Athletic dreams are universal: They transcend borders, ages, and social classes—and yet there are sometimes biases and prejudices tied up in who countries want representing them in international competitions. In the United States, this tension is playing out in the contrast between the “aggressively WASPy” Olympian outfits designed by Ralph Lauren and accusations against Team USA of systemic racism, as in the recent disqualification of runner Sha’Carri Richardson for ingesting marijuana in a state where the drug is legal. And in Iran, as captured in the revealing, intimate documentary “Platform,” that tension is between the modesty the Islamic republic demands from women, and the fierceness and determination it takes to compete at an elite level.

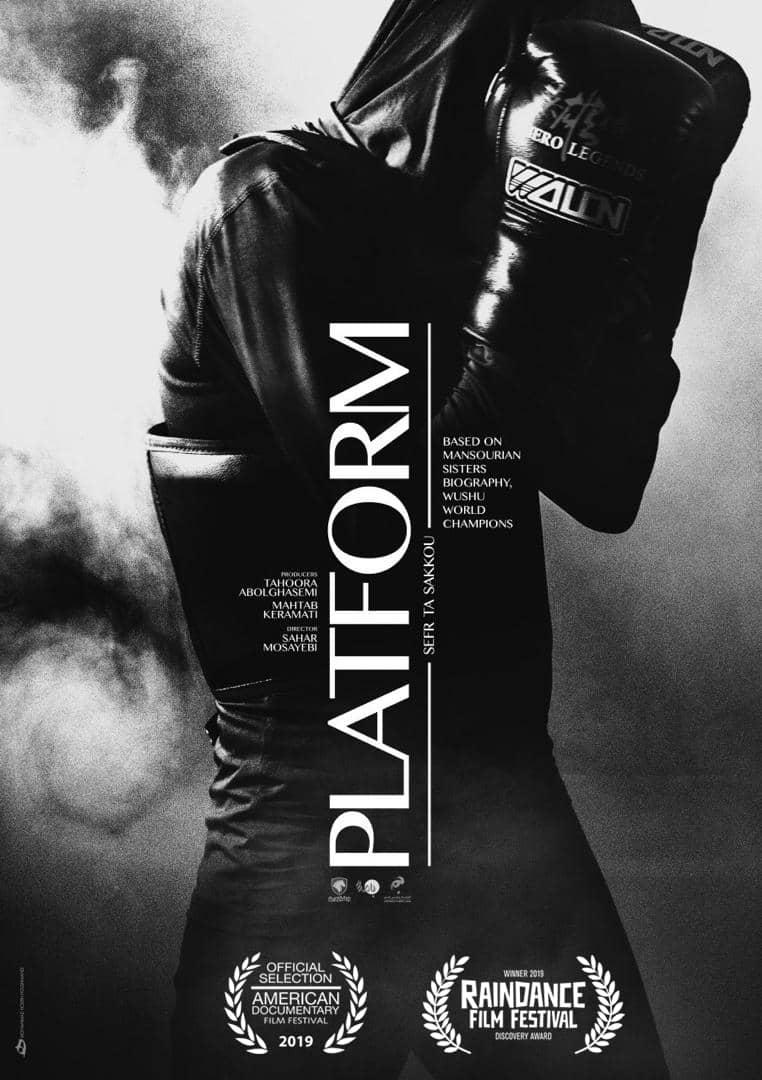

Director Sahar Mosayebi’s “Platform” follows three Iranian sisters as they train to become wushu champions. The martial art is popular in Iran, and Iranian athletes have won gold medals at the World Wushu Championships in recent years (and a few athletes have received bans after testing positive for steroids, a topic “Platform” does not cover). Rather than focusing specifically on the practices of the International Wushu Federation, “Platform” is a tighter portrait of thirtysomething sisters Shahrnaboo, Soheila, and Elaheh Mansourian, who hail from the Iranian city Semirom. They’re all top-tier competitors at sanda, a full-contact combat sport that combines elements of boxing, wrestling, karate, and taekwondo.

The sisters, who often bicker and tease each other, are all driven by competitive ambition, but have different personalities. Shahrnaboo is sarcastic and outspoken, a daredevil who likes to ride motorcycles and ride horses—and is the only sister who is married. Soheila is quieter and more reserved, and slightly cowed by not having the same numerous successes as Shahrnaboo and Elaheh. And Elaheh has a chip on her shoulder, and a frustration with the limited opportunities available in Iran for female athletes. “Wushu is not known in Iran, and neither am I,” she says, and her bitterness is palpable. When “Platform” begins in the months before the 2015 World Wushu Championships, all the sisters have won gold medals or held world titles in their separate weight classes—and they’re also struggling with the everyday economic and social frustrations of living in heavily sanctioned Iran.

In Semirom, the women are well-known. They’re recognized and treated with respect by practically everyone: construction workers, store owners, and women in long black chadors, sharing the sidewalk with the sisters in their white, blue, and red track suits from the Iranian team. On a larger scale, though, the sisters, their fellow wushu practitioners, and their coaches say that they’re underpaid and undervalued. State TV doesn’t show their matches, and they’re not given as much attention as male athletes. Their annual salary for being part of a competitive team is usually only $700 U.S. dollars. With that small amount, the sisters support their entire families—a recurring scene is someone in the family going to one of the sisters and asking if there’s enough money to pay a certain bill or fund a specific expense—and inside and outside the home, they’re under an immense amount of pressure to provide, and to conform.

Inside the home, a relative snarks about how a lost competition means that the sisters can’t underwrite the cost of an arranged-marriage engagement and wedding for one of their brothers (“You not only ruined your own plans, you ruined everyone else’s”). And outside the home, one of the documentary’s most revealing moments in terms of how fellows Iranians treat the sisters with a mixture of affection and traditionalism includes one of those aforementioned older women on the sidewalk scolding “Shahrnaboo, you look like a boy!” When Shahrnaboo good-naturedly asks, “What should I do?”, the woman’s response of “Wear black”—implying that she should settle down, stop sports, and become more pious and conservative—captures the contradictions here, and the simultaneous pride and chastisement these sisters regularly face.

As is traditional in Iran, eldest sister Shahrnaboo lives with her husband Omid, while middle sister Soheila and youngest sister Elaheh live with their mother. Each day involves some mixture of housework—Shahrnaboo cooking for herself and Omid; Soheila and Elaheh helping clean and prepare food for their mother and other unmarried siblings—and intense training both at a women-only gym and in the countryside. In the gym, the trio encourages each other and spars brutally with each other, throwing heavy kicks that thwack against the pads the sisters variously hold; Shahrnaboo in particular talks a big game. In the country, they run up hills, give each other piggyback rides through lush fields, and hold elastic bands around each other to increase the resistance of their punches and kicks.

Interspersed throughout these hard-hitting, spryly edited training sequences are interviews Mosayebi did with each woman about their interest in wushu, their childhoods, and their dreams for the future. Some aspects of the women’s histories and personalities are better contextualized than others. The sisters talk about how their athleticism was built from growing up in poverty and becoming hardened by a father who put them through the wringer: “We did a lot of men’s work.” A revelation about their relationships with their parents is achingly understated, and helps explain some of their drive to succeed. Also well-handled is mischievous Shahrnaboo’s relationship with her husband Omid, himself a former wrestler. Omid is a fascinating figure who is aware of Iran’s patriarchal society and knows that he’s falling prey to it when he complains about the long months during which Shahrnaboo is away, but who also refuses to ever stop his wife from doing something she loves. The scenes of them together are obviously raw, as are the sisters’ reactions to various failures, in particular an agonizing moment during which one of the sisters, after being rejected from Iran’s national wushu team, goes home and asks their mother why her prayers for success didn’t work.

All of this adds up to an engrossing slice of life, like the recent “Sisters on Track,” also about a trio of sisters rising to high levels of athletic competition. What is lacking in “Platform,” though, are the details of what happened to the Mansourian sisters after the 2015 and 2016 wushu championships in which they competed. A closing intertitle card shares the sisters’ ages, international wins, and that they have left Iran, but doesn’t give any additional information about what they’ve done since, and doesn’t feature any recent interviews. Have they kept competing? If not, how are they adjusting to life without sports? In doing more research after watching “Platform,” I read a news story about how the sisters were punished by the International Wushu Federation for speaking out about steroid use in the sport and preferential treatment for certain athletes by the Iranian government. None of this is featured in “Platform,” either. That’s not to imply that the documentary isn’t captivating enough in its current form. But its truncated ending, and the sense that there is far more to this story than what “Platform” includes, puts a damper on the otherwise-engaging documentary.

Now playing in select theaters.