“‘Priest,’ ” one critic has written, “vigorously attack(s) the views of the Roman Catholic Church on homosexuality,” which is just the way the filmmakers probably want the film to be positioned. Actually the film is an attack on the vow of celibacy, preferring sexuality of any sort to the notion that men should, could or would live chastely.

The story takes us into a Liverpool rectory where the senior priest sleeps with the pretty black housekeeper, and the younger priest removes his Roman collar for nighttime soirees in gay bars.

When he and his partner are caught in a police sweep, he is disgraced, but the older priest is pleased that the young man has finally gotten in touch with his emotions, and begs him to return to the church to celebrate mass with him. (The bishop, who advises the offender to “p- – – off out of my diocese,” is portrayed, like all the church authorities, as a dried-up old bean.) The question of whether priests should be celibate is the subject of much debate right now. What is not in doubt is that, to be ordained, they have to promise to be celibate. Nobody has forced them to become priests, and rules are rules. The filmmakers seem to feel that since they wouldn’t want to live that way, of course it is wicked that priests must.

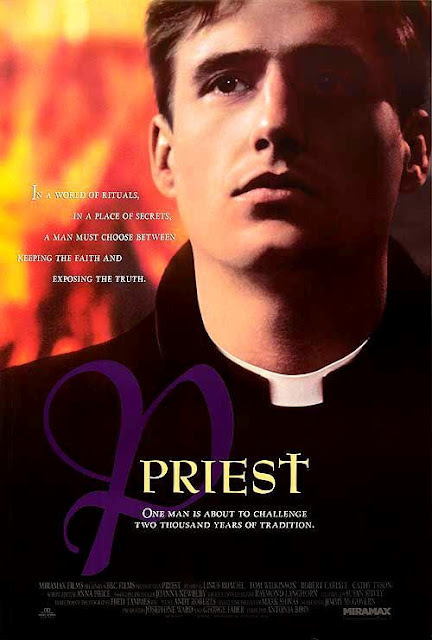

I am aware that the touchy-feely movement is so well established that no commercial film could seriously argue for celibacy. What I object to is the use of the church as a spice for an otherwise lame story; take away the occupations of the two central characters, and the rest of the film’s events would be laid bare as tiresome sexual politics. The most obnoxious scene in the film is the one where the young priest, tortured by the needs of the flesh and by another problem we will soon get to, lectures Christ on the cross: “If you were here, you’d . . .” Well, what? Advise him to go out and get laid? The priest, named Father Greg and played by Linus Roache, picks up Graham (Robert Carlyle) for a night of what he hopes will be anonymous sex, but later Graham recognizes him on the street, and soon they are in love. This is all done by fiat; the two men are not allowed to get to know one another, or to have conversations of any meaning, since the movie is not really about their relationship, but about how backward the church is in opposing it.

Instead of taking the time to explore the sexuality of the two priests in a thoughtful way, “Priest” crams in another plot, this one based on that old chestnut, the inviolable secrecy of the confessional. Father Greg learns while hearing a confession that a young girl is being sexually abused by her father. What to do? Of course (as the filmmakers no doubt learned from Alfred Hitchcock’s “I Confess”) he cannot break the seal of the confessional – a rule that, for the convenience of the plot, he takes much more seriously than the rules about sex. This dilemma also figures in his anguished monologue to Jesus.

Once again, the church is used as spice. (Can you imagine audiences getting worked up over the confidential nature of a lawyer-client or a doctor-patient relationship?) But here the movie leaves a hole wide enough to run a cathedral through. The girl’s father confronts the priest in the confessional, threatens him, and tells the priest he plans to keep right on with his evil practice (we don’t simply have a child abuser here, but a spokesman for incest).

What the film fails to realize is that this conversation is not protected by the sacramental seal because the sinner makes it absolutely clear he is not asking forgiveness, does not repent and plans to keep right on sinning as long as he can get away with it. At this point, Father Greg should pick up the phone and call the cops.

The unexamined assumptions in the “Priest” screenplay are shallow and exploitative. The movie argues that the hidebound and outdated rules of the church are responsible for some people (priests) not having sex although they should, while others (incestuous parents) can keep on having it although they shouldn’t.

For this movie to be described as a moral statement about anything other than the filmmaker’s prejudices is beyond belief.