“Point of No Return” is a “Pygmalion” for our angry age. In both stories, an older teacher picks a girl out of the gutter and teaches her new skills. Professor Higgins taught Eliza to act like a lady, and now Bob teaches Maggie to be a lady and a cold-blooded assassin.

Both women get a lot of lessons on how to hold their forks.

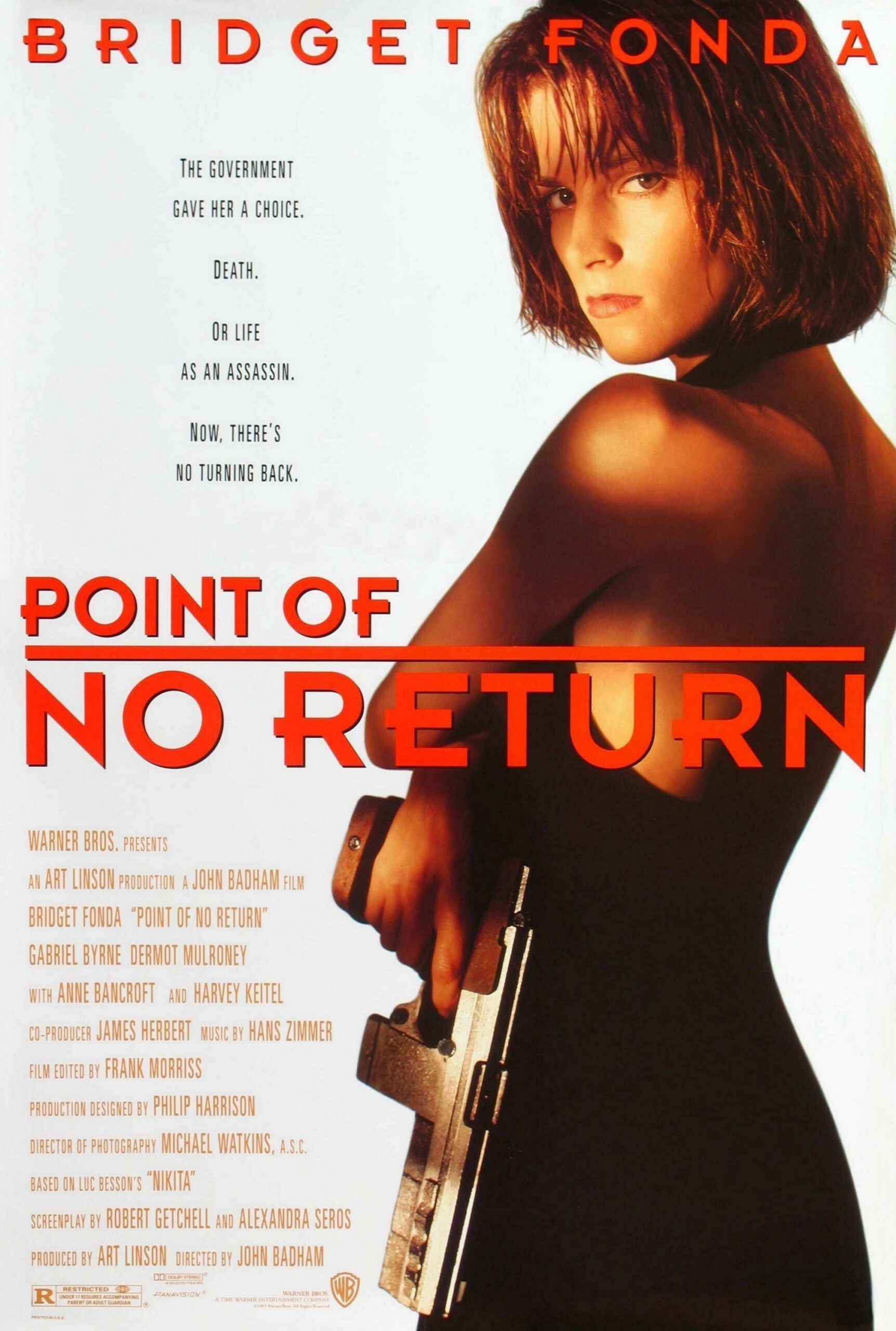

The movie stars Bridget Fonda as Maggie, a girl of the streets, who is high on drugs when she kills a cop during a drugstore robbery that goes wrong. She is sentenced to death, and to keep the story rolling along, the movie shows the sentence being carried out almost immediately (not likely in California).

But, in fact, she is not killed; the execution is a cover, and she awakens inside a secret government school for killers, where Bob (Gabriel Byrne) tells her she has two choices: Go along with the program, or end up underneath the tombstone that already carries her name. Maggie is put through a quick course in weapons, explosives, martial arts and good manners. The last is taught by Anne Bancroft, as an older woman who gives her a beauty makeover. She comes to the center looking like a wolf girl; she leaves as a well-groomed beauty.

Bob gives her a new identity and sends her to live in Venice, Calif., where she soon falls in love with the photographer who lives downstairs (Dermot Mulroney). But soon she is assigned to murder a man in a restaurant, and eventually it becomes clear that Bob’s bosses consider her expendable. Bob, of course, has fallen quietly in love with her, a feeling that business keeps him from acting on.

If this story sounds familiar, you have seen “La Femme Nikita,” a 1991 French thriller by Luc Besson, which was bought by Warner Bros. to be remade into this American version by John Badham (“WarGames,” “Stakeout“). The notion of pouring European films into Hollywood molds didn’t work out recently with “The Vanishing” (1993), but “Point of No Return” is actually a fairly effective and faithful adaptation, and Bridget Fonda manages the wild identity-swings of her role with intensity and conviction, although not the same almost poetic sadness that Anne Parillaud brought to the original movie.

If I didn’t feel the same degree of involvement with “Point of No Return” that I did with “La Femme Nikita,” it may be because the two movies are so similar in plot, look and feel. I had deja vu all through the movie. There are a few changes, mostly not for the better. By making the heroine’s boyfriend a photographer this time, instead of a check-out clerk, the movie loses the poignancy of their relationship; Nikita liked her clerk precisely because he was completely lacking in aggression.

The movie does, at least, end on the correct note of suitably bleak melancholia. Hollywood sometimes feels it necessary to squeeze all films into happy endings (in the case of a violent thriller, that means the right people get killed). That would be all wrong with this story of a woman coming to grips with her violent nature.