We forget a lot of things when we grow up. One of those things is how slowly time seemed to pass during childhood. Back then, the days were permeated with impatience as we awaited the arrival of adulthood, completely unaware that the semblance of a slog would be replaced by a speeding up of time as we hurtled toward death. Even when the day was full of adventure, or we were preoccupied with some project or media, there were pockets of silence and boredom, moments that were simply filled with dead air. Time goes by so slowly. Until it does not.

Writer/director Céline Sciamma’s superbly acted “Petite Maman” understands this forgotten notion. So many films about children fear even one moment to savor the mundane elements of life. The pacing here is deliberate, but never invites boredom. At barely 72 minutes, it breezes by before we realize how deeply it has implanted itself in our memory. There are heavy topics present here, the death of a parent, childhood illness, grief, and the guilt one feels when unfinished business exists with the deceased. But they exist within an aura of the fantastic that elevates them from a level of unbearable pain to a more comforting area of bittersweetness.

“Petite Maman” also acknowledges another idea that evaporates from the mind once it reaches maturity: the notion that something truly magical can not only happen but can be accepted at face value. Our protagonist, Nelly (a magnificent Joséphine Sanz), discovers something incredible in the backyard of her mother’s childhood home, and rather than interrogate it with skepticism, she simply runs with it. The inkling that something enlightening may occur intrigues her. She’s at the age where an imaginative outcome remained unspoiled by the chafing of a forced suspension of disbelief. Sciamma trusts us to go with Nelly now, and to ask questions later, if at all. Those looking for explanations of what happens here will be sorely disappointed.

Sciamma employs the same visual storytelling she used in her prior feature, “Portrait of a Lady On Fire.” She informs us of the close relationship between Nelly and Marion (Nina Meurisse) in the scene where the two are en route to Marion’s old residence. The camera stays focused on Marion, with Nelly’s hands entering the frame to feed her a lunchtime snack. The action repeats itself numerous times, more than we’re expecting. It’s almost comical, these little hands feeding a grown woman in a reversal of a common mother-child activity. Then Sciamma unexpectedly goes for your heart: Nelly’s arms embrace her mother’s neck for several beats before the scene ends.

Marion is making the trip to clean out her mother’s home. When “Petite Maman” opens, we are informed without plot exposition that her mother has passed. Nelly walks through what appears to be a senior citizen’s residence, saying goodbye to several women before entering an empty room where a cane resides. Sciamma is setting us up for the moment later in the film where we see that cane in use by its owner, and it’s not in a flashback, either. “I didn’t get to say goodbye,” Nelly tells her mother, who informs her that she always said goodbye as part of the ritual we’ve just seen her perform. “But the last goodbye wasn’t good,” Nelly says.

That line hits hard. No goodbye can be good enough where death is concerned, because it’s the last one and there are no do-overs. It’s no surprise that Nelly will get another chance to perfect her farewell, but Sciamma resists the urge to overplay it. Sanz plays it without aiming for perfection; it’s merely just another chance to say the same goodbye. There’s such fragile beauty in the mere thought of the opportunity. “Petite Maman” is full of scenes like this, scenes that aim for a casual nonchalance that allows the viewer to absorb them without a telegraphed emotion. It allows you to fill in the blanks.

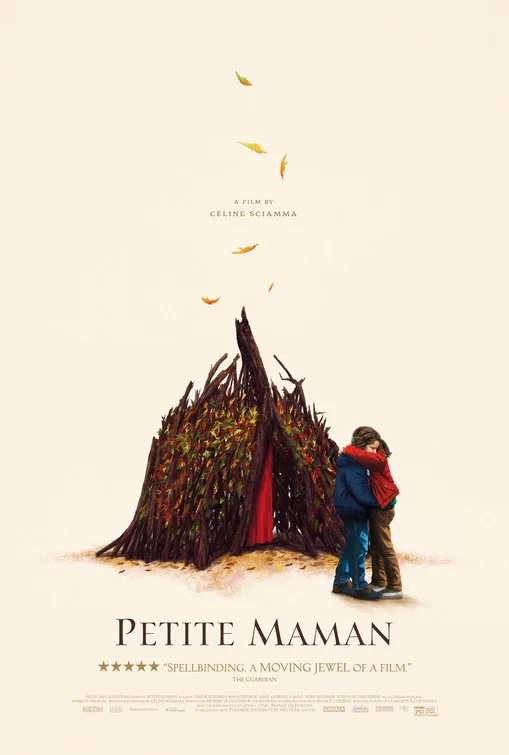

Sciamma uses Nelly’s grandmother’s death as a jumping off point for her tender investigation of mothers and daughters. Like Nelly, we do not know much about Marion’s childhood nor her relationship with her Mom. When Nelly asks her father (Stéphane Varupenne) about the forest fort/treehouse Marion built as a child, Marion dismisses the enterprise as “child stuff” that doesn’t warrant any interest. “I am interested,” says Nelly. “I am a child.” It’s a reminder to her mother and to us; soon after, we are immersed in the fable the director spins for her protagonist. Nelly accepts each flight of fancy not because she is gullible or lacks any skepticism, but because her age allows her the unfiltered capacity to believe.

While in the forest surrounding her grandmother’s house, Nelly discovers a similarly aged little girl (Gabrielle Sanz) building a fort. Her name is Marion, just like her mother, and she bears more than a passing resemblance to Nelly. (The two actors are sisters.) When Marion invites Nelly home, she brings her to the same house Nelly left when she entered the forest despite not following the same path. Watch Sanz’s surprised reaction when she presses the part of the wall that revealed a secret door earlier in the film. She figures this jump to the past rather quickly, and after an initial hesitation, decides to pursue wherever this adventure takes her.

What’s most refreshing about “Petite Maman” is that it doesn’t play coy with its magic, nor does it separate it from the sadder, darker reality that surrounds it. Nelly tells the young Marion that she is her daughter, and that she knows the surgery Marion will be undergoing the next day will have its repercussions but will also serve the purpose of keeping her from the affliction that caused her mother to use that cane. Rather than ask how the two wound up on the same timeline, young Marion asks for more information. The two bond in ways that the adult Marion and her child simply cannot. They play games, and we see the similarities between the two. Imagine if you knew your parent as a kid, the film asks, and the possibilities haunted and intrigued me long after the film was over.

I am so much like my own mother, and she is very much like her dad, who died when I was 18 months old. Many days I have wondered that, If I’d known him better, I’d know mom better, and by extension, I’d understand myself. “Petite Maman” inspires that kind of feeling, and does so in a fashion that is simple on the surface, yet commendably complex upon introspection. When Nelly and the adult version of Marion see each other at the end, the result is emotionally overwhelming, even more so when you realize that the film accomplishes this catharsis with two words. These two are rediscovering themselves. We forget a lot of things when we grow up. This film is a wonderful reminder.

Now playing in theaters.