The musician’s name is Maury Dann and he’s perhaps on the edge of stardom and certainly on the edge of an abyss. He started in life as next to nothing and by the age of 35 has worked his way up to his own band, a couple of hit records, string of groupies and a chauffeured Cadillac limousine. “You only pass through life once,” he is fond of saying, “and it might as well be in a Cadillac.” He does not realize he is pronouncing his epitaph.

He more or less lives in the back seat of his Cadillac. He’s on the way to Birmingham, and then to Nashville, where he has a booking on the Opry and a sure guest shot on Buck Owens and — maybe — a chance of getting on the Johnny Cash show. Those are his destinations, but they seem somehow insubstantial as he relentlessly moves at 95 miles an hour through an endless Alabama. He isn’t basically a cruel man, but you would have a hard time proving that by anyone who knows him. He lives on Cokes and Dr. Peppers and handfuls of pills, and there are times when he’s so strung out that it must be physically painful for him to appear to be present.

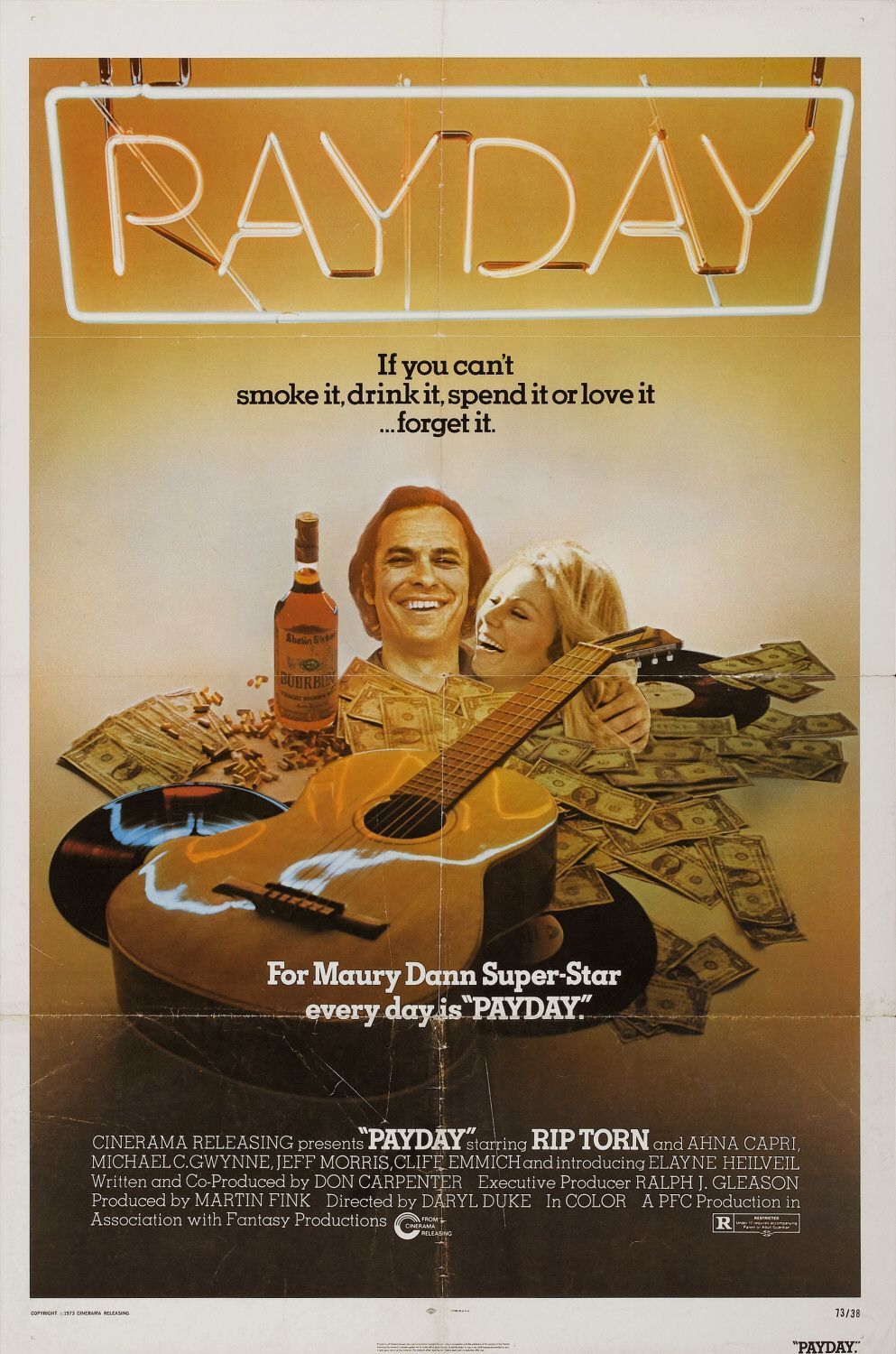

He’s played by Rip Torn in Daryl Duke’s “Payday,” which was released in 1973 to some very favorable reviews and then, inexplicably, never got a proper national release.

It’s interesting that “Payday” comes along on the heels of Robert Altman’s “Nashville,” because Maury Dann could have wandered through “Nashville” and fit right in: He’s cut from the same cloth as the singers in that movie, but he’s a little more desperate. The pills are keeping him alive and killing him, all at the same time, and his life is filled with great terrors. He tries to distract himself by expeditions back into his past, where he apparently felt some pleasure, but when he arrives for the birthday of one of his children he finds that he is either four months late or eight months early, and when he joins old friends for some quail-shooting the day ends in a fight over a dog.

The movie’s structure qualifies it as a fairly traditional road picture; we get the series of little towns and sunsets and traffic signs and motels and fast food joints that look about the same in Alabama as anywhere. But the stops along the way are a lot more perceptive than they usually are in road movies, and in particular there’s an encounter with a disk jockey that develops genuine corruption.

Maury, acting as straight as he can despite the speed, visits the DJ in his studio and brings along a quart of Wild Turkey as a gift (“Why, Maury, I see you’ve brought me some wild game!” the DJ snickers). Then follows low-key blackmail in which the DJ tries to talk Maury into returning on Monday for a local fund-raiser, and Maury tries to talk his way out of it, and they both implicitly acknowledge the payola aspect of the whole deal. It’s a perfectly observed scene.

There’s another sequence in which Maury dumps one of his groupies at roadside, drives off, returns, drives off again and then returns again; to describe exactly what he’s up to would destroy the scene, but it’s funny and very hurtful both at once. Duke uses these road scenes to build up a portrait of a man who is deeply cynical, especially about himself, and who uses his little power to protect himself from a world which has so much more. In the end, it turns out he isn’t powerful enough.

There’s a murder — quick, accidental, almost a surprise — and Maury gets his driver to take the rap for him. It’ll be self defense anyway, but Maury has to make the Birmingham concert. And then his life starts closing in on him. His problems refuse to stay buried; his desperation turns into rage; he has come to the end of the line and he can’t fix things anymore — “Not this time,” his manager says, when he tries to get rid of a cop. The movie’s ending provides not so much a tragedy as a deliverance for Maury, and “Payday” is very good at making us see why.