“So I grew up completely ignorant that my heritage, my culture, my education, my life and soul had been kept overseas for centuries.”

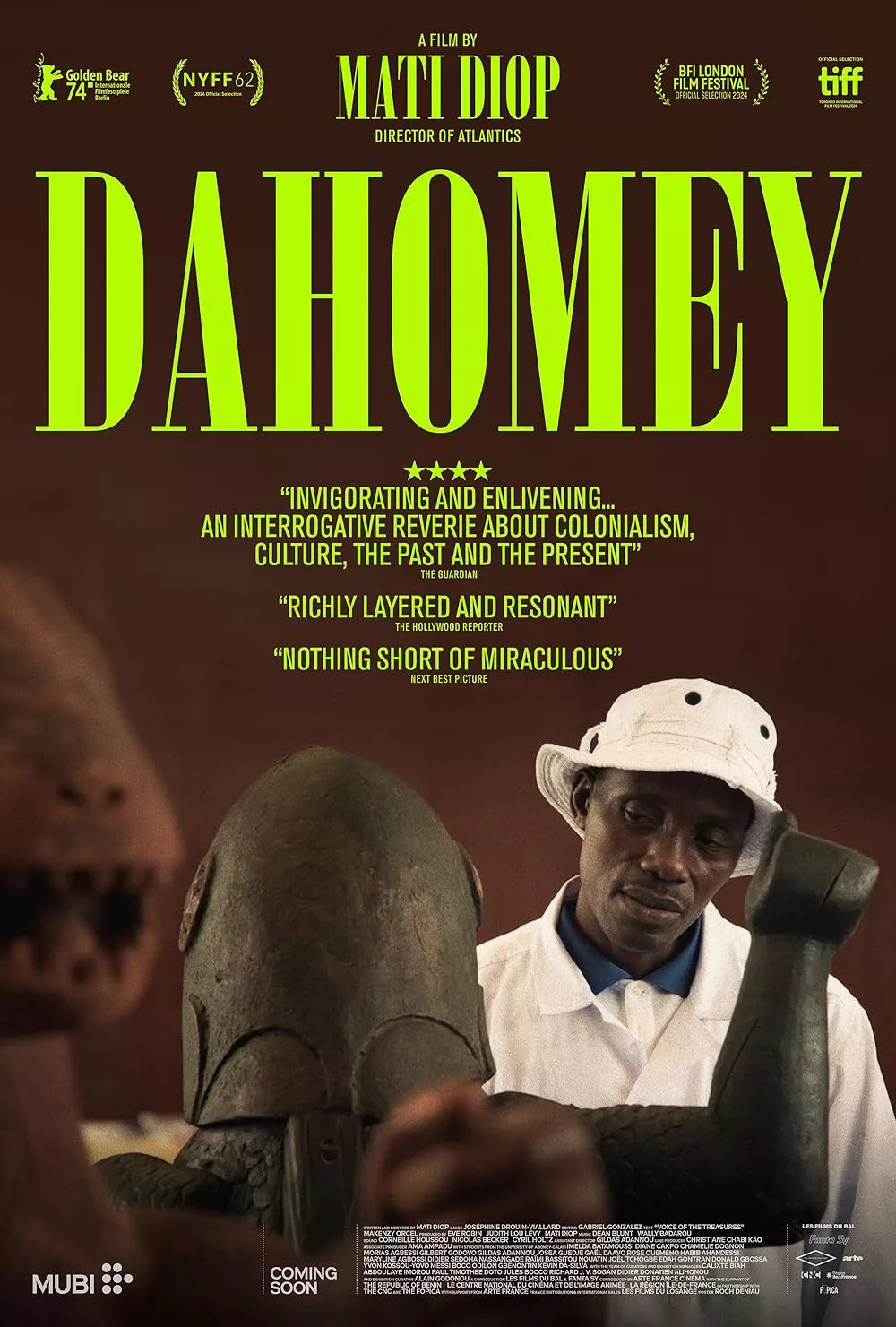

Mati Diop’s feature documentary “Dahomey” is filled with quotes just like the one above. The film depicts the return of 26 royal treasures from the Kingdom of Dahomey, which was established in the 17th century. In late 2021, the artifacts were transported from museums in Paris back to their place of origin, The Republic of Benin. “Dahomey” is a film about reckoning with history that has been forever altered by colonialism. French troops originally seized the artifacts after war broke out between them and the Kingdom of Dahomey, in 1892. Like most colonial bodies, France inflicted both physical and cultural violence against the people of Dahomey, robbing them of their history to add insult to injury. The current state of Africa has been largely shaped by European interference, from language and education to the state of their cultural institutions.

Much like her narrative feature debut “Atlantics,” “Dahomey” blurs the line between life and death. Giving voice to one of the returned artifacts, Diop imbues the documentary with the feel of a ghost story. The artifact, known only as 26, is a carved statue of wood and metal that observes its own journey from France back to its homeland in Benin. Its voice is low and raspy, reflecting its age and hidden wisdom. At some points, Diop shoots from the perspective of 26. When it is packed up into a crate, we’re right there with it, watching as the light disappears. We are transported from France to Benin with 26, which goes from being carried by white, French museum workers to being held by its one people, with skin dark and beautiful. We, like 26, are more at ease in Benin, knowing that a wrong has finally been righted.

But then comes the discussion and debate among the community as they grapple with the hole that the loss of their history had created for centuries. “Dahomey” is at its most compelling when simply observing the process of accepting and evaluating reparations, all the while knowing that there’s still a very long way to go. Thousands more artifacts remain in France, with no guarantee of when they’ll be making their way back to the homeland. Some people are full of optimism while others feel like the damage is permanent, their identities forever tied to the people who tried to conquer them. Diop’s camera doesn’t judge the conversation, choosing instead to observe it lovingly, encouraging dialogue on and off screen. While not fully chronicling the long process of recovering the artifacts, their journey is deeply felt by the people, and watching them highlights the pain of what has been lost to them. History and the self are inherently connected, both informing the other. To confront historical injustice is to confront the often fractured nature of identity, with all the pieces spread across the world, often in the path of war. The people of Benin have only begun long process of redefining who they are in the world now.

With its slim 68-minute runtime, “Dahomey” feels a tad too short. Once the film gets into its rhythm, the conversations are so engaging one wishes they would go on for much longer. To be Black anywhere in the world is to constantly be discussing and renegotiating the details of history. The boot of imperialism has left its mark on us all and the greatest defense we have against it is to keep talking about it. Progress is not as simple as getting our things returned to us, it’s also about recognizing and refusing to excuse cultural violence that seeks to erase history and craft society in the image of oppressors. Diop uses “Dahomey” as a form of cinematic activism, using the medium to force us to look closely at the past to craft a better future for oppressed people everywhere. Beautiful, melancholy and intellectually stimulating, “Dahomey” is a documentary that should be seen by all.

This review was filed from the New York Film Festival. It opens on October 25th.