Shane Carruth‘s “Primer” opens with four techheads addressing envelopes to possible investors; they seek venture capital for a machine they’re building in the garage. They’re not entirely sure what the machine does, although it certainly does something. Their dialogue is halfway between shop talk and one of those articles in Wired magazine that you never finish. We don’t understand most of what they’re saying, and neither, perhaps, do they, but we get the drift. Challenging us to listen closely, to half-understand what they half-understand, is one of the ways the film sucks us in.

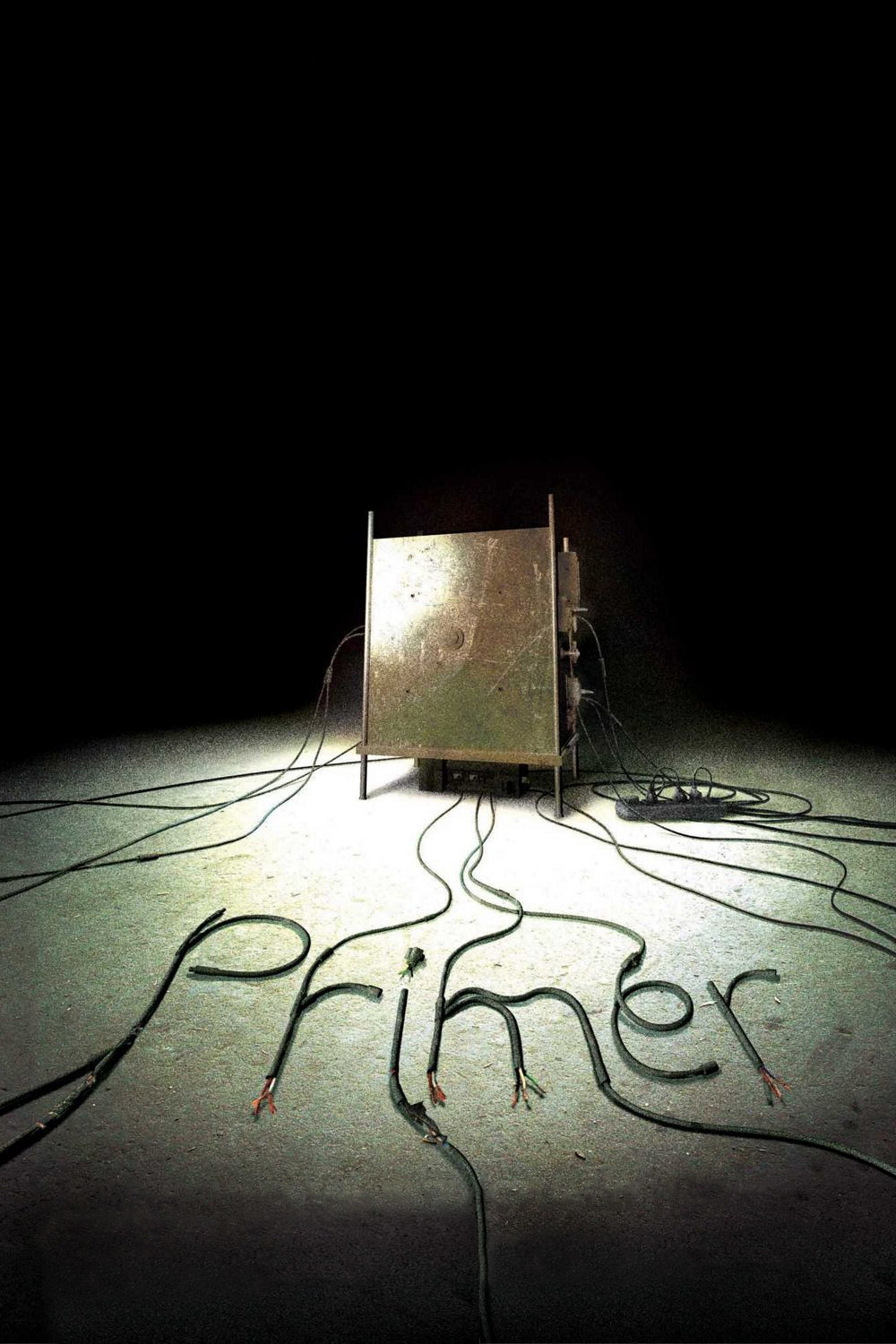

They steal a catalytic converter for its platinum, and plunder a refrigerator for its freon. Their budget is so small, they could cash the checks on the bus. Aaron and Abe, agreeing that whatever they’ve invented, they’re the ones who invented it, subtly eliminate the other two from the enterprise. They then regard something that looks like an insulated shipping container with wires and dials and coils stuff. This is odd: It secretes protein. More protein than it has time to secrete. Measuring the protein’s rate of growth, they determine that one minute in the garage is equal to 1,347 minutes in the machine.

Is time in the machine different than time outside the machine? Apparently. But that would make it some kind of time machine, wouldn’t it? Hard to believe. Aaron (Shane Carruth) and Abe (David Sullivan) ponder the machine and look at their results and Aaron concludes it is “the most important thing any living being has ever witnessed.” But what is it?

There’s a fascination in the way they talk with each other, quickly, softly, excitedly. It’s better, actually, that we don’t understand everything they say, because that makes us feel more like eavesdroppers and less like the passive audience for predigested dialogue. We can see where they’re heading, especially after … well, I don’t want to give away some of the plot, and I may not understand the rest, but it would appear that they can travel through time. They learn this by seeing their doubles before they have even tried time travel — proof that later they will travel back to now. Meanwhile (is that the word?) a larger model of the machine is/was assembled in a storage locker by them/their doubles.

Should they personally experiment with time travel? Yes, manifestly, because they already have. “I can think of no way in which this thing would be considered even remotely close to safe,” one of them says. But they try it out, journeying into the recent past and buying some mutual funds they know will rise in value.

It seems to work. The side effect, however, is that occasionally there are two of them: the Abe or Aaron who originally lived through the time, and the one who has gone back to the time and is living through it simultaneously. One is a double. Which one? There is a shot where they watch “themselves” from a distance, and we assume those they’re watching are themselves living in ordinary time, and they are themselves having traveled back to observe them. But which Abe or Aaron is the real one? If they met, how would they speak? If two sets of the same atoms exist in the same universe at the same time, where did the additional atoms come from? It can make you hungry, thinking about questions like that. “I haven’t eaten since later this afternoon,” one complains.

“Primer” is a puzzle film that will leave you wondering about paradoxes, loopholes, loose ends, events without explanation, chronologies that don’t seem to fit. Abe and Aaron wonder, too, and what seems at first like a perfectly straightforward method for using the machine turns out to be alarmingly complicated; various generations of themselves and their actions prove impossible to keep straight. Carruth handles the problems in an admirably understated way; when one of the characters begins to bleed a little from an ear, what does that mean? Will he be injured in a past he has not yet visited? In that case, is he the double? What happened to the being who arrived at this moment the old-fashioned way, before having traveled back?

The movie delights me with its cocky confidence that the audience can keep up. “Primer” is a film for nerds, geeks, brainiacs, Academic Decathlon winners, programmers, philosophers and the kinds of people who have made it this far into the review. It will surely be hated by those who “go to the movies to be entertained,” and embraced and debated by others, who will find it entertains the parts the others do not reach. It is maddening, fascinating and completely successful

Note: Carruth wrote, directed and edited the movie, composed the score, and starred in it. The budget was reportedly around $7,000, but that was enough: The movie never looks cheap, because every shot looks as it must look. In a New York Times interview, Carruth said he filmed largely in his own garage, and at times he was no more sure what he was creating than his characters were. “Primer” won the award for best drama at Sundance 2004.