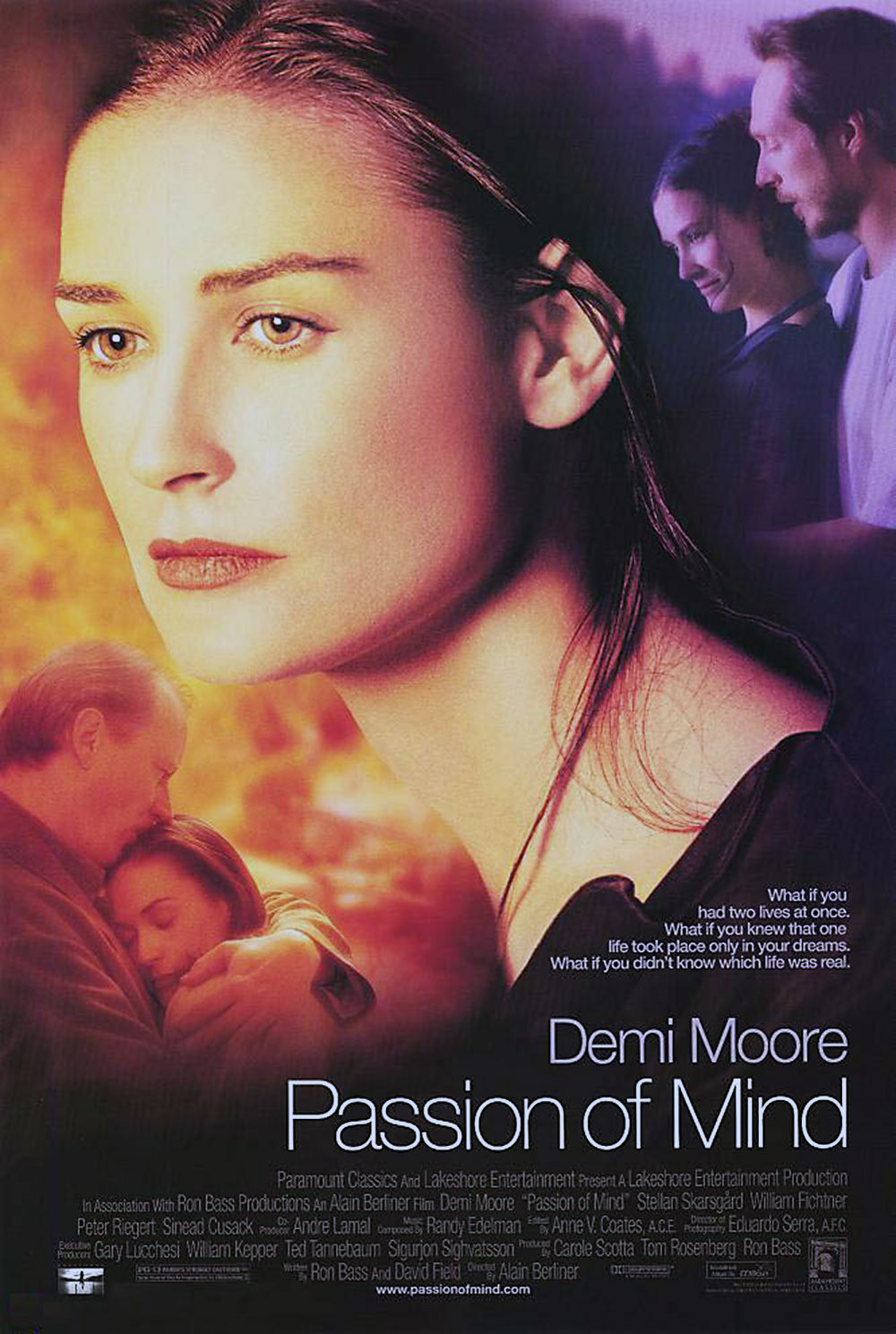

When Marie is asleep in France, Marty is awake in New York. When Marty is asleep in New York, Marie is awake in France. Both women are played by Demi Moore in Alain Berliner’s “Passion of Mind,” a film that crosses the supernatural with “an interesting case of multiple personality,” as one of her shrinks puts it. She has two shrinks. She needs them. She doesn’t know which of her lives is real and which is the dream. Whenever she goes to sleep in one country, she wakes up in the other. Multiple personalities are bad enough, but at least she doesn’t have eager kidneys; getting up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom could lead to schizophrenic whiplash.

The movie uses its supernatural device to show Moore’s characters living two contrasting lifestyles. In France, she leads a quiet life as a book reviewer and rears her two daughters. In New York, she’s a powerful literary agent who dedicates her life to her career. In France, she meets William (Stellan Skarsgard). In New York, she meets Aaron (William Fichtner). They both love her. Each of her personalities, Marty and Marie, is aware of the other and remembers what happens in the other’s life.

Like “Me Myself I,” the recent movie starring Rachel Griffiths, this movie is about a woman’s choice between family and career. In the Griffiths film, a busy single writer is magically transported into a marriage with a husband and three kids. If she could have led both lives at once, as Marie/ Marty does, I think she would have been OK with that. And as Marty and Marie trudge off to complain to their shrinks, I was wondering why it was so necessary to solve their dilemma. If you can live half of your life quietly in France and the other half in the fast lane of Manhattan, enjoy parenthood and yet escape the kids, and be in love with two great guys without (technically) cheating on either one–what’s the problem? When you’re not with the one you love, you love the one you’re with. If it works, don’t fix it.

Of course it doesn’t work. If one of the worlds is real and the other is a dream, and if you cannot be in love with two men at once, then what happens if you commit to the dream man and lose the real one? This preys on the mind of Marie/Marty, who also dreads what could happen if the two worlds mix in some way. She won’t let one guy spend the night, because “if someone were to be with me and wake me up, something bad might happen.” It is that very problem that the movie never quite solves logically. Forgive me for being literal. The time difference between New York and France is six hours. How does that fit into your sleep schedule? If she is awake until midnight in France, does that mean she’s asleep all day in New York, and wakes up at 6 p.m.? Are there 24 hours in a day for both characters? These questions are cheating. Forgive me for thinking of them. They obviously occurred to the screenwriters, Ron Bass and David Field, who just as obviously decided to ignore them. The movie is not about timetables but life choices, and to a degree it works. We see Marie/Marty pulled between two worlds, in love with her children, attracted to the two guys. The problem is, that’s it. We master the situation in the first 40 minutes, and then the wheels start spinning. What’s needed is a way to take the story through some kind of U-turn.

Why not have the woman accept her situation, work with it, willfully experiment with her two lives, self-consciously engage with it? Don’t make her a victim but a psychic explorer. Why, if we are dealing with a woman who is liberated half of the time from each lifestyle, does the movie fall back on the tired formula that there is something wrong with her, and she must seek psychiatric help to cure it? The joy in “Me Myself I” is that the woman self-reliantly deals with the vast change in her life instead of diagnosing herself as a case study.

Another difficulty in “Passion of Mind” is with the men. Skarsgard and Fichtner bring more to the movie than is needed. These are complex actors with subtly disturbing undertones. They both play nice guys, but we can’t quite believe them. We suspect secrets or hidden agendas. They smile, they’re warm and pleasant and supportive, and we’re wondering, what’s their angle? For this particular story, it might have been better to cast actors who were more bland and one-dimensional, so that they could represent only what is needed (two nice guys) rather than veiled complications.

Demi Moore does what she can with a screenplay that doesn’t seem confident about what to do with her. She is convincing as either woman, but not as both, if you see what I mean. She makes a wonderful mother in France and a convincing businesswoman in Manhattan, but when she is either one, we wonder where she puts the other one. The screenplay doesn’t help her.

By the ending of the film, which is unconvincingly neat, I was distracted by too many questions to care about the answers. The structure had upstaged the content. It wasn’t about the heroine, it was about the screenplay. In “Me Myself I,” which has a much simpler premise (the woman goes from one life to another with an unexplained magical zap), there was room for a deeper and more human (and humorous) experience. First the heroine was one, then the other. In “Passion of Mind,” by being both, she is neither. Is her problem a split personality or psychic jet lag?