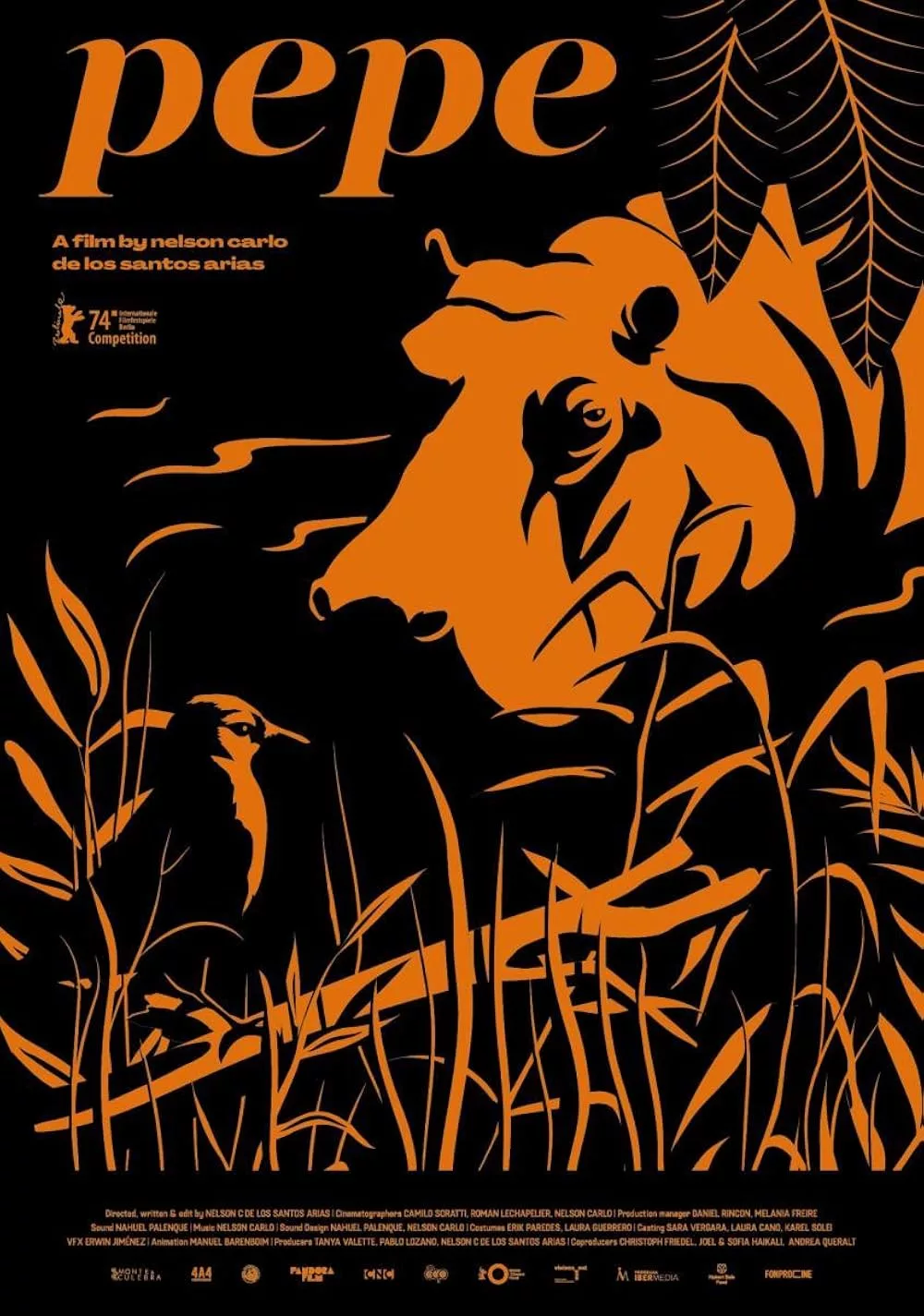

Guttural sounds permeate the landscape before an ominous voice takes over. Both belong to an enormous creature, a hippopotamus about to share the uprooting that landed his parents in Colombia and which resulted in his untimely death at the hands of men in 2009. In “Pepe,” a formally imaginative and thought-igniting experimental docufiction, Dominican director Nelson Carlo de Los Santos Arias molds the real-life events around the hippos imported by notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar into an exciting, visually unpredictable consideration of colonialism and human hubris tinged with the fantastic.

While the name of the famed pachyderm comes from the paramilitary group Los Pepes, the filmmaker visually links it to the 1960s Hanna-Barbera cartoon “The Peter Potamus Show,” whose hero is known as Pepe Potamus in Spanish-speaking Latin America. The ordeal began in the late 1970s, with a German tour group visiting what was then known as South West Africa, a former colony of South Africa (or Rhodesia), today the independent country of Namibia. A German tour guide dismisses his local employee’s explanation of how traditional beliefs regard a hippopotamus as an omen of bad news. The tourist couldn’t care less as long as they can get their photos of these exotic beasts to bring back home.

Underwater footage of hippos in their natural habitat gives way to the shadow of helicopters resting on rocky, arid landscapes as the animals are taken from their ancestral land and transported into the unknown. Pepe’s commentary during this segment instantly calls to mind French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop’s documentary “Dahomey,” in which she gives voice to African works of art once stolen by European invaders to speak about their repatriation. Both “Pepe” and “Dahomey” premiered last year in competition at the Berlin International Film Festival suggesting both artists tapped into the same narrative wavelength to address similar themes around complex geopolitics.

By exploring the power dynamics within the community of Colombian-born hippos—the offspring of those Escobar brought to the Americas—as they become attached to the only land they’ve ever known, Los Santos Arias draws parallels between the animal kingdom and behaviors in “civilized” societies. Pablito, one of Pepe’s siblings, named after Escobar because of his ruthless use of violence to maintain power as the pack’s alpha male, exemplifies these unsavory similarities across species. But once Pepe is banished from the herd, the film loses contact with him for a substantial amount of time rather than submerging its cinematic paws fully in his preoccupations with existence, the familial feuds that burden him, and sharp observations on his diasporic worldview.

That four actors voice Pepe as his narration switches languages throughout— Jhon Narváez in Spanish, Fareed Matjila and Harmony Ahalwa in Afrikaans, and Shifafure Faustinus in Namibia’s Mbukushu—reads like a sonic manifestation of the distinct identities the animal holds within his body despite being forced to be born away from his native land. Early on, Pepe ponders its consciousness and its ability to understand human tongues; still, Los Santos Arias ensures his snorts are a distinctive element in the film’s rich soundscape (the director, who served as his own cinematographer for most of the shots, is also behind the upbeat score). 16mm footage, animation, and striking aerial sequences constantly interact to form a filmic language that’s both expressive and erratic for powerful effect.

Killing Pepe for being perceived as a danger when he and his kind would have never reached this far-flung land if it weren’t for mankind’s selfish intervention is downright perverse. The hippo is punished for acting instinctively to survive the circumstances his oppressor has imposed on him. In turn, as a late montage implies, violence against those with Indigenous features or Afro-descendants in a country like Colombia or the director’s own Dominican Republic (on the same island as Haiti) is obscene. The population in the region is the direct result of genocide and the monstrous human trafficking on which European powers built their blood-drenched empires.

Pepe surfaces as one more victim of the same illegitimate appropriation of life. What gives humans the right to remove fauna from its home simply to fulfill a desire to own it or to limit its freedom? Escobar’s deathroll responds to the same power-hungry, self-centered motivations. The perpetrator justifies their crimes as necessary to their ambitions.

Pepe makes for such a fascinating protagonist; when Los Santos Arias digresses to the drama of the men and women living on the shores of the Magdalena River, whose conflicts partially derived from Pepe’s presence, one can’t wait to hear the hippo’s ruminations on the life he’s led in these foreign waters before it was cut short. That long stretch, focused on local fisherman Candelario (Jorge Puntillón García) and his wife Betania (Sor María Ríos), brings “Pepe”’s middle section back into commonplace storytelling ground, and away from the free-flowing rhythms that entrance at both ends of the running time.