At the end of World War II, a young woman stands on a hilltop in France and, as the sun bathes her in golden light, she says, “There will be days and days and days like this.” That image provides the last shot in “Plenty,” which is the story of how very wrong she was. The woman is Susan Traherne, a young English fighter in the French Resistance. She is not very seasoned and perhaps not very good at her job, but she stays alive behind enemy lines and she has a brief, poignant love affair with one of the men who parachuted down out of the night sky to fight the Germans.

The movie opens with her days in France. It follows her through the next 15 or 20 years, and ends with that painful flashback to a day when she thought the future held nothing but good things for her. But nothing else in her life is ever as important, as ennobling or as much fun as the war. She is, perhaps, a little mad. She confesses at one point that she has a problem: “Sometimes I like to lose control.”

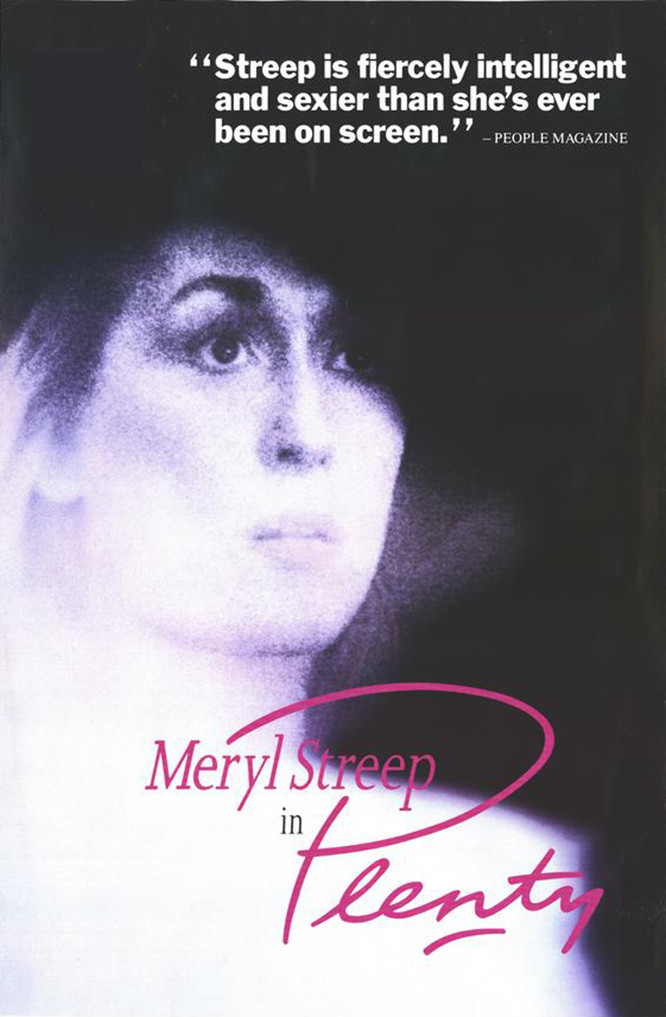

The movie stars Meryl Streep as Susan and it is a performance of great subtlety; it is hard to play an unbalanced, neurotic, self-destructive woman, and do it with such gentleness and charm. Susan is often very pleasant to be around, for the other characters in “Plenty,” and when she is letting herself lose control, she doesn’t do it in the style of those patented movie mad scenes in which eyes roll and teeth are bared. She does it with an almost winsome urgency.

When she returns to England after the war, Susan makes friends almost at once. One of them is Alice (Tracy Ullman), a round-faced, grinning imp who seems born to the role of best pal. Another is Raymond (Charles Dance), a foreign service officer who is at first fascinated by her free, bohemian life style, and then marries her and becomes her lifelong ennobler, putting up a wall of patience and almost saintly tolerance around her outbursts.

It is hard to say exactly what it is that troubles Susan. At first, David Hare’s screenplay leads us to her own interpretation: That after the glory and excitement of the war, after the heroism and romance, it is impossible for her to return to civilian life and suffer the boring conversations of polite society. Later, we begin to realize there is something a little willful, a little cruel, in the way she embarrasses her husband on important occasions, always seeking to say the wrong thing at the wrong time. Finally, we tend to agree with him when he explodes that she is cruel and brutish, and ungrateful for those who have put up with her.

But then there is an epilogue – a strange, furtive meeting with the boy, the parachutist, she made love with 20 years earlier. It is bathed in the cold, greenish-gray light of the saddest part of an autumn afternoon, and there is such desperation in the way they both realize that nothing will ever ever touch them again the way the war did. “Plenty” is finally not a statement about war, or foreign service, or the British middle class, but simply the story of this flawed woman who once lived intensely, and now feels that she is hardly living at all.

The performances in the movie supply one brilliant solo after another; most of the big moments come as characters dominate the scenes they are in. Streep creates a whole character around a woman who could have simply been a catalogue of symptoms. Charles Dance has a thankless role, I suppose, as her long-suffering husband, but manages to suggest that he is decent as well as duped. Sting plays a nondescript young man who unsuccessfully attempts to father her child. John Gielgud has three brief scenes and steals them all. The movie is written, acted and directed (by Fred Schepisi) as a surface of literacy and brittle wit, beneath which lives the realization that life can sometimes be pointless and empty and sad – and that there can be days and days and days like that.