Fernando is a writer who returns home to Colombia to die. By the end of Barbet Schroeder’s ”Our Lady of the Assassins,” he is almost the only person he knows who is still alive. His hometown is Medellin, company town of the cocaine industry, seen here as a cursed city of casual death, where machine-gunners on motorcycles roam the streets settling gang feuds.

The writer knew this town 30 years ago, when it must have been a beautiful place. Now killings are common, bystanders look the other way, and in the movie (at least) the police seem absent. Fernando (German Jaramillo) has arrived at a time in his life when he hardly seems to care: Did he come home half-expecting to find death before it found him? A homosexual, he goes to a male brothel and meets Alexis (Anderson Ballesteros), a teenage boy. They spend the night. Not long after, Alexis moves into his barren high-rise apartment. ”There is no furniture,” the boy observes. ”There is a table, two chairs, a mattress,” said Fernando. ”What else does one need?” A television and a boom box, Alexis explains. But soon the boom box goes over the edge of the balcony; Fernando is maddened by the music, as he is also annoyed by the ceaseless drumming of a neighbor, and by the musical tastes of a taxi driver who will not turn down the radio.

Alexis, a gang member who is always armed, helpfully kills both the neighbor and the taxi driver. Fernando is appalled and yet detached; the events in this city do not fully register–he is preoccupied by an inner agenda.

”Our Lady of the Assassins,” based on an autobiographical novel by the Colombian writer Fernando Vallejo, resonates also with Barbet Schroeder’s own life; he was raised in Colombia, has worked mostly in the United States and France, and at 60 is an extraordinary figure. ”No other person in the film world can match his record of diversity,” notes Stanley Kauffmann in his New Republic review. Schroeder’s interests are astonishingly wide. He produces all the films of Eric Rohmer, whose work could not be more different than his own, and he has made movies about Charles Bukowski (”Barfly”), the accused wife-killer Claus von Bulow (”Reversal of Fortune”) and ”Idi Amin Dada,” a doc about the dictator.

He made this Spanish-language film on the independent fringe, shooting on high-def video without permits, using guerrilla snatch-and-run video techniques, protected by bodyguards. Despite the danger involved in its production, the violence that weaves through all of its moments, and the documentary feel of the location photography in Medellin (”a city entirely without tourists,” Schroeder notes), ”Our Lady of the Assassins” is not a grim exercise in social realism. Fernando’s detachment sets the tone. He cannot easily be shocked or dismayed, because he’s on the way out of life. He is saddened by the death of Alexis (the two are grow genuinely close to each other), but that does not prevent him from finding another teenage lover, Wilmar (Juan David Restrepo). And when he discovers that Wilmar was Alexis’ killer–well, Alexis killed Wilmar’s brother, and what goes around comes around.

Can a man of 60 have a romantic relationship with a boy of 16? In a sane world, no. They would drive each other crazy. In a world where both expect to die in the immediate future, where plans are meaningless, where poverty of body and soul has left them starving in different ways, there is something to be said for sex, wine, music, and killing time in safety. And there is an agelessness in Fernando, who has no family, no plans, no bourgeois preoccupations, and has simplified his life to a zen emptiness–he and these boys share the same cool disinterest in tomorrow.

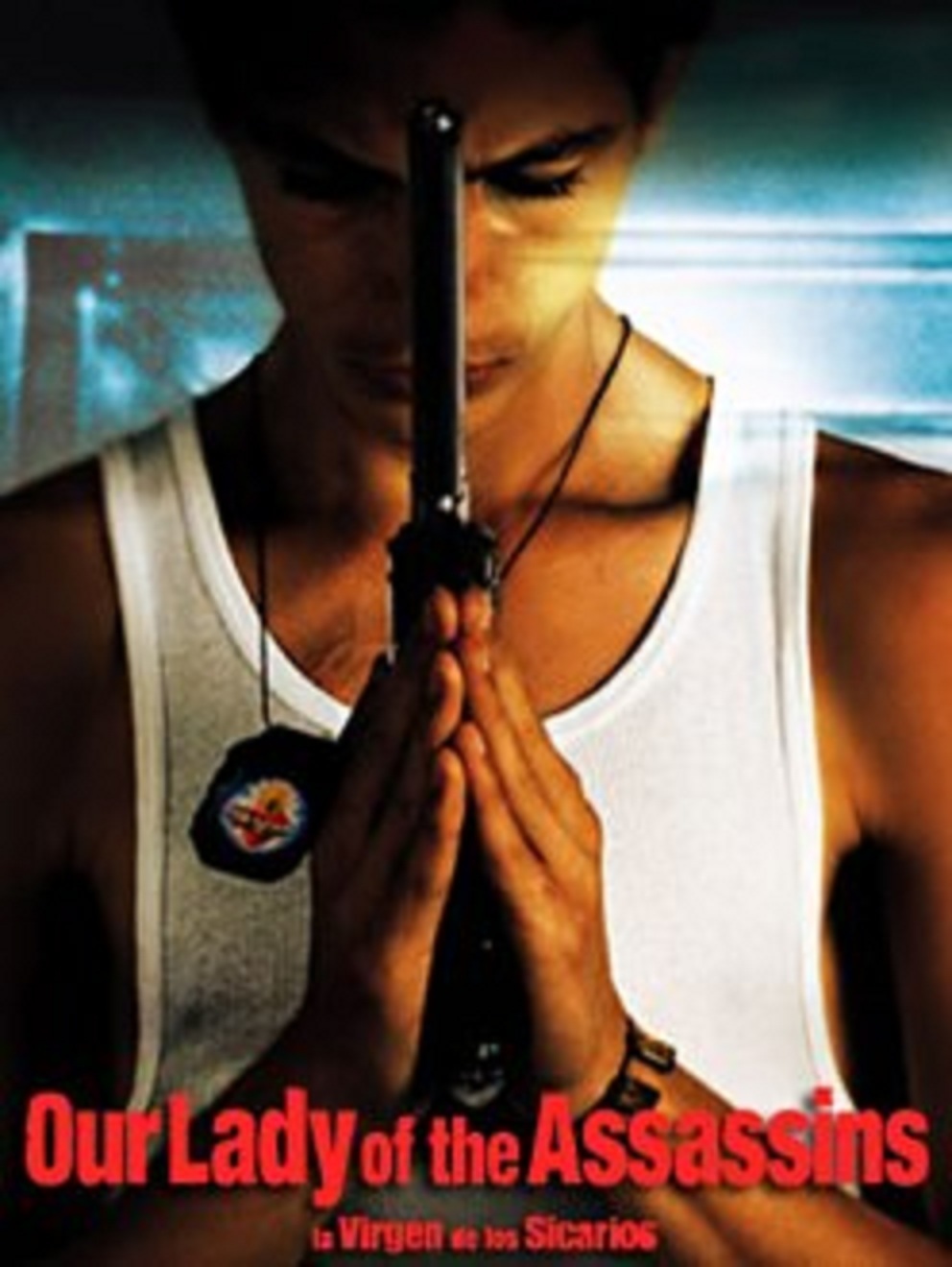

The morality of their arrangement of course is irrelevant in a city with no morality. (Every time a shipment of cocaine reaches the United States, the drug lords treat the people to a fireworks display.) The film’s title is appropriate. A desperate Catholicism flavors the doomed city. ”He’s happy it’s Our Lady’s Day or I would have killed him,” Alexis serenely observes after one violent episode. Drug deals take place in the cathedrals, and beggars fall on their knees to receive bakery handouts as if they are the eucharist. Cocaine has brought billions to Colombia but little of it has tricked down; unlike a boom town during the Gold Rush, Medellin does not share in the prosperity of its rich, but inherits only their depravity. A sign on a waste ground warns: ”No dumping of corpses.”