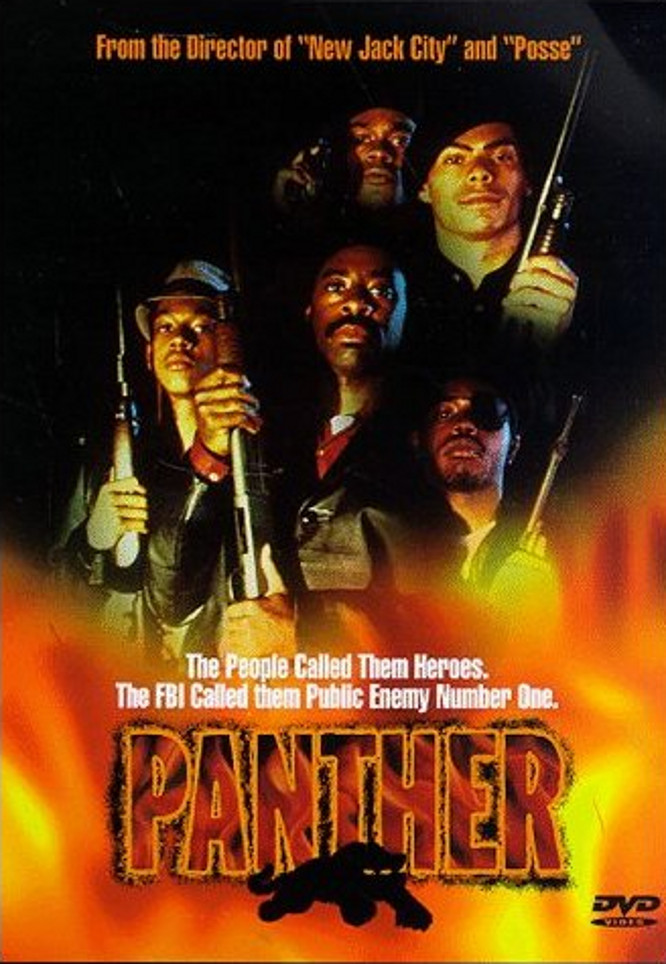

Mario Van Peebles‘ “Panther” is the story of the rise and fall of a 1960s black radical movement that captured the imagination of its time. Memoirs by its founders and others have suggested that the Black Panthers never had the power or numbers they claimed, but they served a historic purpose, creating the image of an armed, militant “self-defense” group that was an alternative to the nonviolent philosophy of Martin Luther King.

The Panthers grew famous as the civil rights movement of the early 1960s was losing momentum after the assassination of King.

Their message was clear: White America could no longer count on pacifist blacks to patiently hold nonviolent marches; what was coming, as James Baldwin warned, was “The Fire Next Time.” News photos of Black Panthers, armed with rifles, patrolling the streets of Oakland or entering the California State Assembly, were among the key images of the time.

There is a fascinating study to be made of the Black Panther Party. “Panther” is not that film. Superficial and confusing, it cops out at the end with a fictitious thriller climax involving the Mafia, the FBI, drugs, chases, fires and explosions – as if the reality of the Panther’s battles with the police weren’t enough.

“Panther” does a good job, however, of capturing the idealism and excitement of the party’s early days. A narrator named Judge (Kadeem Hardison), a fictitious composite, tells us that the Panthers were more or less dreamed up in a coffee shop by Huey P.

Newton and Bobby Seale, whose press coverage acted as a nationwide recruitment and publicity machine. In the early days revolutionary rhetoric alternated with improvisation, as when the Panthers paid 30 cents for Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book in Chinatown and sold it to white Berkeley students for $1.

Those heady days, part of the Summer of Love, were soon ended, as the Panthers began to feel the pressure of the FBI. Its chief, J. Edgar Hoover, could not believe young blacks were capable of running such an organization, and he suspected that communists were behind it – as, indeed, he suspected they were behind everything. He infiltrated them with double agents such as Judge and ordered local lawmen to set them up for phony arrests. Soon the whole enterprise became deadly and dangerous, and Newton ominously quoted the Spanish Civil War leader Delores Ibarruri: “It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees.” Newton, played by Marcus Chong, is well-read and articulate, forever informing the police of his rights. One of those officers is Brimmer (Joe Don Baker), who angers the FBI when he observes that the Panther’s rhetoric “sounds like the Constitution to me. With maybe a little bit of the Bill of Rights thrown in.” Brimmer, who is alternately evil and insightful at the convenience of the plot, eventually runs the infiltration of the Panthers.

Newton and Seale (Courtney B. Vance) run the Oakland Panthers (the film’s focus) more or less as equals, realizing they should not show up together at too many events lest the police realize how small the group really is. Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver (Anthony Griffith) arrives on the scene at about the time Newton is jailed on a frame-up, and is less of a strategist, more of an instigator: “You gotta sit on Eldridge,” Newton tells Seale.

The movie’s first 90 minutes are a vivid period reconstruction of the way the Panthers grew both through community programs (they fed thousands of children from their storefront centers) and through a canny manipulation of the media. It makes a compelling story. But the climactic scenes of the movie are fabricated. We see teletype printouts, presumably from Hoover, ordering the “ultimate conspiracy.” This is an alliance between the FBI and the Mafia to flood the ghetto with cheap drugs. It is a convenient fiction in the movies that the Mafia can do anything, but this plot point is sloppy right down to the wording: Would Hoover refer to his own plan as a “conspiracy?” Mario Van Peebles has said there is no evidence that the FBI plotted to weaken the party by flooding Oakland with heroin. Although the “ultimate conspiracy” makes a convenient plot point, it does a disservice to young people who want to understand what really happened. The Panther’s end came through exhaustion, through the imprisonment or exile of their best leaders, through the harassment of the FBI, and because some members became disillusioned by the questionable activities of others. They weren’t done in by the godfathers.

But that wouldn’t have made an exciting ending. Instead, Panthers dodge behind crates as bullets whiz by, and a courageous martyr sacrifices his life to destroy the Mafia’s drugs. The action ending is a copout, underlining the superficial way the characters have been treated.

Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X,” dealing with related material at about the same time, does a much better job of making its characters three-dimensional and getting us involved with them. Since “Panther” is told from the conveniently omniscient point of view of Judge, who is fictitious, I never got a real feeling for Seale and Newton as human beings.

At the end of the film, we are informed, “Before the Panthers were crushed, they had succeeded in establishing chapters in almost every state.” There’s the real story – how they did it, who they were, how they were crushed. That’s the movie still to be made.