Three teenage girls, three possible futures. During a hot August in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, they hang out together, talk about boys and clothes, and attend band practice. One will get pregnant. One may drift away from these friends and find a new crowd. One may go back to school, even though the local school has been closed (asbestos problems) and that means three hours on the bus every day. The theory is, their marching band may be sponsored for a trip to Alaska, a prospect that more or less brings conversation to a halt, since they are at a loss for opinions about Alaska one way or the other.

“Our Song” is the new movie by Jim McKay, whose “Girls’ Town” (1996) was also about adolescent girls making their plans. I admired that film, and I like this one more, perhaps because the actors are closer to the ages of the characters and seem to inhabit their lives more easily. “Girls’ Town” felt the need to have a plot. “Our Song,” like “George Washington,” has the courage to work without a net, aware that when you’re a teenager, your life is not a story so much as a million possible stories.

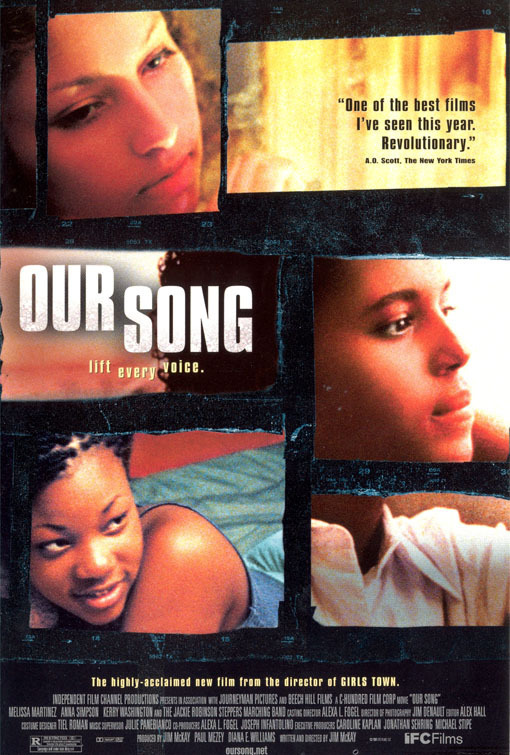

The movie stars Kerry Washington, Anna Simpson and Melissa Martinez, all in their first roles, and it’s impossible not to think a little of “Mystic Pizza,” which introduced Lili Taylor, Annabeth Gish and Julia Roberts. I have a feeling we’ll be seeing these newcomers again; indeed, Washington, who has a face the camera loves, has already made “Save the Last Dance” (as the white girl’s new best friend) and “Lift” (a Sundance hit, still unreleased, where she plays a shoplifter).

In “Our Song,” Washington is Lanisha, with a divorced black father and Hispanic mother. She’s a good student, has plans, lives in a neighborhood where dying young is a fact of life; she says she “sometimes thinks about being shot, like it would be OK.” But then she snaps out of it and decides, “Today’s a good day.” Simpson plays Joycelyn, who has a job in retail and is beginning to bond with the other clerks at work. They begin to seem cooler to her than her old friends, and having a paycheck and money to spend seems cooler than going to school; she doesn’t see yet that employment at that level is a life sentence.

Martinez plays Maria, whose boyfriend Terell (D’Monroe) says he wants to break up. Her friends’ theory: He’s just trying to get out of buying her a birthday present. She discovers she is pregnant and tells her boyfriend. “I’ll be around,” Terell says, although he clearly prefers spending time on the streets with “my boys.” Maria is realistic: “You barely act like you like me now.” The sad truth is, she will probably have this baby and set the course of her life out of misplaced love for an indifferent boy who is already on his way to the exit door.

There is a counterpoint to her decision. Eleanor (Kim Howard), a young local girl with a baby, takes her child in her arms and jumps out of her project window. Friends and neighbors gather at a makeshift shrine of flowers and Polaroids, giving Eleanor the attention now that she needed yesterday.

The thread connecting the girls’ lives is their marching band, the Jackie Robinson Steppers. It is a real band, something we don’t have to be told after we see them. I learn that McKay got the idea for his film when he saw the Steppers in a parade, and began to wonder about the lives of some of its members. The band provides a focus, discipline, pride. It is very good. And the bandmaster provides a friendly but firm male presence for young people who often come from fatherless homes.

Interesting, the differences between this film and “crazy/beautiful,” another new film about young people about the same age. Both are good movies. “crazy/beautiful” has an established star (Kirsten Dunst), more plot, a more showy and entertaining sort of angst. It seems more sure of exactly what it wants to tell us. “Our Song” is not on the same fast track; it ambles, observes, meditates, has patience. Most audiences will connect more with “crazy/beautiful,” which does the lifting for them. “Our Song” requires us to look and listen to these girls, and make our own connections.

Example: Lanisha, the Kerry Washington character, has asthma. One day she starts to have an attack, and her friend takes her to the emergency room, where the receptionist of course exhibits the usual blindness toward a health crisis while demanding insurance forms, identification and so on. In a different kind of film, this scene would have built up into a dramatic climax–“E.R.” lite. “Our Song” knows that things like this happen every day, that Lanisha will be frightened but will survive, that life goes on, that emergency rooms are more familiar to teenage girls from this neighborhood than to Kirsten Dunst’s friends in Malibu.

“Our Song” is content with the rhythms of life, and so performs one of the noble functions of the movies, which is to give us the opportunity to empathize with characters not like ourselves.

Note: Because “Our Song” deals with the daily reality of many girls under 17, it has been rated R by the MPAA, so that they can be prevented from learning from the movie’s insights.