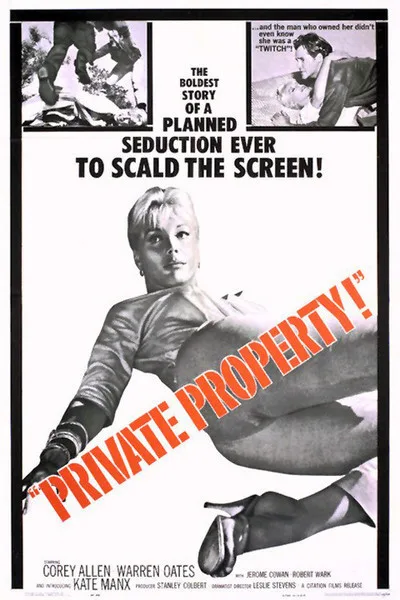

“Private Property” was written and directed by Leslie Stevens, whose best known credits are probably the script to “The Left-Handed Gun,” various episodes of “The Outer Limits” and the sorts of live theater broadcasts that flourished in the 1950s. Long thought lost, and restored for 2016 theatrical release by Cinelicious, it’s an imperfect but fascinating work, and one of the great “yes, but have you seen” films of the mid-20th century—you know, the sort of title that a buff will bring up in a conversation about certain genres, feeling sure that the other person hasn’t heard of it.

The characterizations and performances are ultimately not as rewarding as one might hope, given how compelling the story is from its first frame. The motivations are too obviously informed by the pop-Freud and watered-down Marx that many 20th century American writers mistook for depth and cultural context. Oates, almost ten years away from his rise to cult stardom and easily the best actor of the bunch, is a supporting player and spends much of the film seething silently while Allen, who’s touching and scary but distractingly self conscious, and Manx, who’s all sweetness and desperation and not enough suppressed hunger, occupy the film’s foreground. And although “Private Property” does a magnificent job of building tension throughout its first hour, its end game is disappointingly conventional, complete with music that tries to convince us that a domestic horror show is a happy ending. (In fairness, the same could be said for subsequent thrillers in the same vein, such as “Fatal Attraction,” “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle,” “Unlawful Entry” and “Pacific Heights.”)

That said, “Private Property” is a terrific example of the spell that a confident film can weave by placing a handful of troubled characters in a confined location, and in the end it does feel like as much of a tragedy as a potboiler. Even when Allen oversells or fumbles moments that a handsome-neurotic star of that same era (like Paul Newman) could’ve transformed into antihero black magic, the character still holds the screen, because there’s enough of the aggrieved child in Duke that you feel for him even when he’s being scary and disgusting. And Stevens and his cinematographer Ted McCord (“The Sound of Music”) come up with images that are metaphorically richer than Stevens’ very best dialogue, such as a wide shot of Duke and Ann drunkenly slow-dancing into the deep background of a shot, their spiraling movements framed through a booze-smeared tumbler in the foreground.

Class resentment fuels a lot of the action. Duke’s monologues intellectualize the contempt that other working class men express openly for the rich wimps they believe are lording it over them with their fancy cars, big homes and fat bankrolls, and most of all, the beautiful young women they think they’d have a shot with if the financial playing field were level. (If Duke and Boots could know that guys like Roger barely give guys like them a second thought, they’d be even madder.) The movie offers evidence supporting the idea that to Roger, Ann is a possession like everything else he owns, although his kind but clueless smile in scenes where he brushes off her advances confirms that he would never describe their relationship that way. A dinner-table conversation between Ann and Robert, who seems to be about twenty years older than his wife, reveals that Ann was 19 when he met her. She wants kids. Roger is content to keep things status quo. When he shows her a blueprint of a boat he wants to build and casually mentions that it can house four people, Ann’s face lights up as she repeats “Four?”, then falls as he amends it to two.

But the film doesn’t romanticize Duke’s craving for Ann or make it seem as if he could somehow “rescue” her. It shows that the sexist entitlement embodied by Roger is baked into the marrow of Duke and Boots, too, but because they lack Roger’s breeding, they have no idea that they sound like boors or thugs when they talk about Ann, or about women generally. When they spy on Ann sunbathing and swimming from a couch placed in a second floor window next door, their casually objectifying dialogue and the framing of Ann in the distance and the men’s looming heads’ in the foreground makes it seem as if they’re just a couple of ordinary guys talking about a sexy lady on TV. The specific language that Duke uses when he talks about Ann makes it hard to tell where class resentment leaves off and hatred of women starts. He says he really wants to “get into” Roger’s white Corvette, and in an especially chilling scene, tells Boots, “She’s got cow eyes, and she gives butter, and if I’d wanted to, I could’ve had her in the garage or on the patio or pushed her in the pool.”

The film deserves to be more widely seen for its ability to disturb artfully, without crude shocks, and for its sincere fascination with its characters’ tortured psyches. You hear this said often about older films, but in this case it’s true: for all its 1960-ness, it feels contemporary; it could certainly be remade without changing much. Although it contains no onscreen sex, artfully obscures its nastier violence with editing, and confines its profanity to a handful of fairly mild words, it’s a disturbing film, not just because of the drifters’ ugly plot, but because of the detailed portrait of American desperation, delusion and loneliness that it paints. It could be shown on a double bill with a far more brutal film released that year, “Psycho,” which is likewise concerned with the shame- and greed-ridden underbelly of Eisenhower-era American life.