Ophelia is a tragic figure in a tragic play. First loved, then spurned by Hamlet, she goes mad and drowns in the river, though we do not know whether by accident or intention. In the play, Hamlet’s mother Gertrude describes Ophelia’s death as though she saw it herself, the girl “incapable of her own distress,” singing in the water “Till that her garments, heavy with their drink/Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay/To muddy death.” The image of the doomed girl was popular with the pre-Raphaelite, most notably the painting by John Millais, showing her lovely but bedraggled in the water.

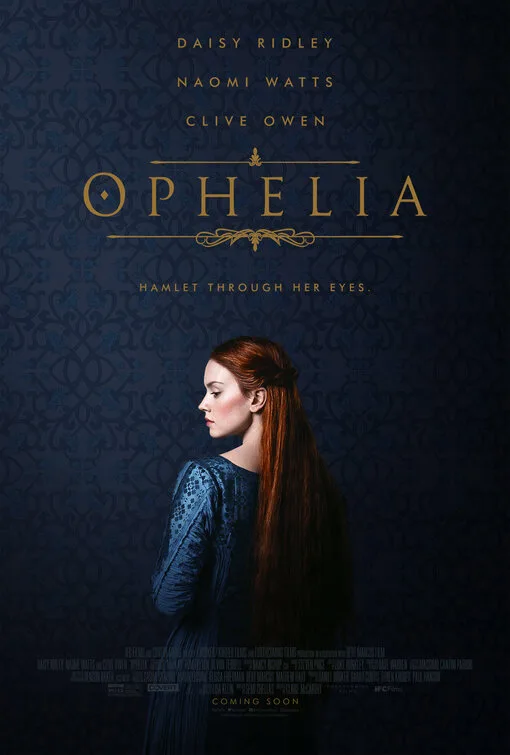

That is how Claire McCarthy’s “Ophelia” begins, the girl drowned in the river. But in this version, adapted by Semi Chellas (“American Woman” and the upcoming reboot of “Charlie’s Angels”) from a novel by Lisa Klein, we hear from Ophelia herself that this time we are going to see her side of the story. In this version, she is not the helpless girl driven to madness and likely suicide by a lover’s rejection. Played by “Star Wars” heroine Daisy Ridley, she has courage, intelligence, integrity, and agency. In this story, neither she nor the Danish prince she loves waste time worrying about whether to be or not to be. She is fully alive in every moment and ready to act to protect herself or those she loves.

In Shakespeare’s plays, whether comedies, romances, or tragedies, characters constantly jab at each other verbally, flipping words like tiddlywinks, with multiple layers of meaning. An Elizabethan wit could take a word, toss it up into the air and make it do a triple gainer on the way back down. “Ophelia” is filled with clever wordplay matched by an equally clever perspective flip of one of the central texts of Western literature.

As a young girl Ophelia is first mistaken for a boy because her widowed father Polonius (Dominic Mafham) is not able to give her the care she needs. When she speaks up fearlessly to Gertrude (Naomi Watts), turning the queen’s “alas” into “a lass,” she is taken on as a lady in waiting, washed, corseted, and taught the rules of courtly behavior. But she never loses her independent spirit, which makes her a favorite of the queen – at first. When Hamlet returns to find that his father is dead and his uncle has claimed the throne, she becomes a threat, especially when she and Hamlet are aligned. As in Shakespeare’s plays, wit here is more than jokes; it is a sign of an independence of thinking, a willingness to speak truth, even to power, even at great risk. It is also an ability to strategize and undermine that may be more powerful, even, than a witch’s potion.

There are parallels, and mirrored dualities throughout, and it is not only Ophelia whose character is made more vivid and complex. Scholars are still arguing about what Shakespeare’s Gertrude knew and how complicit she was in the murder of her husband before she married his brother. Here we see Gertrude as lonely and vain, trying desperately to hold on to her youth, whether through a witch’s potion or the attention of her husband’s brother Claudius (Clive Owen). Watts also plays another character, whose story intersects and echoes her own. Hamlet himself (George McKay) is in this version more direct and assured. Claudius is even more duplicitous.

Ridley brings the same verve and sincerity to Ophelia that she does to Rey in “Star Wars,” and Watts shows us Gertrude’s desperation and vanity. The story is made more vivid through with settings and costumes that are grand and beautiful but very much in service to the story, sound design that literally echoes the cavernous chill of the castle contrasted with the warmth of the natural world outdoors, and dynamic camera work to underscore the shifting points of view.

In 1966, Tom Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead” presented “Hamlet” from the perspective of two minor characters who die early and offstage. It was revolutionary in concept, remixing the themes of power, revenge, and agency in a classic by focusing on minor figures, with themes of powerlessness and stasis. These characters barely understood what was happening around them and were killed off only to prevent them from carrying out orders to kill the title character. It was not the first remix of a classic but a significant work in conversation with “Hamlet” (and with other works, like “Waiting for Godot”) and was likely in part an inspiration for other attempts to tell established stories from the perspective of minor characters, from “A Chorus Line” to “The Lion King 1 ½” (which is surprisingly good).

And now we have “Ophelia,” the story of the doomed Prince of Denmark, or rather, in this version, it is her story, and it is Hamlet who is the supporting character. And supporting he is, the famous imprecation “Get thee to a nunnery,” usually presented as contemptuous in the original, here is an effort to keep Ophelia safe from the treachery of the castle, part of a mutually agreed upon plan that owes something to “Romeo and Juliet” as well as its original source. This is one of many well-known lines of dialogue that take on new meanings here, as additional characters and scenes blend in so believably we can imagine them going on in rooms adjacent to the action we all remember. We see Hamlet bring in performers to reenact the murder of his father and the production here is a genuine work of art so eye-catching we may lose sight (literally) of its purpose, to catch the reactions of Claudius and Gertrude. Just as that play catches the conscience of the king, the richness of Shakespeare’s original provides the basis for a vividly imagined adjunct that provides additional insight into the classic and to our own ability to use art to illuminate the modern world.